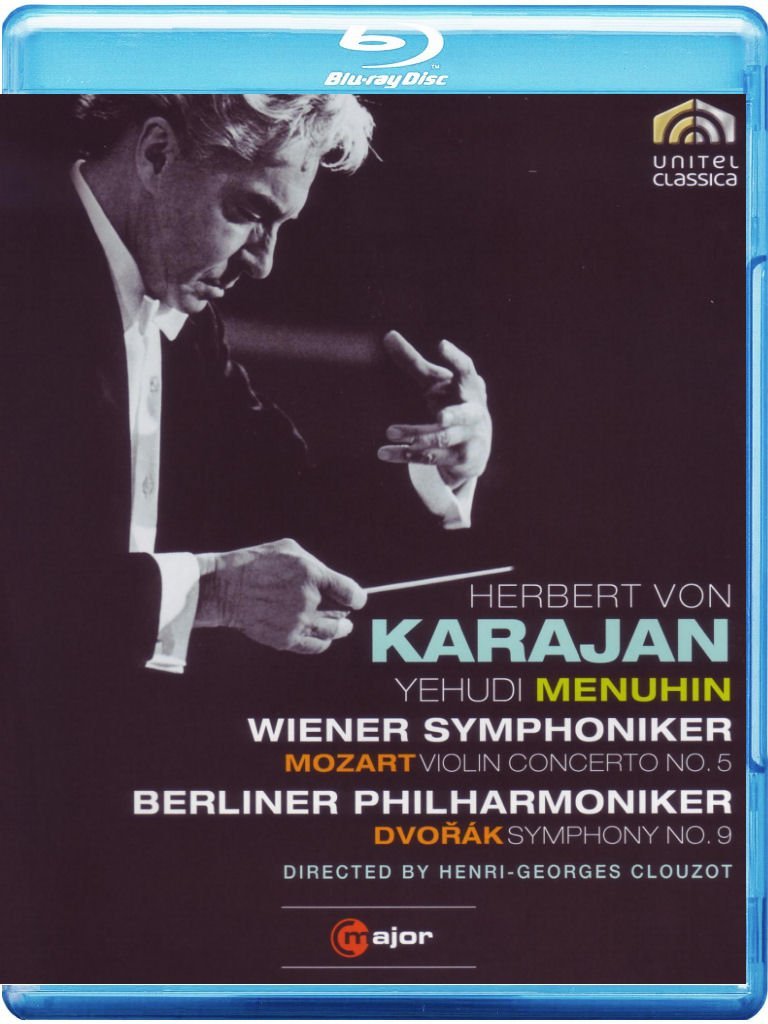

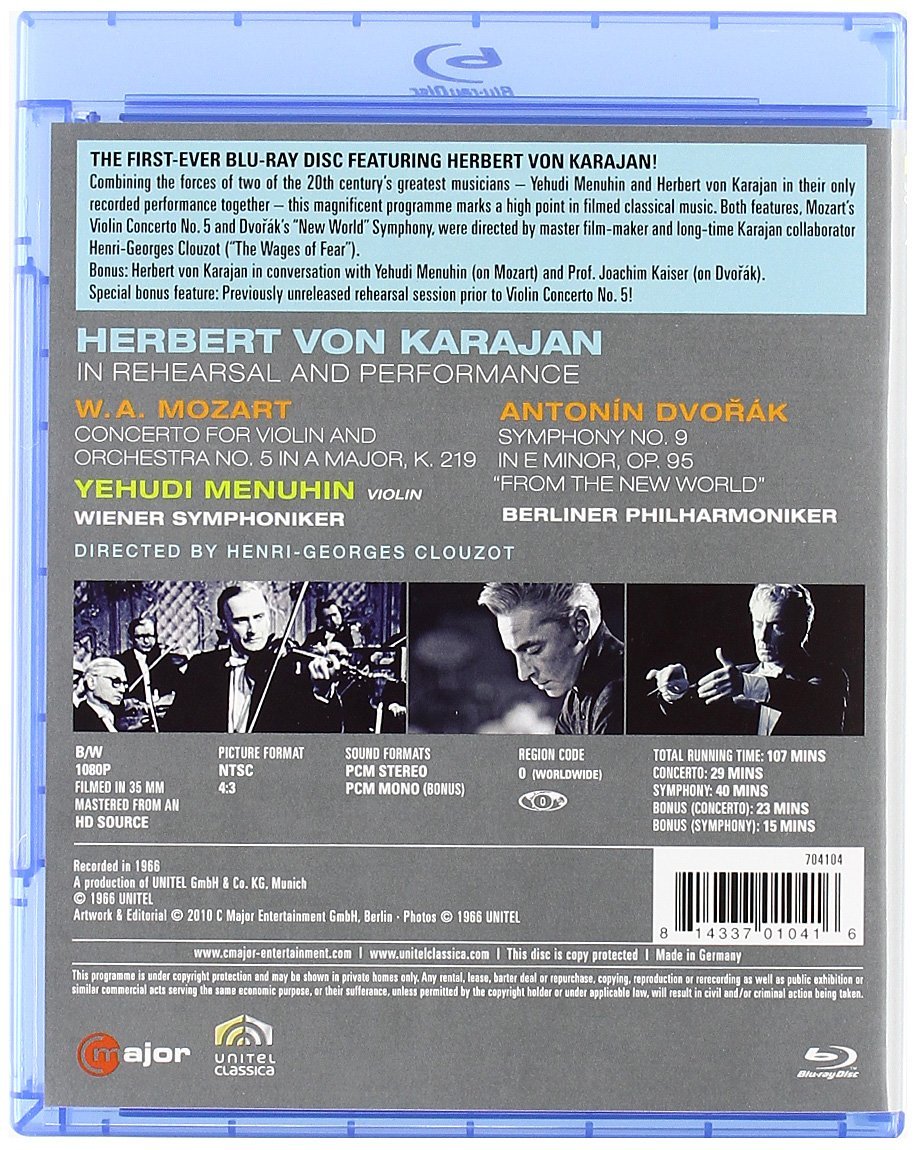

Herbert von Karajan 1965-1966 Movie Documentary. This title begins with a 1965 motion picture of Karajan conducting the Mozart Violin Concerto No. 5 with the Wiener Symphoniker and Yehudi Menuhin. Then comes the 1966 motion picture of Karajan conducting the Berlin Philharmoniker in the Dvořák Symphony No. 9 ("New World"). Finally, there are two bonus items in which Karajan discusses the art of conducting with Menuhin and Prof. Joachim Kaiser as well as a few minutes of Karajan in rehearsal. The filming was the work of motion-picture director Henri-Georges Clouzot. Released 2010, the entire title is in 4:3 black and white. It has PCM stereo sound for the music and mono sound for the extras. Grade: B-

Karajan was always interested in all aspects of recording technology. In the 1960s, he tried to increase his audience via motion pictures. He made a number of symphony movies with 35 mm film, mostly in black and white. He was about 50 years ahead of the market. The films cost a lot of money to produce and could only be shown in movie houses. The audience was too thinly scattered around the world for this to pay off. Eventually Karajan abandoned movie films to focus on LPs.

The original film prints shown in this title probably looked great in theaters. But that was long years ago, and the celluloid originals were soon put in storage to rot. The PQ of this title is only fair when compared to, for example, the HDVD version of the Casablanca film with Humphrey Bogart. The sound is straight-jacketed. All this disqualifies this title from our website as performance of a concerto or symphony. Nevertheless, the title is included here as a documentary about the history of fine-arts video.

The motion pictures of Karajan and his symphonic forces were ground-breaking. A number of operas were also produced as motion pictures. But I know of no other classical concert motion pictures. Some classical music titles were produced later in laserdisc and DVD, but these did not have high-definition video. Today we are getting HDVD classical music titles with PQ and SQ vastly superior to the Karajan movies. Still, the best of the Karajan movies were more striking than any other symphony video that was done since right up to the advent of HDVDs in 2007 (and maybe right up to today). That's because the Karajan movies were shot by Henri-Georges Clouzot, a fully-qualified and experienced motion picture director whose fame in his own field equaled the fame of Karajan as a conductor.

You have to see a couple of these Karajan/Clouzot films to understand what I'm talking about. The musicians in these films were made up, dressed, and positioned (usually very close together and in unusual formations) by Karajan/Clouzot on special stages with decorations and low-level lighting aimed at getting a film noir look. Our first screenshot is the most dramatic image I have found to illustrate this. (Please note this image is from a performance of the Beethoven Symphony No. 3 and is not from subject review title):

The image above is very poor, but you can easily see how shockingly different this is from a normal symphony concert. Is this genius or madness? This reminds me of those photos of the models created by Albert Speer and Adolf Hitler of the central city plan for Berlin as capital of the Third Reich. (Did you know that Karajan was a member of the Nazi Party?)

In the Karajan/Clouzot films, you don't see a microphone anywhere. Karajan looked more like a movie star than a symphony conductor. If you happened to see a few moments of this out of context, you might think it was a propaganda film or a crime thriller in which the conductor will be murdered on the podium.

Clouzot was obviously responsible for the film noir look. But who dreamed up the radical seating plans and the way the musicians were presented as soldiers of music or even robots? I have no idea, but all of this tied in well to Karajan's concept of the conductor as center of the observible universe.

The musicians were conducted by Karajan and directed by Clouzot simultaneously. No wonder they (all men---not a woman in the entire HDVD) all look so very intense and serious. The two films are quiet different, and the design of each is logically related to the character of the music. It's a little like the master chef who spends as much time working on how his dishes look as to how they taste.

With two such super-egos as Karajan and Clouzot at work, astonishing things were bound to happen. But with two such super-egos at work, things will not last long. After making 5 movies, the partnership broke up. Let's turn to some screenshots.

Mozart Violin Concerto

The music starts at the first frame of the film with this image:

Followed by this amalgam of Liberaceism and High Culture with many scores of actual burning candles (one for each musician plus general lighting). In addition to the kitsch, there was also a unique solar-system seating pattern with Karajan as the sun, the musicians in an asteroid belt, and Menuhin presented as a giant gas planet. I never figured out the empty seats:

The first obligation of the video director of any symphony performance is to show the audience adequate whole-orchestra shots so that viewers can, as when they attend a live performance, see where all the different instruments are located. (See our Special Article on this and other requirements for a good symphony concert video.) The solar-system setup made whole-orchestra shots impossible. Even with a camera on a crane, a chandeliers blocks the view:

Never mind, this performance is not about the orchestra. This show is about the sun and its planet:

Of course, the planet gets plenty of screen time in this concerto. So if you're interested in Menuhin, there's a lot for you to like in this performance and in a bonus extra:

But the real star is Karajan, and we see far more of him than this short piece for a chamber orchestra would seem to justify. I don't abhor conductors or belittle their contributions. I don't think the orchestra should have a committee to program a robot to conduct with little wiggling arms and flashing lights. But in this piece, Menuhin probably could have conducted as well as Karajan just by standing in the middle:

Karajan/Clouzot largely ignore the orchestra. But pretty soon the usual shots of the sun and planet start to get repetitive. So Clouzot moves to truly low-value angles such as the next 2 screenshots:

Usually it's easy to get whole-orchestra shots of a small chamber group. But faced with the asteroid belt, the best Clouzot could do was to show a few pieces of the orchestra action:

How (ignoring the merits of the performance, PQ, and SQ) would we grade the video content of this concerto by today's standards? I could give an A to the video of Menuhin's performance. But I would have to reduce the grade some for over-exposure of the conductor and even more for the shabby treatment of the orchestra. I would wind up with a "C."

Dvořák Symphony No. 9 ("New World")

Now we move to a full symphony film. Clouzot starts off with a dramatic film-noir reverse strip tease. First we see and hear mysterious cellos:

Wow. Doubled horns!

Also doubled clarinets:

Karajan laboring mightily literally in the thick of it:

OWG---double everything---what's the deal?

And now Clouzot opens his full-orchestra shot. Well, the best he can do is a 90% whole-orchestra shot that misses most of the bass violins and some of the 1st violins. Dvorak scored this for a normal symphony. But Karajan augmented the treble strings and doubled almost everything else, and this is more than Clouzot can handle. (With an orchestra this big we have the same problem today---our 1080 HD cameras can't provide adequate resolution to make a pleasant 100% image. We need 4K or 8K resolution to do this.)

After Clouzot's buildup, the shot below carries a punch. Now we get the picture---Julius Caesar is leading his Legion into battle. The troops are packed together in an impenetrable mass. They raise their instruments in unison, bow together, and move forward lock step grimly determined to conquer or die:

A shot of Julius fervently exhorting his troops to die without flinching:

With Clouzot's huge film cameras, there's no way to get a front close-up of Julius. So we get a lot of conductor shots over the backs of the the expendable troopers:

I shouldn't be too snide. This film does have many beautiful views of soloists and sections:

But what about the violins and violas? Well here they are. Can you tell who is who? There are too many players. The only hope to get a decent long-range shot was to pack all the strings as close as possible together. But even then Clouzot couldn't capture the conductor's vision and we are left with an unmanageable school of fish:

We end with a nice shot of the concertmaster and the 1st violins:

What does this suggest to us today? I believe the time has finally arrived when video directors and musical directors can work together as equals in producing HDVDs of symphonic concerts that will be compelling to consumers. A successful example of this would be the Vienna Philharmonic 2009 New Year's Concert title reported on this website. In that title Brian Large and Felix Breisach both contribute video of startling beauty. Large spices up the concert with shots of mountain landscapes, flower arrangements, and children dancing in the aisles. Breisach contributes fantastic bonus features where the video drives the music including dance numbers, the city of Linz as a performer, and members of the Vienna Philharmonic playing on fork-lift trucks and in an operating steel mill.

The work of videographer François Rousillon in opera and ballet titles shows how great the result can be when the video director is made an equal partner in projects from the beginning. But so far, no videographer seems to have developed enough clout to do this in the field of classical music.

Karajan and Clouzot could not make their partnership work because the their audience was spread out too much to fill movie houses. But today the right symphony director and right videographer can reach an audience profitably via creative and properly made $30 Blu-ray discs.

Update: It seems that Karajan, after giving up the partnership with Clouzot, tried again in the late 60s and early 70s to make symphony films with director Hugo Niebeling. The first image in this story (with the wedge-shaped platforms arranged like a Greek amphitheater) come from a Niebeling film of performances of Beethoven's Symphonies Nos 3 and 7.

I give the Dvořák Symphony part of this a B grade. I give this whole title the blended grade of B-.

OR