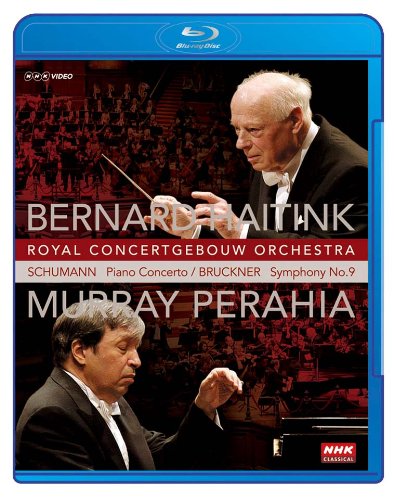

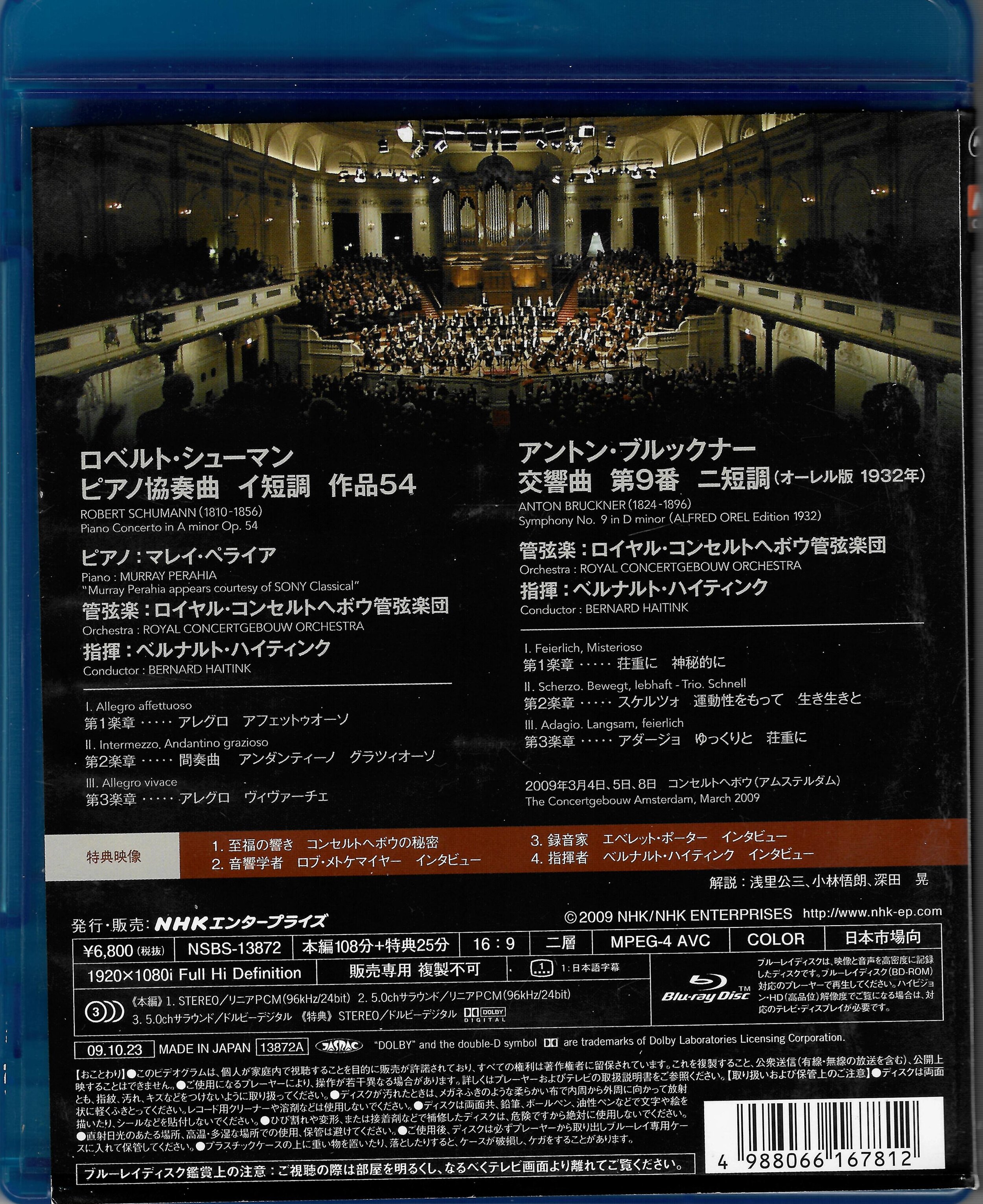

💓 Bruckner Symphony No. 9 and Schumann Piano Concerto. Bernard Haitink conducts the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra in 2009. Murray Perahia is the piano soloist. The title is the first effort by NHK to produce an HDVD of Western classical music with performers who have no special connection to Japan. The front cover is in English. But the rest of the disc is in Japanese. There are extras with persons speaking in English, but only Japanese subtitles are provided. So this disc is not aimed at the world market, but just for domestic consumption in Japan. Released 2009, the sound on the title was recorded with 96kHz/24-bit sound sampling, and the disc has 5.0 LPCM output. Grade: A+ for both the Schumann Piano Concerto and the Bruckner Symphony No. 9.

Gramophone magazine in 2011 ranked the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra as the best in the world. Haitink was long the conductor there before he was succeeded by Mariss Jansons. Haitink was invited back as guest conductor, so this was a sentimental event for everybody. The Gebouw itself also seemed to enjoy the evening by emitting its own mysterious aura. It's the most magnificent music venue I've seen. It has the same "shoebox" shape as the Vienna Großer Musikvereinssaal (the “Golden Hall”). But it is larger and grander even than the Vienna hall and appears consecrated, as if it were a church. It features staircases that emerge from the top of the back wall and fall sweeping past the huge organ through the performing stage to the conductor's podium. When the conductor and soloists descend these steps, you think of Judgement Day.

Next belaw are comments from Wonk William Huang about this title. After that I (Hank McFadyen) have provided screenshots and "statistics." Finally, don't overlook a valuable comment below by Wonk James Kreh.

William Huang:

“Whenever a new musician or ensemble gains significant recognition in the classical music world, eventually there is a recording contract. But, alas, the contract usually only shows how uncreative record companies are in producing a stream of recordings—of Bach's violin concertos, Liszt's Piano Sonata, or another cycle by Brahms or Mahler, etc,—all with the same lacquered, homogenized sound.

Another sector within the recording industry is even more frustrating and tepid—video production. Concerts are seldom filmed well (watch any of the Berlin Philharmonic's annual “European Concert” series) and often have little more music than an LP. Archival footage is released at a trickle, with companies mostly re-releasing the same film, format after format. The greatest rarities are well-designed films of great performances made in the present. Considering how the industry treated laser-disc, VHS tapes, and DVD, it's no surprise that they've also used Blu-ray technology as just another profit center.

To be sure, Blu-ray videos are indisputably clearer than any concert DVD available. In a typical classical music Blu-ray, one can see almost every single audience member within a frame and sweat dripping off the musicians. The video is so clear you can sometimes read the score. Even with a good seat at a concert hall, it's almost impossible to see most of these details. Still, until now, no Blu-ray made a convincing case that it was a real step up from DVD.

Then came our review disc from NHK Classical, a Blu-ray featuring the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, Bernard Haitink, and Murray Perahia. Its release for the Japanese market probably restricted awareness in the West, which is sad. For there has never before been a recording of classical music that so thoroughly captures the magic of live orchestral music! The concert features Schumann's Piano Concerto and Bruckner's Ninth Symphony, well-known specialties of Messrs. Perahia and Haitink. The synthesis of the Concertgebouw Orchestra's otherworldly performance and NHK-Classical's conscientious production is not just a concert film with a sharper visual than DVD. It is a portal to another world!

As produced by the careful hands of NHK-Classical, Blu-ray is the best format yet for the presentation of classical music. The roughly two-hour-long soundtrack on this single disc holds five times as much data as a commercial CD. Using eighteen microphones and Blu-ray’s larger storage capacity, NHK-Classical was able to meticulously record this concert at 96 kHz/24-bit. A Blu-ray disc miked as well as this one can capture one or one hundred acoustic instruments with abundant details and resonance. Thus virtually every harmonic line or note that Bruckner or Schumann wrote can be heard on this disc.

Complementing the disc's audio, NHK-Classical also made spectacular use of Blu-ray's high-resolution video to show how the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra performs. This is often achieved with stylish long-range shots of the whole ensemble or large sections. Even these long-rang shots are so clear that no musician looks minuscule or distorted. Like sitting in a good terrace seat, such angles give the viewer the freedom to see at whoever is playing—no matter how far apart—and make a judgment on what to pay attention to.

It's a joy in the Shumann concerto to see the concentration and poise of Murray Perahia and to hear the fluidity and nuances of his playing. Listeners might prefer a more brisk tempo in the fashion of Sviatoslav Richter or Martha Argerich, but it is obvious to me that Perahia's regal tempo is an artistic choice rather than a physical compromise. His crystalline finger work is marvelous, and the tempi are never lethargic or hurried. When I hear Perahia play Schumann, I hear the composer speak. When I hear Martha Argerich perform the same concerto, I hear her. Perahia's performance, the scenic camera angles, and the rich, layered sound make me think of Clara Schumann's observation of her husband's concerto "[… ] it must give the greatest pleasure to those who hear it. The piano is most skillfully interwoven with the orchestra--it is impossible to think of one without the other."

Haitink, a Bruckner expert, leads a noble and dedicated performance of the Master's Ninth. It’s almost surprising how his gentle, grandfatherly stage-presence inspires such concentration and intensity from the Dutch players. Rather than making an overly dramatic reading, the conductor lets the music speak for itself. The scherzo has a fiery brilliance. It's thrilling to hear the effortless legato playing of the woodwind players and the rich unisons of the strings. The outer movements are spacious and deeply expressive. And Bruckner's awe-inspiring orchestral tuttis make the Concertgebouw orchestra a force to behold.

This is the most impressive recording of classical music yet produced in the twenty-first century. "

Schumann Piano Concerto

Now for some screenshots, all with fine resolution and color balance. First, here's a full-orchestra view of the piano concerto:

Let's get a bit closer:

And here's a keyboard shot. Have you ever noticed the optical illusion where the keys on the far side of the pianist appear to be longer than the keys on the near side? You don't see that here because the camera has enough depth of field of focus to keep the entire keyboard looking like it's supposed to:

But the players behind Perahia in this shot are outside the field of focus. This is considered OK because it keeps the viewer's attention on the star player:

Haitink looks avuncular in this cozy shot:

This is a good angle for showing the concert master (too often we see the back of the right ear of the concert master):

The cello section (5 of 6 players):

Here is a new Wonk Worksheet with the numbers on the Schumann concerto. The video starts with good whole-orchestra views to help you get oriented to where the musicians are seated. The average video clip lasts 13.5 seconds, which is more than twice as stately as the average DVD with 5 seconds per clip. Only about 16% of the clips show the conductor, which is good. And the "supershots", which take full advantage of HDVD resolution, make up an excellent 61% of the total number of clips. So this video passes all our tests for the good symphony HDVD. There is some panning and zooming, but the moves are slow and tasteful. All this in support of Perahia's superb performance results in an A+ grade.

Bruckner Symphony No. 9

The orchestra for the Bruckner symphony is a magnificent thing to see:

This view is as close as you can get and still see all the winds:

The next angle below lets the TV Director focus on the lower strings:

Here's a great shot of all the winds (except for 3 horns):

Below are half the horn players working out on Wagner tubas:

There was no camera on the stage to the left of the conductor. This means there was no way to get a great shot of all the violins. Well, here's a view of some of the 1st violins:

And here's a beautiful shot of 2nd violins and violas:

Finally, here's a pensive Haitink portrait:

Here is a new Wonk Worksheet with the numbers on the symphony: The average video clip lasts 13.7 seconds, which is close to 3 times more stately than the average DVD with 5 seconds per clip. About 20% of the clips show the conductor. And the "supershots", which take full advantage of HDVD resolution, make up about 30% of the total number of clips. Many of the part-orchestra and whole-orchestra shots last much longer than 13.5 seconds. So the supershots run for substantially more than 30% of total playing time. There is some panning and zooming, but the moves are slow and tasteful. The only problem noted with the video would be some focus problems with a camera shooting horns from the side. All this, together with the magnificent performance, earns another A+.

This Blu-ray HDVD received in 2012 an award in Japan from the Digital Entertainment Group for its sound recording. The DEG citation called this the "best [sound] recording ever released on music video."

Sum up: This is a beautiful HDVD of a special event played by great musicians in one of the world's top concert halls. The disc demonstrates convincingly that recording with 96kHz/24 bit specs can produce better sound than what we have known before. And because this title was recorded primarily to be shown on HDVD, the video content is superior to most of the other HDVDs of classical music I have seen. This disc (and a few others mostly from NHK) now provide us with a model against which all other classical music HDVDs may be judged. In addition to the A+ grade for both pieces, this title gets a 💓 award for special merit and significance.

A comment from James Kreh:

After enduring multiple hours of a Beethoven Symphonies 1-9 set severely infected with DVDitis, I had to experience the Bruckner on this Blu-ray as a palette cleanser. This video really is the gold standard for symphonic recordings on HDVD, and is very much worth the premium price.

I’ve enjoyed Bernard Haitink’s recordings for decades, especially his Bruckner. A New York Times review of October 2013 concerts with the London Symphony Orchestra referred to Haitink’s “studied naturalness”, which I think perfectly describes this conductor’s musical approach.

The booklet and on-screen titles note that the recording on this disc was made in March 2009. Perusal of the fine print in the booklet (with Arabic and Japanese numerals mixed together) discloses specifically that this was taken from concerts on March 4, 5, and 8, 2009. It happens that the conductor was born on March 4, 1929, so obviously this series of concerts constituted a celebration of Haitink’s 80th birthday with the orchestra with which he shared the core of his career. (There’s surely a discussion of this in the booklet, but I can’t quote or cite it because the text is in Japanese.)

There have been many conductors famous for “slowing down” in their later years (i.e., taking slower tempos), with Klemperer perhaps being the prime example of this phenomenon. This does not seem to be the case with Haitink. This can be discerned (at least for the Bruckner 9th) from comparing the timings of the three movements on this recording with those of the two studio recordings he made with the Concertgebouw:

1965: 23:15 | 11:15 | 24:52 (recorded when Haitink was only 36, this is a young man’s Bruckner)

1981: 25:11 | 10:51 | 26:28 (recorded in his prime at 52, toward the end of his 1961-1988 tenure as principal conductor)

2009: 25:32 | 10:40 | 26:25 (almost identical to 1981, with this scherzo being the fastest of all!)

I should note that the Schumann Piano Concerto is also a wonderful performance, but it’s the Bruckner that keeps me coming back to this fabulous HDVD.