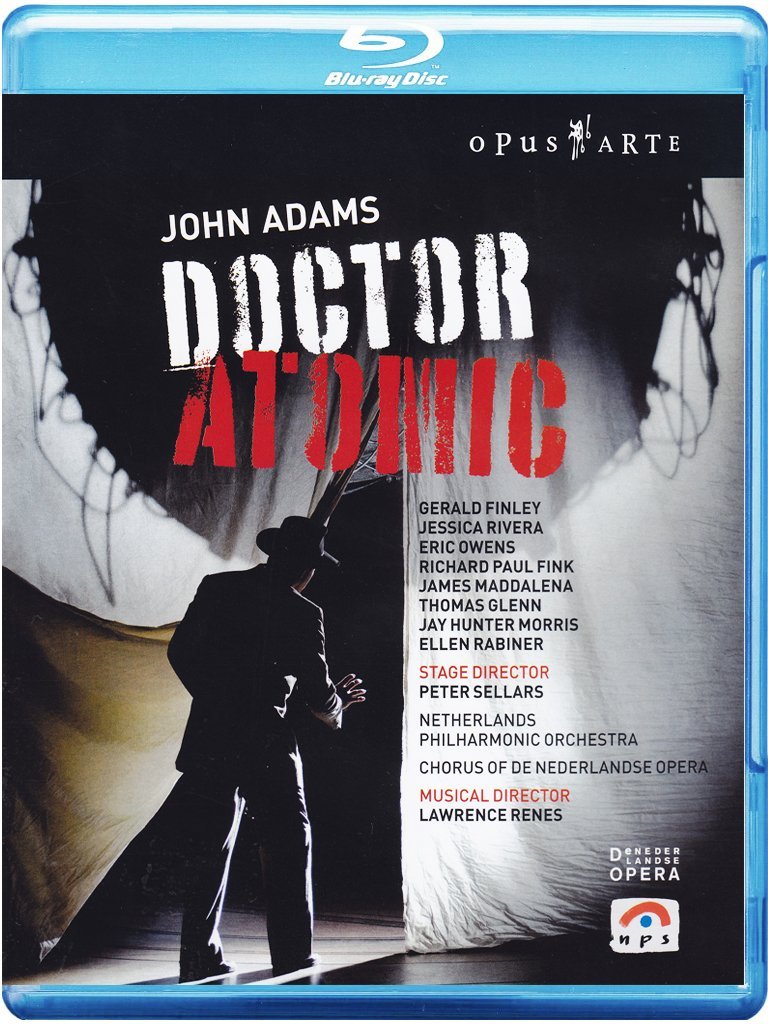

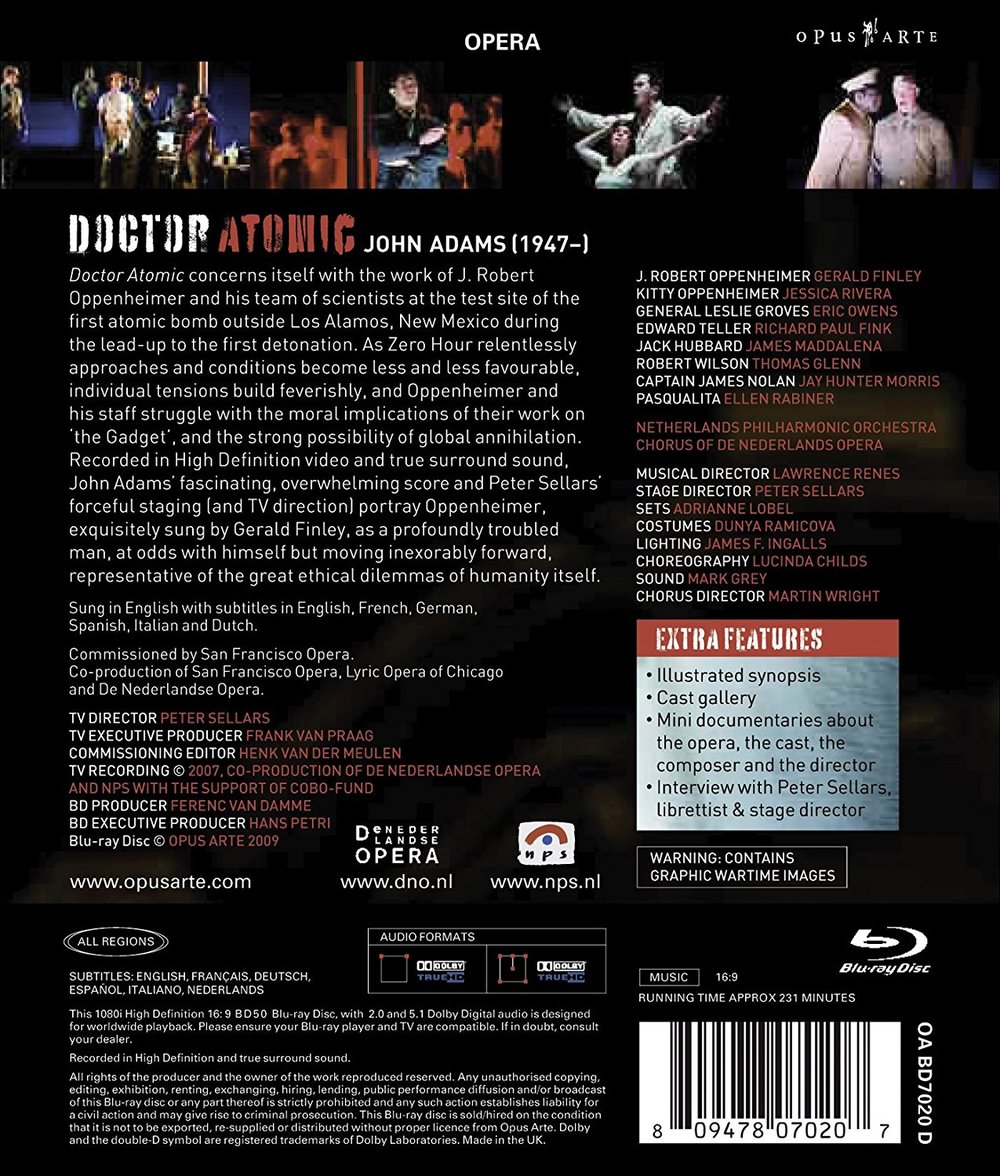

John Adams Doctor Atomic opera to libretto of historically accurate statements and a clutch of poems assembled by Peter Sellars. Directed 2007 by Peter Sellars at De Nederlandse Opera. Stars Gerald Finley (J. Robert Oppenheimer), Jessica Rivera (Kitty Oppenheimer), Eric Owens (General Leslie Groves), Richard Paul Fink (Edward Teller), James Maddalena (Jack Hubbard), Thomas Glenn (Robert Wilson), Jay Hunter Morris (Captain James Nolan), Ellen Rabiner (Pasqualita), and Ruud van Jijk (Lieutenant Bush). Lawrence Renes conducts the Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra and the Chorus of De Nederlandse Opera (Chorus Director Martin Wright). Sets by Adrianne Lobel; costumes by Dunya Ramicova; lighting by James F. Ingalls; choreography by Lucinda Childs; sound effects by Mark Grey. Directed for TV by Peter Sellars. Sung in English. Released 2009, disc has Dolby 5.1 TrueHD sound. Grade: B

If you're new to a work, I usually suggest that you watch it cold. But Doctor Atomic is a profound opera, and it likely will seem difficult on first encounter. So watch the extras first. Start with the 27 minute interview with Peter Sellars. You probably already know that Doctor Atomic depicts the personalities and events surrounding the first atomic bomb explosion achieved by the Manhattan Project under Dr. Robert Oppenheimer on July 16, 1945. Sellars in his interview gives you backstory and discusses the moral issues that arose in 1945 and which still haunt us today. From the remaining extras you can get up to speed on the characters portrayed and see historic photos of some of the gear that is represented by props in the show. You can prep for the shifting style and tone of various segments of the libretto, which you can find on the Internet.

Right now it’s August 3, 2020. The first atomic bomb test took place on July 26, 1945, about 75 years ago. The first atomic bomb to be used in combat was dropped on August 6 over Hiroshima. It was a “Little Boy”, with the spherical shape depicted in the opera. (The Nagasaki bomb was the larger “Fat Man”.)

Doctor Atomic premiered in 2005 at the San Francisco Opera. The opera video, also directed by Peter Sellars, was made from the 2007 opera production in Amsterdam. Opera Base says there have been 13 productions of Doctor Atomic with 104 shows to date. Only 2 productions (16 shows) took place in the last 5 years. So it seems the opera has been, to use a military term, a dud, and it’s most unlikely you will ever have a chance to see this live. We will explore why in this review. But Sellers video is good enough, I think, to live on.

The opera depicts the roughly 24 hour period before the first test detonation at 5:30 am. The movie opens with a tiny physics lesson:

Lucinda Childs was still big back in 2007 and her dancers often dominated the stage in the theater. Sellars shrinks their role in the video, but they do get to shine it the demonstration below with dancers in the outer circle representing the Little Boy and dancers in the center squeezing the plutonium core of the weapon to “crack atoms” in the “implosion device”:

But, of course, the main subject of the opera is to explore the moral issues surrounding atomic weapons. The libretto does a good job, I think, of introducing you to how these issues were very much on the minds of the scientists working in the huge Manhattan Project. Many of the scientists came from European countries that had fallen under the control of Fascist leaders, including Jews fleeing Hitler. These men had various intellectual and political backgrounds, but they were unified by the fear that Hitler might develop the bomb first. The surrender of Germany just a few days before the opera opens had changed the picture completely. What should the Allies do with the new weapon (assuming it would actually work)? Below we see young physicist Robert Wilson working on a petition to send to President Truman urging him to try ending the war in the Pacific without actually using the bomb in combat:

Below left we see J. Robert Oppenheimer (Gerald Finley), lead scientist in the Manhattan Project, talking Robert Wilson (Thomas Glenn) out of causing trouble with a petition. Unstoppable forces would result in a surprise use of the weapon for maximum psychological effect on the Japanese:

Sellars also manages to give us a taste of the complicated relationship of Oppenheimer with Edward Teller (Richard Paul Fink), another leading physicist in the thick of things. Both were Jews who fled Europe for the United States. Oppenheimer was deemed essential for getting the atom-splitting, or implosion device, ready for use as a weapon (as “father” of the atomic bomb) even though Oppenheimer had demonstrated sympathy with Communist doctrine in the past. Teller is shown in the movie as a subordinate with an even greater and more visionary frame of view than Oppenheimer. Teller was both the father of the hydrogen, or fusion bomb, to come later and an early advocate for the theory of MAD, which seeks to keep the peace through “mutually assured destruction.” Perhaps the tension between Oppenheimer and Teller was controlled at the time by their own mini-MAD pact. Later this was to fall apart in a huge stink after the Cold War started. Oppenheimer’s loyalty was questioned and his security clearance was put under review. When Teller was asked to testify about Oppenheimer’s political reliability, Teller’s statement was so ambiguous that it was considered a betrayal by most of their mutual colleagues, and Oppenheimer security clearance was revoked. In the screenshot below, “Oppie” relates to Teller what he told General Marshall and others in Washington about the effect of an atomic attack on Japan:

The men in this story represent intellect and the will to survive. The women represent nature and the will to thrive. When the men are working on the bomb, the libretto uses ordinary sentences describing historical events. When the women get involved, we take a deep plunge into modern poetry almost as complicated and abstruse as the formulas used in nuclear physics. The libretto is like a deck with poker cards and tarot cards shuffled together. How did this come about? Before I tell you, let me illustrate this issue with a specific example.

The top dogs in the Manhattan Project were civilians and they had their families with them in special quarters. (The joke was that during the Project they produced bombs and babies.) As the time for the test approached, the technical control team took over the arming tasks, and Oppie had time to visit his family (200 miles away). Below you see Oppie in bed with his beautiful wife Kitty. Of course, he’s reading unfinished paperwork. Kitty thinks some loving should trump the office memos, and she sings to him word for word a 28 line poem called “Am I in your light?” from the American poet Muriel Rukeysayer. Once you have had time to study the text of the poem carefully, you see how the poem fits this situation well:

Oppie responds with 47 lines (in English) from the Baudelaire erotic poem “ A hemisphere in your hair” including the two lines you see in the next two screenshots below. Do you see what has happened? Before Oppie gets in bed with Kitty the opera is all standard poker cards. But now we have been hit with 2 tarot mysteries. Believe me, you likely will have no idea what to think of this unless you happen to have a Master Degree in modern English literature and a PhD in French letters. And trying to absorb all this from singers on an opera stage would probably be tough even for those with special background:

So where did this strange mixed deck of cards come from? Well, originally the composer Adams and the stage director Sellars hired Alice Goodman to write the libretto for Dr. Atomic. (These three were the team that created Nixon in China.) But Goodman pulled out of the project fairly late in the game. Apparently there was no time to find a new writer. So Sellars assembled a text from historical sources and poems that seemed to work well with the historical plot. It was a fact that Oppie admired Baudelaire. Sellars probably noted that a “hemisphere of hair” was an echo of the hemispheres of plutonium used in the Little Boy. Could it be that the bedroom scene above was imagined by Sellars after he came across the two poems in this research? Of course we will never know. But this much is certain. There are at least 23 substantial blocks of text with poetry from Rukeysayer, Baudelaire, John Donne, the Bhagavad Gita, and Tewa folksongs. These blocks make up about 30% of the total libretto. As soon as you run into anything weird, you know you are into poetry.

Most of the poetry is forbiddingly esoteric, but not all. Here are 9 lines from Rukeysayer that are readily comprehensible coming from Kitty: “Those who most long for peace/ now pour their lives on war. /Our conflicts carry/ creation and its guilt,/ these years’ great arms/ are full of death and flowers./ A world is to be fought for, sung, and built:/ Love must imagine the world:

Back now to the test site as the countdown to infinity continues. General Groves (Eric Owens), the military boss of the test range, is easy to understand:

Back at the test range, Oppie visits Little Boy one last time. I think you see the Fat Man in the background:

Finley became famous for his creation of this role and especially his rendition at the conclusion of Act 1 of an aria on the text of John Donne’s Holy Sonnet 14:

Now that the men in our story have done all they can, we turn out attention again to the women. Kitty has 2 kids and she has hired a Tewa Indian lady named Pasqualita (Ellen Rabiner) as a maid. Kitty is a prickly woman who has an alcohol problem. The maid is drinking milk. The women know something big is about to happen:

The lyrics to the Tewa folk music are easy to understand:

Baby sitters join the vigil and pretty soon everybody is drunk:

Sellars can’t resist any opportunity to display his erudition: now Thomas Mann gets in the act via Robert Wilson:

The countdown begins and the libretto turns to black humor and the private thoughts of observers:

The Little Boy was not going to be efficient since this was the first and somewhat crude attempt mechanically to create an uncontrolled nuclear chain reaction in a piece of plutonium. The big boy shots only succeeded in using less than 2% of the plutonium core, so it was actually a guess what the yield of the first test shot might be. Everybody joined in a betting pool. Many guessed quite low. Teller high. The actual yield was 13 kilotons and Stanislaw Ulam was the winner with a guess of 8:

More tarot card poetry from the Bhagavad Gita, but this poem was easy to understand:

Now Seller’s video starts to take on an hallucinatory cast:

A extreme close-up of Kitty:

Sellars made no effort to depict the atomic explosion directly. I think red sky below shows the “sunrise in the west” that was observed at the headquarters compound:

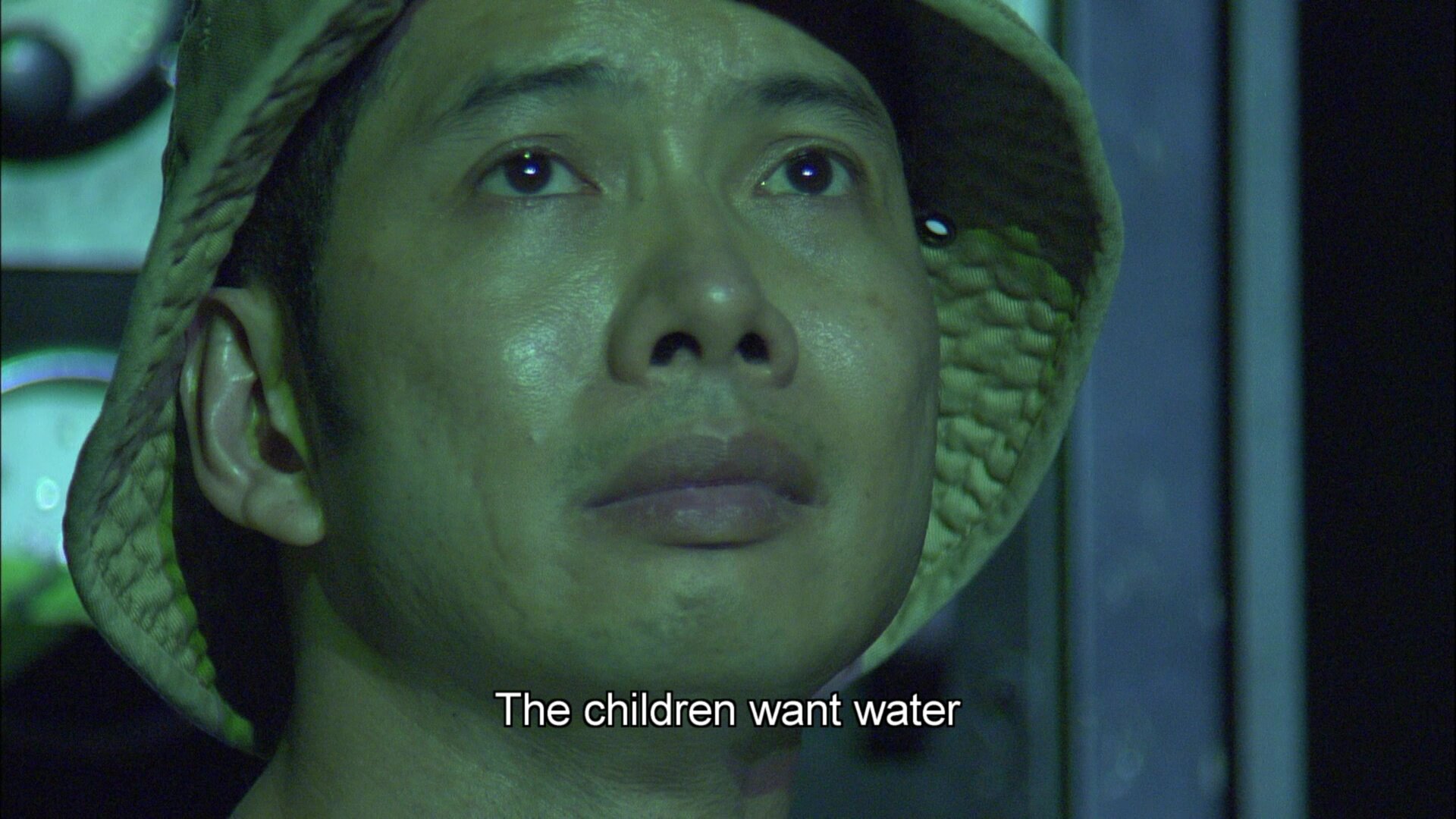

And the video ends, shortly after the real beginning of the atomic age, with the voice of a Japanese woman looking for her husband and children asking for water:

The Adams orchestral score doesn't sound particularly aggressive by the standards of today's music. The singers and chorus are all fine, especially Gerald Finley as Oppenheimer. SQ is good. Adams bestows little melody. It just happens that a new CD just came out with the compete music of the opera played by the BBC Orchestra conducted by John Adams himself, and this is being hawked as the definitive sound recording. Subject title is the only video.

The problem remains the missing libretto that should have been written by an author capable of expressing, in easy-to-comprehend prose or verse, the point of view of the women and their will to thrive. The opera is also too long at 2 hours and 50 minutes amplifying the plot outlined above in our screenshots. There is no dramatic tension because the audience knows what will happen. So excellence of execution is all that matters, and nothing is excellent about 50 minutes of sung text too complicated for the audience to comprehend. People who saw the live show were often bored.

In addition to assembling the pastiche libretto and directing the show, Sellars also took charge of making the video recording. The video is not an attempt to show an opera on the stage. Instead, Sellars shot a movie using the stage show as his location. He hoped to use the his movie to drum up interest in the live show. This failed, but strangely, the movie has proven to be better than the live opera. With all the near and close-up shots, it’s completely clear who is singing each line and what each line states. Where there is obscurity and tortured poetic imagery, the viewer in the home theater can stop the show, consult the written libretto, and try to figure things out.

If you have the video, you have a fighting chance. Each time I see this, I like it better. I have a daydream that Adams will hire a writer and come up with a revised version of that can be an engrossing live opera. Of course, this will never happen. Be content with the video, to which I’ll give a B. If you happen to know a lot about modern poetry, this would maybe be an A title.

Here's a decent clip of Finley singing of Oppenheimer's aria at the end of Act 1:

OR