This title has a double bill of Tchaikovsky works, an opera and a ballet:

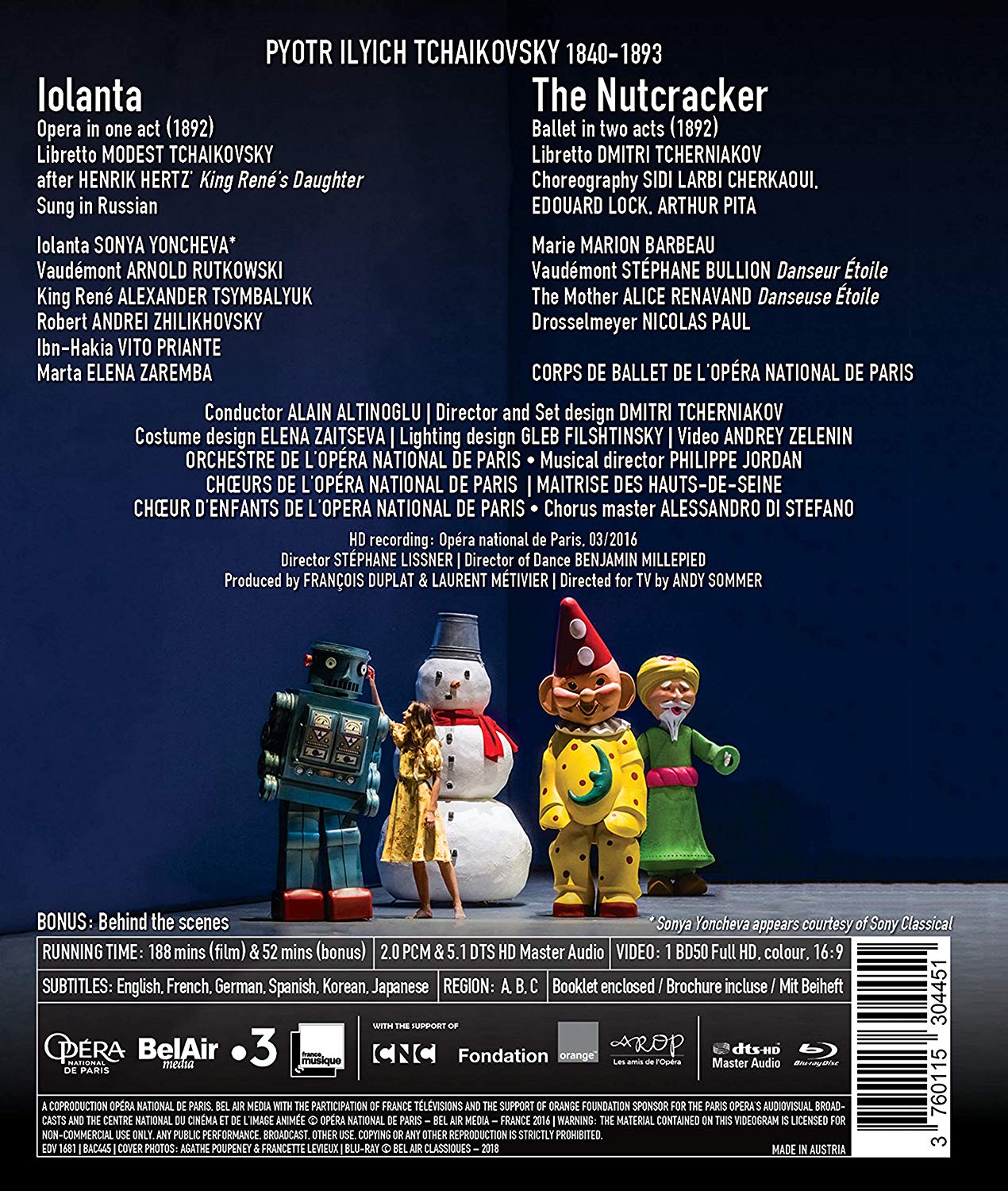

Iolanta opera to a libretto by Modest Tchaikovsky. Stars Sonya Yoncheva (Iolanta), Arnold Rutkowski (Vaudémont), Alexander Tsymbalyuk (King René), Andrei Zhilikhovsky (Robert), Vito Priante (Ibn-Hakia), Elena Zaremba (Marta), Roman Shulakov (Alméric), Gennady Bezzubenkov (Bertrand), Anna Patalong (Brigitta), and Paola Gardina (Laura). Sung in Russian.

The Nutcracker ballet to a libretto by Dmitri Tcherniakov. Choreography by Arthur Pita, Édouard Lock, and Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui. Stars Marion Barbeau (Marie), Stéphane Bullion (Vaudémont), Nicholas Paul (Drosselmeyer), Aurelien Houette (The Father), Alice Renavand (The Mother), Takeru Coste (Robert), and Caroline Bance (The Sister) supported by the Corps de Ballet de L’Opéra national de Paris.

For both productions: Directed 2016 by Dmitri Tcherniakov at the Opéra national de Paris. Alain Altinoglu conducts the Orchestre de l’Opéra national de Paris, Chœurs de l’Opéra national de Paris, Maîtrise des Hauts-de-Seine, and the Chœur d’Enfants de l’Opéra national de Paris (Chorus Master Alessandro di Stefano). Set design by Dmitri Tcherniakov; costume design by Elena Zaitseva; lighting design by Gleb Filshtinksy; video by Andrey Zelenin. Directed for TV by Andy Sommer; produced by François Duplat and Lourent Métivier. Released 2018, disc has 5.1 dts-HD Master Audio sound. Grade: A-

Iolanta and The Nutcracker, both shorter works, premiered together in Saint Petersburg in 1892. They were then, of course, completely distinct and unrelated works from Tchaikovsky. When Regietheatermeister Tcherniakov was hired to direct Iolanta, he talked the Paris Opera into allowing him to present the double bill again and to make changes to connect the two works. Tcherniakov specializes in making wrenching changes to opera libretti for startling purposes. The results range from horrible (Dialogues des carmélites) to marvelous (The Tsar’s Bride). (There were originally 5 choreographers hired to work on this. Two couldn’t stand the chaos and dropped out.)

As always with Dmitri, you pay your money, watch, and then you can vote. Well, we gave this an A - grade, but that grade has nothing to do with our usual grading explanations. Here the A stands for “audacity” on the part of everybody involved with this project. We knock the grade down with a “-” on account of a scrim that degrades a number of images in the video.

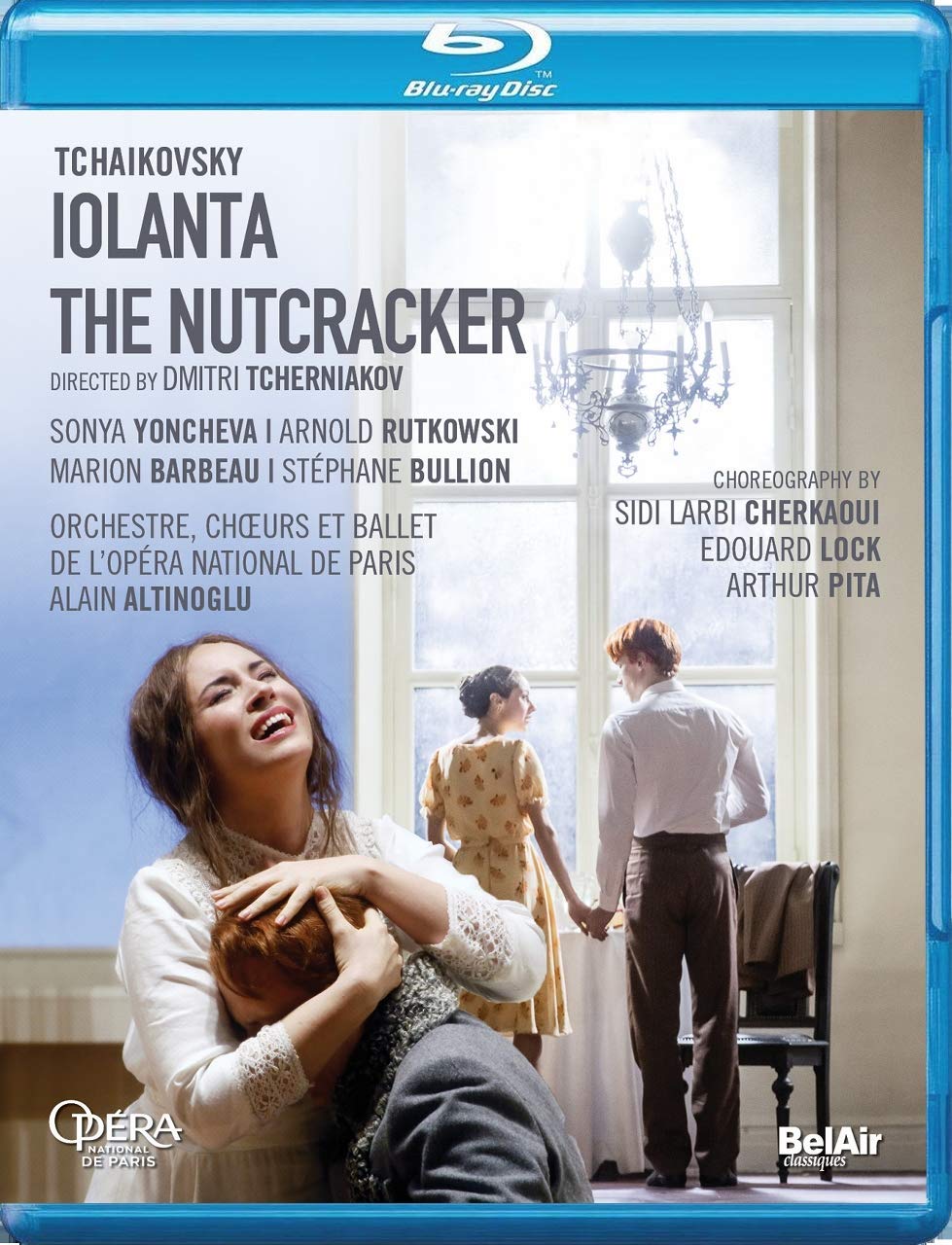

To begin, we call your attention to the front cover art from the keepcase. In the foreground you see the virgin princess Iolanta (soprano Sonya Yoncheva) embracing her knight Vaudémont (tenor Arnold Rutkowski) who happens to have red hair. In the background next to the window you see the same couple with the virgin future heiress Marie (ballerina Marion Barbeau) holding the hand of her dreamboat friend Vaudémont (danseur étoile Stéphane Bullion with a red wig). We are seeing the same couple in two different versions, one in an opera and the other in a ballet. And they both have (pretty much) the same family members and friends! The big difference between the couples is that in the opera, Iolanta is blind and will come to learn something about the light. In the ballet, Marie is sighted but have to contend with the dark.

Fear not: it gets even more complicated as you contend with 8 “literary” or “meta" artistic creations: 2 musical compositions by Pyotr Tchaikovsky, an opera libretto by Modest Tchaikovsky, a ballet libretto by Tcherniakov, opera direction by Tcherniakov, and 3 separate working styles by choreographers Arthur Pita, Édouard Lock, and Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui! It would also appear that the entire Opéra national de Paris organization put its considerable resources wholeheartedly behind the effort to make this show a technical as well as artistic extravaganza.

Iolanta Opera

In a rather improbable plot, Princess Iolanta (Sonya Yoncheva) was born blind. Here we see her with her Governess Marta (Elena Zaremba) and two nurses, Brigitta (Anna Patalong), and Laura (Paola Gardina) in a secluded secret estate where Iolanta lives in complete isolation. She has never been told she is blind and none of her “friends” have ever said in her presence anything about vision, light, or physical beauty. But Iolanta feels something is amiss — does she sense that others have powers of observation that she lacks, or is she longing for a boyfriend, or both?

King René (Alexander Tsymbalyuk) has kept his daughter ignorant of her handicap to spare her from grief while the King searches for a cure. He now visits the secret estate with a renowned Moorish physician, Ibn-Hakia (Vito Priante) who, it seems, can cure blindness:

Iolanta is usually staged in a fabulous garden hidden in a vast forest. It’s plausible then that her knight of her dreams might accidentally wander into her paradise. But this Iolanta has to be set indoors (later you see why), and her knight Vaudémont (Arnold Rutkowski) has to climb through a window. Well, Tcherniakov pulls this off in a way that deflects you from immediately noticing the absurdity of the situation and just goes on to prove that in opera, anything can happen. Well, Vaudémont is an idealistic dreamer and is instantly captivated by the beauty of Iolanta when he discovers her taking a nap. When she awakes, Vaudémont goes into high gear exclaiming (in words Iolanta has never hear before) how he fell for her vision of loveliness the moment his eyes saw her, etc.

The strange conversation that follows baffles Vaudémont:

Until Vaudémont notes that Iolanta can’t tell a white rose from a red one and figures it out:

Vaudémont explains the light to Iolanta:

But he overstates when he says that one without vision cannot understand the glory of God. Iolanta corrects him and Vaudémont falls completely in thrall. At this point we have to point out the unhappy scrim that apparently covers the whole stage and often can’t be avoided, it seems, by videographer Andy Sommer:

The music of Peter, the words of his brother Modest, and the directing of Tcherniakov, together with the singing and acting of our stars produces a churning of emotion that is truly remarkable just a few minutes into a one-act opera:

But whoa, who is this skinny girl in a yellow dress who wanders into the scene?

Well, it’s Marie, Iolanta’s alter ego. And as you can see from the next screenshot, this opera about seeing the light is a play that is being performed at Marie’s birthday party! The scene with the new lovers was so compelling, Marie walked into the play!

Now it’s time for the first curtain call. Below all the members of the Iolanta cast are lined up (including a few we didn’t meet earlier in this review). Iolanta is seen moving in front starting to lead the cast off the stage:

The audience continues to applaud, so the cast comes back on stage for more bows. Look closely at the screenshots above and below. The costumes are the same, but (with the exception of Iolanta) the people are all new. Each of the players in the opera (other than Iolanta) has been replaced by a ballet dancer!

Nutcracker Ballet

After more milling about, we have an all new (except for Iolanta with her red rose) and larger cast of ballet dancers playing roles of participants at Marie’s Nutcracker birthday party (no hint of Christmas). When Tcherniakov agreed to work on a double bill project at the Paris Opera, Marion Barbeau had only recently joined the Paris Corps and was probably a quadrille or coryphée. Tcherniakov spotted her, thought she had the right look, and proposed to make her the star of the Nutcracker portion of the show. This would be a bit like promoting a lieutenant in the Army to general — in the Paris Opera Ballet you work your way up rank by rank. But eventually Tcherniakov got his way. (This reminds us of the fantastic break Laura Day got in creating the role of Grete Same in the Metamorphosis dance project at the Royal Ballet.) Barbeau, who appears to be among the lithest of the Paris ballet women, took full advantage of the opportunity and seems to be tireless in a long, difficult, and strenuous role.

After a few more seconds, Iolanta will quit the scene and we will be firmly engaged with enjoying Marie’s party. The music is all familiar, but the completely new party choreography is by Arthur Pita, a narrative ballet genius whom we know from his unforgettable Carmen street scenes and his groundbreaking creation The Metamorphosis. Look carefully below, Iolanta’s red rose is sitting on the piano!

Here’s our Nutcracker as a piñata!

Throughout the party Marie feels an overwhelming attraction to guest Vaudémont (Stéphane Bullion). After the party, Vaudémont returns and Marie gives him the red rose that Iolanta left behind. We don’t figure out until later that Marie has gone to bed and what we are seeing now is her nightmare:

Just as the naughty boys in the Nutcracker become rat soldiers in Clara’s dream, the jovial guests at Marie's birthday party suddenly turn into sinister characters attempting to start an orgy in Marie’s living room. And who could do a better job of this than Édouard of old, the inventor of Lock logic. We didn’t know Lock was still alive and still working as choreographer:

Lock insists that you don’t need music for ballet. (If ballet was part of music, it would be be taught at conservatories.) He gives his dancers all their moves in silence. Music is added in later because that’s what the public expects. But his art is a form of intellectual athleticism founded on the delight of proprioception and not on the love of music. He has his own unique alphabet of tiny, precise, dramatic movements to be performed at breakneck speed. Lock long ago created the fabulous dance motion picture Amelia. Here’s what we said about Lock logic back then:

“The dancers . . . display bi-polar, manic levels of energy . . . to strive to break free. Thus Lock logic breaks through our normal perception of dancers and leads to what Lock calls a "deconstrutive revelation" of their bodies, and. . . their souls. In English, Lock is trying to shake you up so you can really see and appreciate the dancers. Because of the deconstructive revelation Lock achieves, [his work] is absorbing throughout, and the dancing is consistently awesome.”

This time around, Lock in the bonus extra describes his logic in fewer words: “ Within the chaos of details there exists a harmony that loathes to be harmonious.” H’m. Same thing. Tcherniakov wants to get into Marie’s subconscious desires, and Lock logic is the way to do it.

The most spectacular display of Lock logic we have observed would be swivel hip moves performed by Barbeau with the aid of Bullion and seen (poorly) in the next screenshot below. This move reminds us of dolls girls used to play with where the legs were attached to the torsos with brass rivets. The legs would rotate 360° spinning like an aircraft propeller. Well, we don’t think the human being is equipped with the necessary muscles to make this move alone. But in the screenshot below, Lock gets the swivel going with Bullion supporting and moving Barbeau’s thigh. This is all done at an astonishing speed and is the spookiest, most bizarre dance move we can remember seeing:

The nightmare party ratchets up in sexual tension until, in a cataclysmic explosion, the entire house set disappears in a hailstorm of flying debris! (We have no idea how this was done.) Now we see why the set includes that scrim that kept getting in Andy Sommer’s way. It’s there to give the audience in the theater and at home the illusion that the world is completely splattered with mud. In a instant we have gone from scenes of a wild party to scenes of total devastation. And we have also changed to choreography by Sidi Larbi Cherkaoui. According to Barbeau’s comments in the bonus extra, “Larbi” uses a completely different style of dancing from Pita or Lock that is based on fluid motion and lots of artful falling. Larbi is assigned the “snow” scene immediately below:

Later, to the music of the Waltz of the Flowers, Tcherniakov and Larbi come up with images of grotesquely injured walking wounded writhing in a blackened debris field. Even worst, Vaudémont dies and disappears leaving Marie alone:

After the waltz in the dump, the nightmare moves on to a dark forest with more Lock logic. Marie looks for Vaudémont everywhere, and the harder she looks, the more examples of him she can find — but each alleged Vaudémont turns out to be an illusion! The forest scene is loaded with state-of-the-art video images that can’t be rendered into simple screenshots:

Next Marie makes it to the Land of Sweets where she is confronted by multiple doppelgänger invigorated with more Lock logic:

Each of the giant dolls has a dancer inside providing slow motion while the multiple Maries frantically agitate:

Lock gives senior danseuse étoile Alice Renavand an explosive solo with tricky moves performed in heels, which she knocks out in style:

And now we are back to Larbi again with a lascivious pas de deux. Marie has burned enough birthday cake candles now and is ready for more serious action:

But before she can get any satisfaction, a sudden celestial phenomenon interrupts her dream:

End of file:

Now the real curtain call begins. Yoncheva seems throughout to be having fun. Barbeau is totally wiped out from continual exhausting efforts.

We were convinced that baritone Vito Priante was allowed to play both Ibn-Hakia in Iolanta and Drosselmeyer in Nutcracker. Wrong again. So who is who? Well, the dancers tend to be a bit skinnier than the singers. So we think the gent below on your left is dancer Nicolas Paul and the singer Priante is on your right:

This review has been too long, but there are still many aspects of this we haven’t touched on. Once again, the A grade here is for audacity and doesn’t mean this show will appear to everyone. To the contrary, this title will appear mostly to folks who love all three of the following: opera, ballet, and puzzles.

Here are 2 official YouTube clips: (one from BelAir about the disc and the other from the Paris Opera about the show):

OR