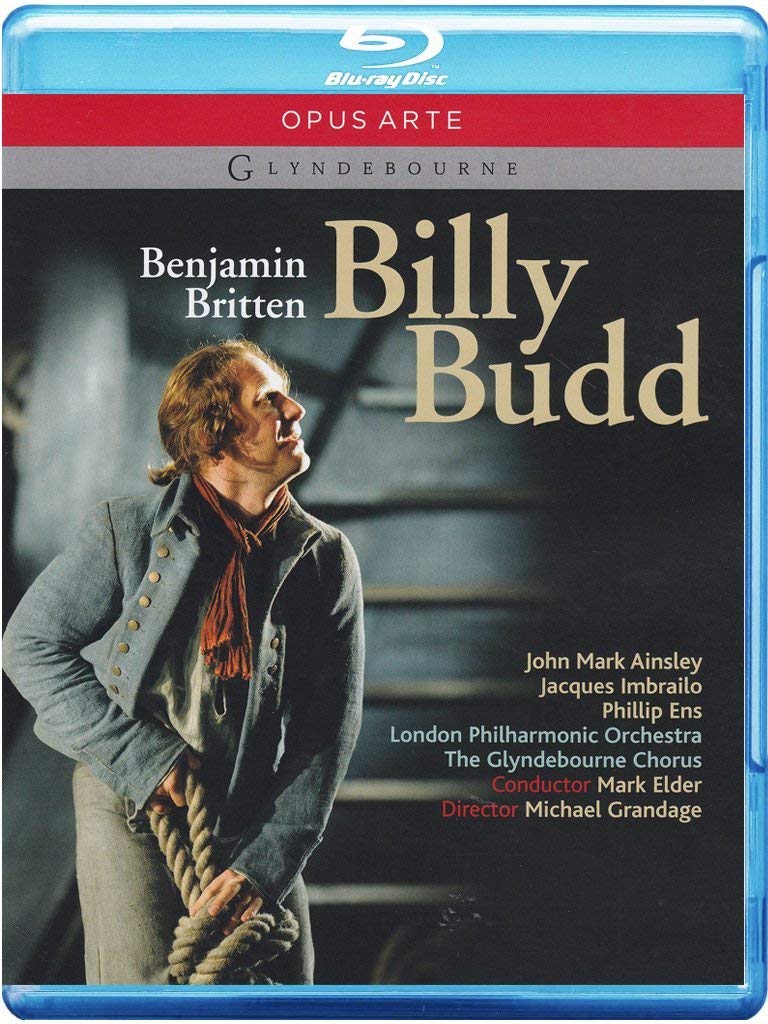

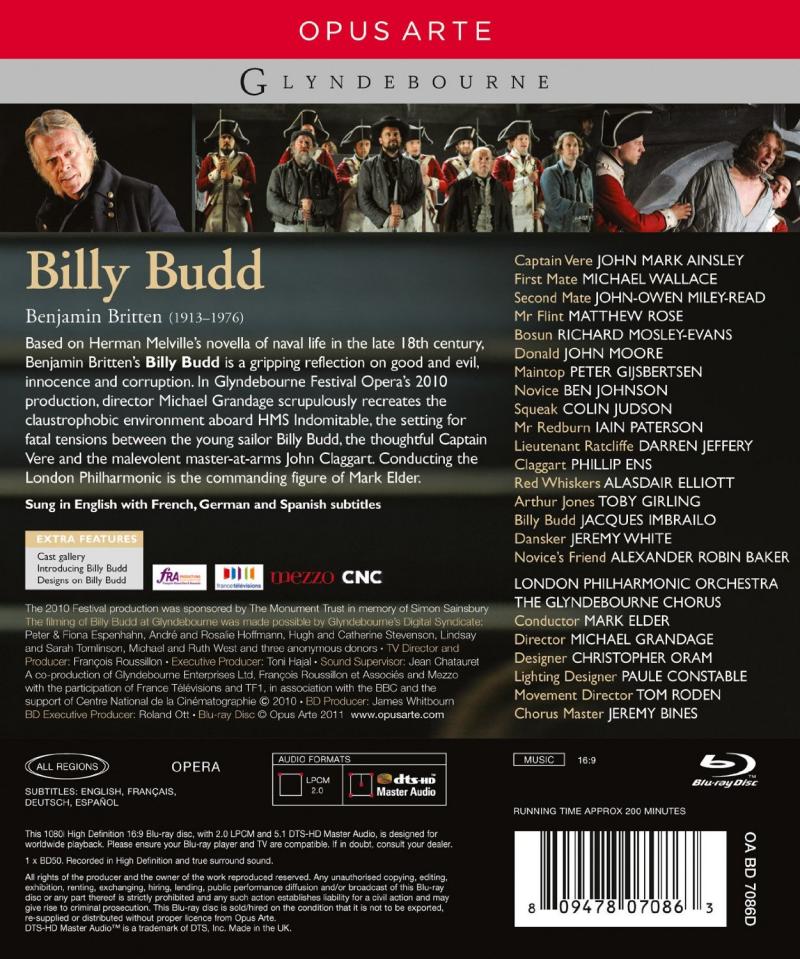

Benjamin Britten Billy Budd opera to a libretto by E. M. Forster and Eric Crozier. Directed 2010 by Michael Grandage at Glyndebourne. Stars (in order of apperance) John Mark Ainsley (Captain Vere), Michael Wallace (First Mate), John-Owen Miley-Read (Second Mate), Matthew Rose (Mr. Flint), Richard Mosley-Evans (Bosun), John Moore (Donald), Peter Gijsbertsen (Maintop), Ben Johnson (Novice), Colin Judson (Squeak), Iain Paterson (Mr. Redburn), Darren Jeffrey (Lieutenant Ratcliffe), Phillip Ens (Claggart), Alasdair Elliott (Red Whiskers), Tony Girling (Arthur Jones), Jacques Imbrailo (Billy Budd), Alexander Robin Baker (Novice's Friend), Jeremy White (Dansker), Sam Honeywood (Cabin Boy), Freddie Benedict, Alastair Dixon, Adam Lord, and Joseph Wakeling (all Midshipmen). Mark Elder conducts the London Philharmonic Orchestra (with Leader Pieter Schoeman) and the Glyndebourne Chorus (with Chorus Master Jeremy Bines). Set design by Christopher Oram; lighting by Paule Constable; movement direction by Tom Roden; sound supervision by Jean Chatauret. Directed for TV by François Roussillon; Executive Producer was Toni Hajal. Sung in English. Released 2011, disc has 5.1 dts-HD Master Audio sound. Grade: A+

The libretto is based on a Herman Melville novella, apparently inspired by actual events. It's a tragic story about Budd, an enthusiastic but misunderstood seaman, Claggart, the ship's chief of police, and Captain Vere, a decent but weak man who makes a mistake he can never live down. The story seethes with conflict among the main characters and the large crew, trapped together on high seas in time of war (no females roles).

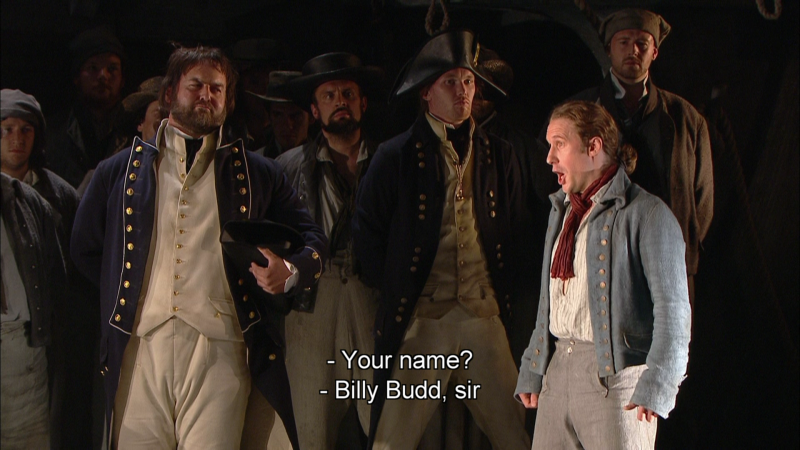

Billy Bud is impressed (kidnapped) from another ship. He is surprisingly enthusiastic as he sees this as a chance for advancement:

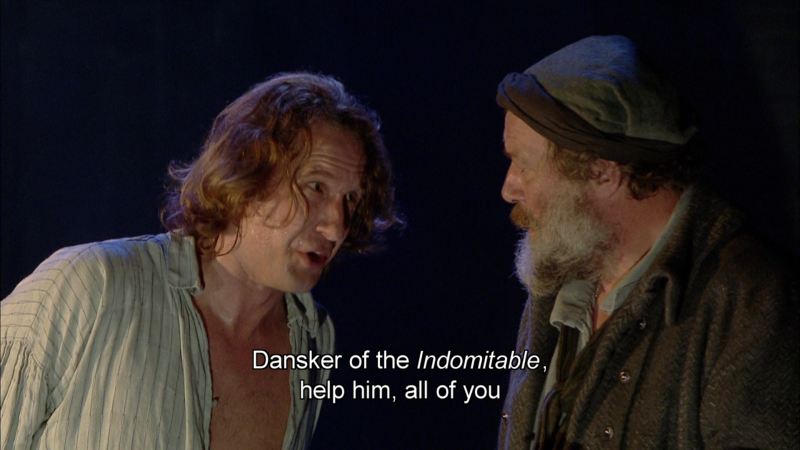

But Dansker, the oldest and wisest sailor, sees trouble ahead for Billy :

Meet Captain Vere, whose nickname with the men is "Starry":

Claggart, the Master at Arms, is detested as an evil man by everybody on the ship. Because evil hates the good, Claggart determines to destroy Billy (as old Dansker feared right away). Claggart's rationalization for this is that anyone so good a Billy may well be an enemy agent set on winning the sympathy of the crew and then starting a mutiny:

But this is a high-stakes game for Claggart!

A close-up the death of Claggart:

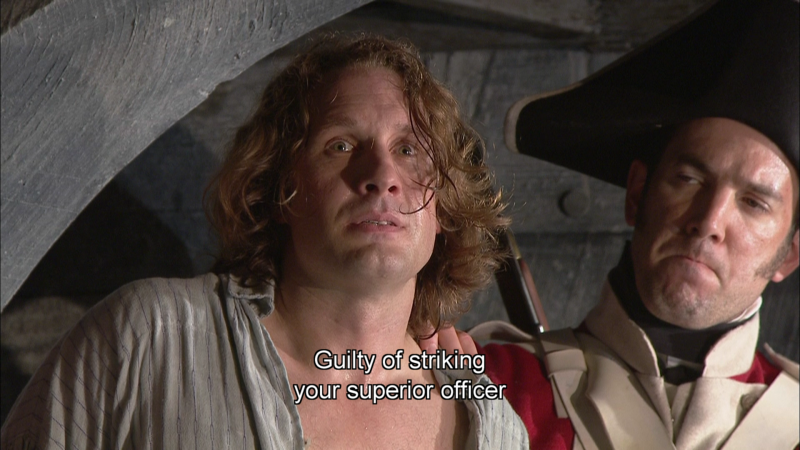

Billy has rid the ship of Claggart by striking him down. But this is a capital crime in military law, so what is Vere to do?

Tension mounts on the ship when Billy is sentenced to be hanged for killing Claggart. The eve before his death, Billy learns that a mutiny might in fact arise. But Billy absolves Vere of responsibility, and asks the crew to support their captain rather than mutiny. Vere will agonize over the death of Budd for the rest of his life:

The First Mate pronounces the sentence of death by hanging from the yardarm and the execution takes place immediately with Billy's best friends holding the rope:

Renowned theater director Michael Grandage made his opera debut with this production. Somewhat surprisingly, considering that the composer was British, this was the opera’s first performance at Glyndebourne (it premiered at Covent Garden in 1951). In one of the two fascinating “Making of” bonus features, Grandage states that “I’m not the kind of director who enjoys immediately looking at a time and a place set by a writer, and then going ‘Let’s not do that.’ It gives me more pleasure to try and interpret something that was clear for them when they first set about writing it and trying to bring that clarity to a new production.” That sounds promising, but does it mean that we get a production that actually follows the libretto’s specification that the setting is “On board the HMS Indomitable, a British man-of-war, during the French wars of 1797”? The answer is a resounding “yes” – no arbitrary updating to a different era, no anachronistic costumes or set decoration, and no Eurotrash of any sort. What a concept – adhering to the express wishes of the opera’s creators!

Preliminary work on this production began 2½ years before it opened. The company had the luxury of 5 weeks of rehearsal time – and it shows. This is a finely honed performance, with every singer seemingly at the top of his game. Especially notable are Jacques Imbrailo as Billy and Phillip Ens as Claggart. The London Philharmonic Orchestra, with Sir Mark Elder conducting, gives a virtuoso performance. The lighting is done in such a naturalistic way that one could almost fail to notice its perfection.

There is a wide variety of scenes, from soliloquies to the entire cast occupying the three levels of the set and completely filling the stage view from bottom to top. There is not a single moment in 2¾ hours in which any performer seems out of character (at least as captured by this video). The acting by the principals in particular is amazingly convincing, and there are plenty of close-ups to confirm this observation.

The audio was recorded with a wide dynamic range and frequency response. The balance between the vocals and the orchestra seems well-nigh ideal, with neither ever dominating the other. The sound of the orchestra is enormously impressive, with tremendous impact on the low end, natural sheen in the highs, and a solid mid-range. This is a sound that virtually puts the listener in the best seat in the house. By the way, despite the fact that the libretto is in English, most listeners will find it desirable to watch with the subtitles engaged.

The video production is impressive, although it could have been even better with fewer cuts. There’s no point at which the editing could be described as frenetic, but occasionally one wishes a certain view would be held for a few seconds longer. Video director François Roussillon had a locked-down camera dedicated to a view of the full width and height of the stage. He uses it often to give an unbeatable perspective, especially when the full cast is in action. A notable example of this is at 1:37:08 (in Chapter 21), with the full-stage view held for 30 seconds:

This shot is followed immediately by a near-range shot of Captain Vere and two of his officers that is held for 20 seconds. While these choices represent the exception rather than the rule in the editing of this production, they demonstrate that Roussillon was trying to enhance the home-theater experience by taking full advantage of HD video:

Perhaps the most remarkable shot in the entire production begins at 1:49:27 (during the transition from Scene 1 to Scene 2 of Act II) as we view part of the orchestra in the pit from the left side (the back rows of players are unavoidably obscured by the stage overhang}. Other than a few seconds at the opening of Act II, this is the only view we get of the orchestra and conductor in action, but we are rewarded with a very gradual zoom toward the conductor in a shot that lasts 1 minute and 28 seconds! During this entire time we have the opportunity to see Sir Mark Elder conducting stunningly complex and exciting music:

The previously referenced bonus features include interviews with Grandage, Elder, and several principal cast members, along with those in charge of lighting and stage design. These features are a valuable enhancement to the viewer’s understanding of this opera and appreciation for the labor of love that this production represents.

I would have preferred 96kHz/24-bit audio for this admirable show with its gripping modern music. But still, the great performance and nearly impeccable video inspires me to give this title the grade of "A+."

This review was contributed by Wonk Gordon Smith with screenshots provided by Hank McFadyen.

OR