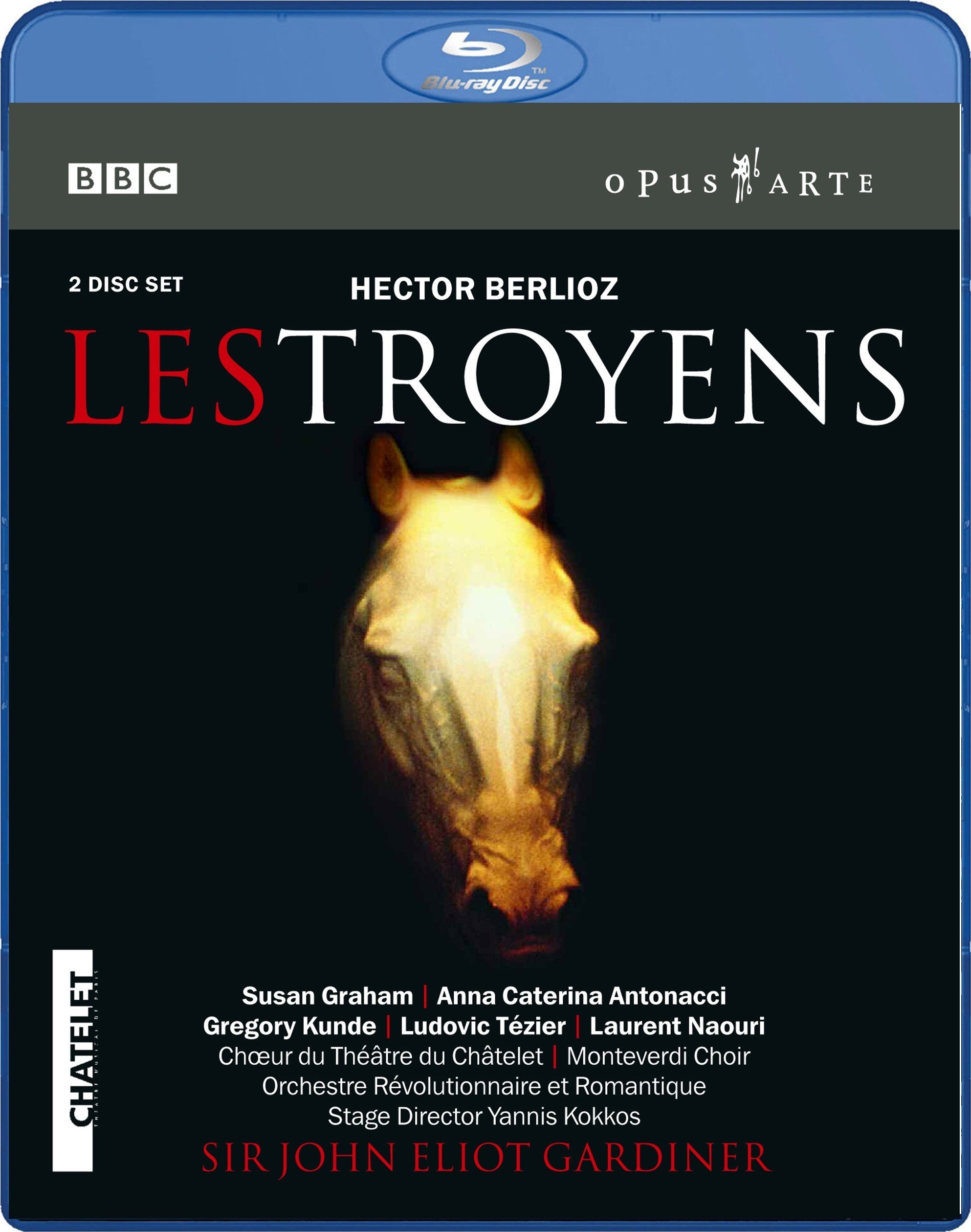

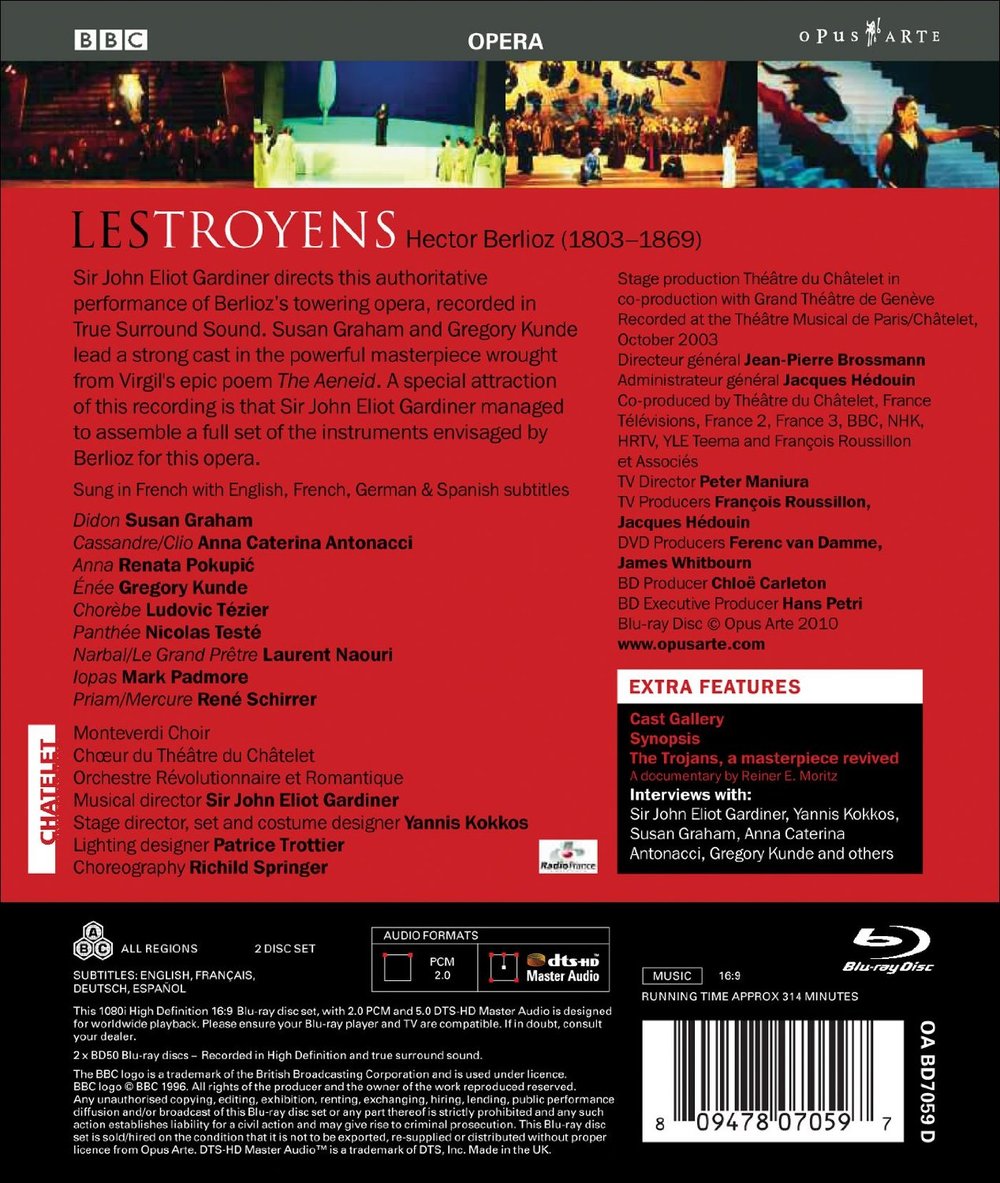

Berlioz Les Troyens opera to libretto by the composer. Directed 2003 by Yannis Kokkos at the Théâtre du Châtelet in Paris. Stars Susan Graham (Didon), Anna Caterina Antonacci (Cassandre/Clio), Renata Pokupić (Anna), Gregory Kunde (Énée), Ludovic Tézier (Chorèbe), Nicolas Testé (Panthée), Laurent Naouri (Nalbal/Le Grand Prêtre), Mark Padmore (Iopas), Stéphanie d'Oustrac (Ascagne/Une soprano), Topi Lehtipuu (Hylas/Hélénus/Un tenor), Fernand Bernadi (Le Fantôme d'Hector), René Schirrer (Priam/Mercure), Danielle Bouthillon (Hécuba), Laurent Alvaro and Nicolas Courjal (Deux Sentinelles Troyennes), Benjamin Davies (Un Soldat), Robert Davies (Un Chef Grec), Frances Jellard (Polyxèna), Lydia Koniordou (Andromaque), and Quentin Gac (Astyanax). Sir John Eliot Gardiner conducts the Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique, the Monteverdi Choir, and the Chœur du Théâtre du Châtelet (Chorus Master Donald Palumbo). Set and costume design by Yannis Kokkos; lighting design by Patrice Trottier; choreography by Richild Springer. Directed for TV by Peter Maniura; produced for TV by François Roussillon and Jacques Hédouin. Sung in French. Released 2010, two-disc set has 5.0 dts-HD Master Audio sound. Grade: A+

This title was the first Blu-ray release of Les Troyens. Gordon Smith saw this soon after its release and here are his comments:

“Recorded in 2003, this production was hailed as a landmark event in every respect when it came out on DVD. Now we have it in Blu-ray HDVD with its impressive staging using front projection and a huge inclined mirror to reveal a whole new perspective of the action (and at times "doubling" the number of people on stage). And then there is the playing of the Orchestre Révolutionnaire et Romantique with authentic Berlioz epoch instruments (on stage as well as in the pit) expertly conducted by Sir John Eliot Gardiner. Not to mention the combined Monteverdi Choir and Châtelet Théâtre Choir. Their contribution is one of this production's most outstanding features, since their crisp, perfectly controlled singing clearly shows that Berlioz was a supreme master of choral writing. And the soloists! Anna Caterina Antonacci as Cassandre is incredible! Her presence, acting, and powerful voice give huge dramatic impact to the first two acts. She sets the standard so high, you wonder if the rest of the cast could match it! Well they do! In particular, Susan Graham shines as Dido, matched by American tenor Gregory Kunde as Aeneas. With razor sharp images and thrilling sound in Blu-ray, this should be a cornerstone of the collection of every dedicated HDVD enthusiast.”

Berlioz finished Les Troyens in 1858; he never could get it performed whole. It took 145 years for the folks at Châtelet to first perform the opera in a manner that Berlioz probably would have been completed satisfied with! After this Châtelet version was released, we also got in 2011 a space-age Fura dels Baus version from Valencia and, in 2013, another important traditional version from the Royal Opera House. So it is time now to review all three HDVDs. (In the Châtelet and Valencia reviews, I'll use the names of the characters in French; I'll use the English names in the ROH review.)

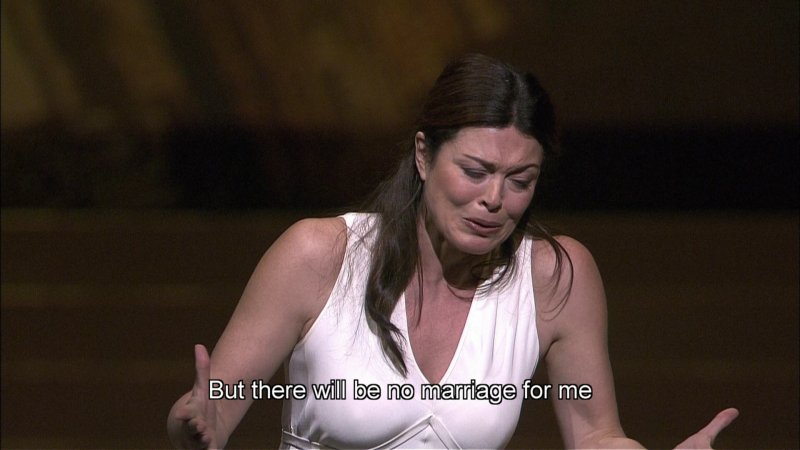

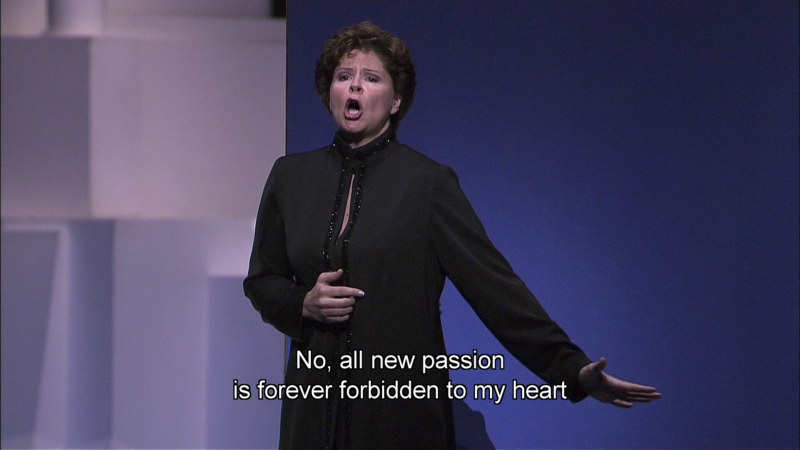

In the May 2014 Opera News (page 12) the Italian soprano Anna Caterina Antonacci says, "When I sang Cassandre at the Châtelet [in 2003], it turned into an unexpected success for me . . . and it changed the course of my career. I discovered the French repertoire and adopted it, and the French adopted me." Antonacci was about 42 at the time, but she was fit enough to convincingly play the role of a virgin princess. Cassandre, a daughter of King Priam, was a seer whose predictions were too grim for anyone to believe. Below Cassandre laments that she will never marry because she will soon die in the destruction of Troy:

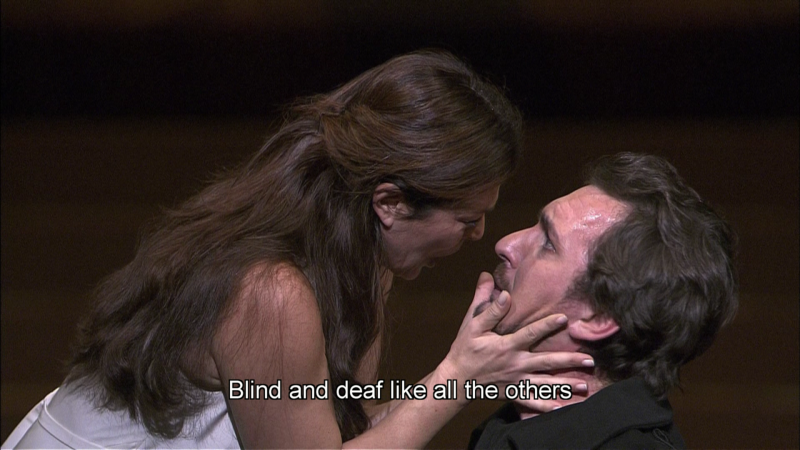

Here are 3 great shots of Ludovic Tézier singing Chorèbe, a prince engaged to Cassandre. Cassandre begs him to flee Troy. But in the first of many wonderful duets in this opera, he convinces Cassandre that he would rather die defending her than live on without her. These shots illustrated the fine acting ability of the singing stars in this production as well as the great near and close-up videography provided by François Roussillon (acting this time as producer):

The people of Troy believe the Greeks have admitted defeat and departed leaving a giant horse behind. Priam conducts a royal celebration of thanksgiving. Here we see Hector's widow Andromaque (Lydia Koniordou) and their son Astyanax (Quentin Gac). Note the drab costumes. The Châtelet folks spent a lot of money on singers. There wasn't much left for sets, costumes, or props. Because of this, the royal event here is distinctly underwhelming:

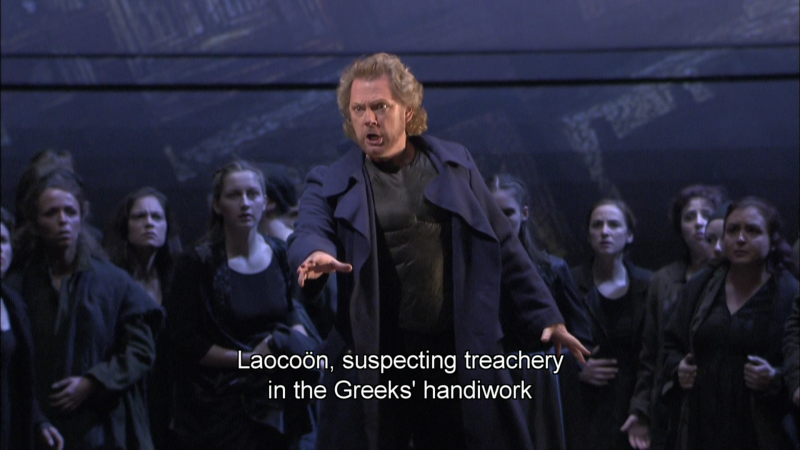

Énée (Gregory Kunde) bursts on stage to describe the fate of Laocöon, who wanted to destroy the Trojan horse at the beach. Serpents came out of the sea and ate Laocöon; this convinced the Trojans that the horse was left behind as an offering by the Greeks to the Trojan gods. The Trojan horse is, of course, an symbol of the human tendency to engage in wishful thinking following a success. This is why military doctrine now requires that anytime you successfully take an objective, you must immediately prepare for a counterattack. Today the Trojan horse story resonates deeply with the French: after WW I, they built a Trojan horse themselves—the Maginot Line. Having exhausting themselves wishfully pouring concrete, there was no energy left to build what they actually needed: a mobile army that could respond quickly to attack from any direction:

Meet Stéphanie d'Oustrac as Ascagne, Énée's son. Stéphanie is such a sexy woman, it's hard for her to put on trousers:

The Trojan horse looked better on the keepcase cover than it did on stage. I read somewhere that Berlioz didn't expect the horse to be seen; but we do:

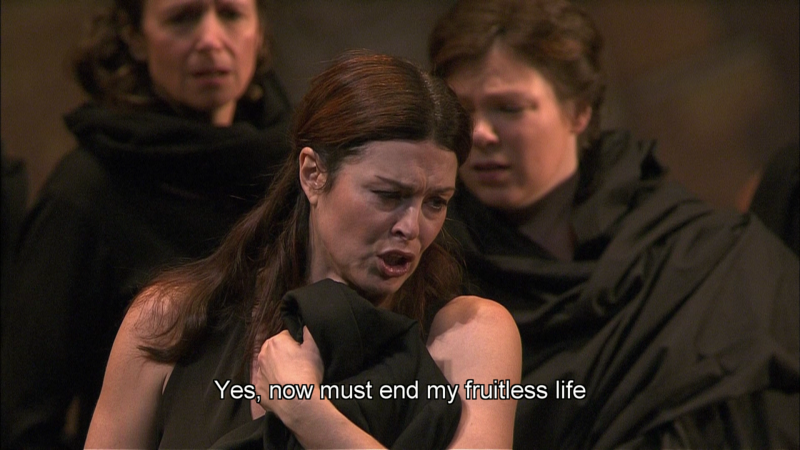

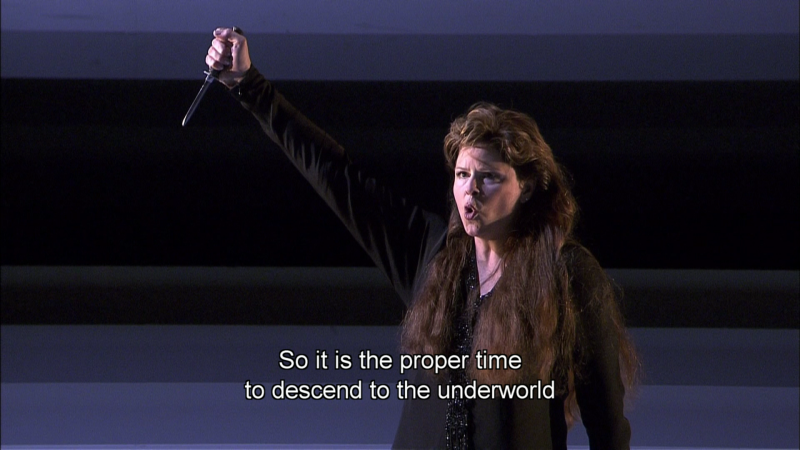

Act 1 ends after the Trojans drag the horse into the city. When Act 2 opens, the Greek commandos have emerged from the horse, killed the (drunken) Trojan guards, and signaled to Greeks forces hidden nearby to pour into the city. The ghost of Hector appears to Énée and orders him to flee Troy and sail for Italy, where he will found a new and better state. The women are left to face rape and captivity. Cassandre announces her intent to commit suicide:

Cassandre's closest friends join her in death. Help me out on this: Énée and his men were ordered by God to high-tail it for Italy. But how do they start a new people and state after abandoning their women? How did Virgil deal with this messy detail?

Act 3 opens in Carthage where we meet Queen Didon (Susan Graham). Didon and her people are refugees from Tyre who only seven years before landed in North Africa and founded Carthage. The Châtelet costume shop continues to dress the leaders in black, but the people get mostly white to wear. This scene reminds me of what you might see at a religious pageant at one of those Protestant megachurches in the United States:

Didon is a widow who is determined to remain faithful to her dead husband:

But her sister, Anna (Renata Pokupi), wants Didon to follow the "gentle law" of marriage because every kingdom needs a king. This leads to another of the wonderful duets I mentioned earlier:

The Trojans were sailing for Italy when their fleet was thrown off course and damaged by a terrible storm. Through his son Ascagne (who is about 11), Énée is granted safe harbor in Carthage. The Trojans make it clear they only need relief for a few days before they sail again for Italy:

But next Didon learns that Carthage is being attacked by neighbors from the south. Carthage is short on soldiers, and the Trojans are well-armed, battle-hardened warriors. Act III ends as Didon and Énée agree to an alliance against the Africans (in passages that are no longer politically correct):

After the end of Act 3, Didon and Énée defeat the Africans. The climax of the opera comes in an Interlude between Act 3 and Act 4 called the Royal Hunt and Storm. In a sacred cave, nymphs and fauns dance madly to wild "orgasm music." Énée and Didon demonstrate the power of the Sexual Imperative by making love even though Énée is under orders from God to reach Italy and Didon has sworn to never love again. Alas, the Châtelet director had no money for nymphs, fauns, a cave, or even a wind machine. The music is played just fine, but all you see is a bad video of a white horse running around and Susan Graham running across the stage dressed in a flowing red dress with a huge train (no screenshots of that).

In Act 4, good things start to happen again. There is a memorable duet between the Prime Minister Narbal (Laurent Naouri) and Anna. Narbal is worried that Didon is neglecting the state, and Anna is optimistic than the state will be safer when Énée and Didon marry. The duet ends with this neat image:

As Didon, Énée, and others relax, Iopas entertains with a lovely solo thanking the god of the wheat fields:

And while the singing continues, Ascagne slips from Didon's hand the ring given her by her deceased husband. Now everyone sees that Didon and Énée are lovers:

Now Act 4 moves to a new level of ethereal singing celebrating the love of Didon and Énée. In my HT, I can hear the orchestra in the pit, the chorus in the background, and then a mysterious layer of voices in the foreground singing in various combinations. This leads to a glorious septet with (from left to right) Ascagne, Didon, Anna, Énée, Iopas, Narbal, and Panthée (Nicolas Testé):

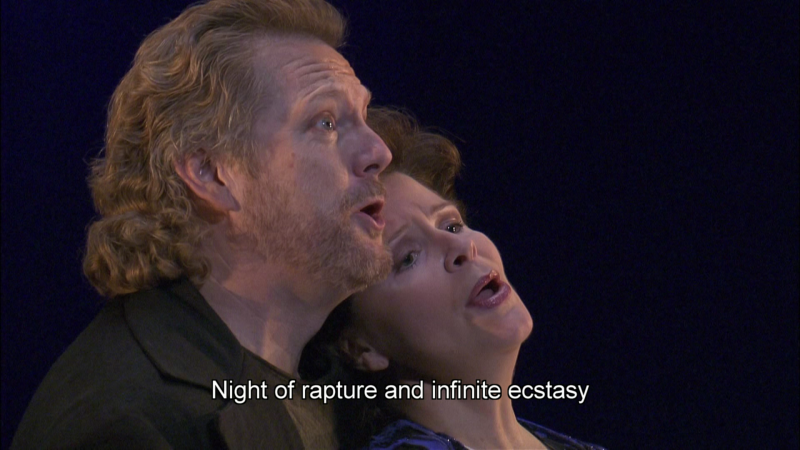

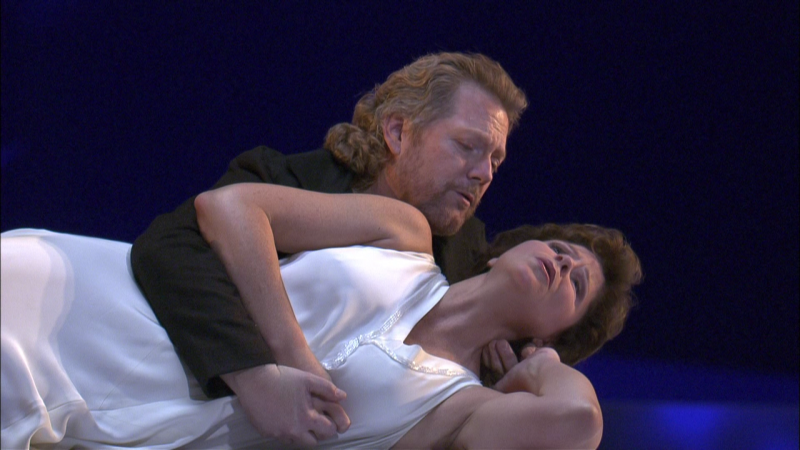

Eventually the lovers are left alone and the grandest duet of all is, of course, between them. A would say that in Act IV we are treated to about 40 minutes of the best ensemble singing I know of in today's galaxy of HDVD operas. This disc is worth its price just to get Act 4:

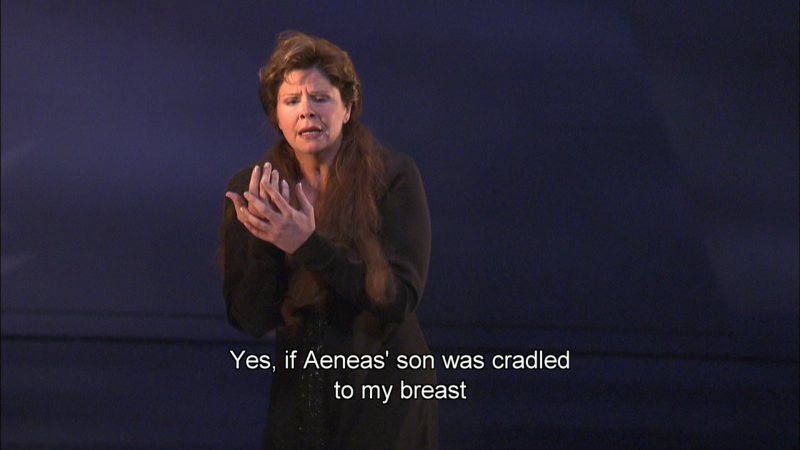

Well, you know how long the best things last. In Act V, God sends Mercury to Énée with orders to sail immediately to Italy. Didon, who has just given in to Énée, is jilted within hours. In an acting tour de force, Graham first feels sorry for herself:

But she soon shifts into a terrible fury. She should have foreseen the betrayal by Énée. She should have arrested him . . . :

Shamed to the quick, Didon predicts:

Didon proceeds to commit suicide:

Led by Narbal, the people of Carthage also pray for revenge:

Alas, we know what happened to Carthage. Didon was just another Homer-like temptation for Énée to overcome on his way to founding the glory of Rome. And since the Carthaginians had sworn eternal hatred for Rome, it would only be just for the Romans to eventually to destroy Carthage. The ghost of Cassandre reappears for the last words in the opera (rendered in Latin), "Fuit Troja / Stat Roma." (Troy was. Rome stands.)

Gordon's assessment of this title as as "cornerstone" still holds. The singers here are probably the best ever assembled for Les Troyens. They were also all good actors who were beautifully directed and lovingly photographed. The period-instrument orchestra sounds fetching with this score, and the balance between singers and orchestra always seems good to me. But there are deficiencies. The sets are plain. I personally don't much care for big mirrors on stage because they always show a lot of distortion of the images and can be distracting and confusing. The costumes were worse than plain; the props almost laughable. The Royal Hunt and Storm may have looked mildly interesting in the theater, but it's a miserable flop in the video. Finally, there are some dancers and acrobats in this production. But I think you could find dancers and cheerleaders in the high schools and colleges of the United States who would be more skillful than the entertainers hired by the Châtelet. (I was impressed by that guy walking on the big blue ball).

So if you are of the view that the music, singing, and acting is all that really counts in an opera, then this is the best recording ever made of Les Troyens and deserves Gordon's A+ grade, which we will keep.

But if you would like a more complete package, check out the Royal Opera House version as an alternative.

We end with an observation form Wonk John Aitken about the ending of the Châtelet production. This version ends with "Fuit Troja/Stat Roma." This is the original Berlioz ending with Clio, the Goddess of History (often presented as Casandra), wrapping things up. Berlioz eventually wrote a shorter version with more punch, and that's how the Royal Opera House version ends.