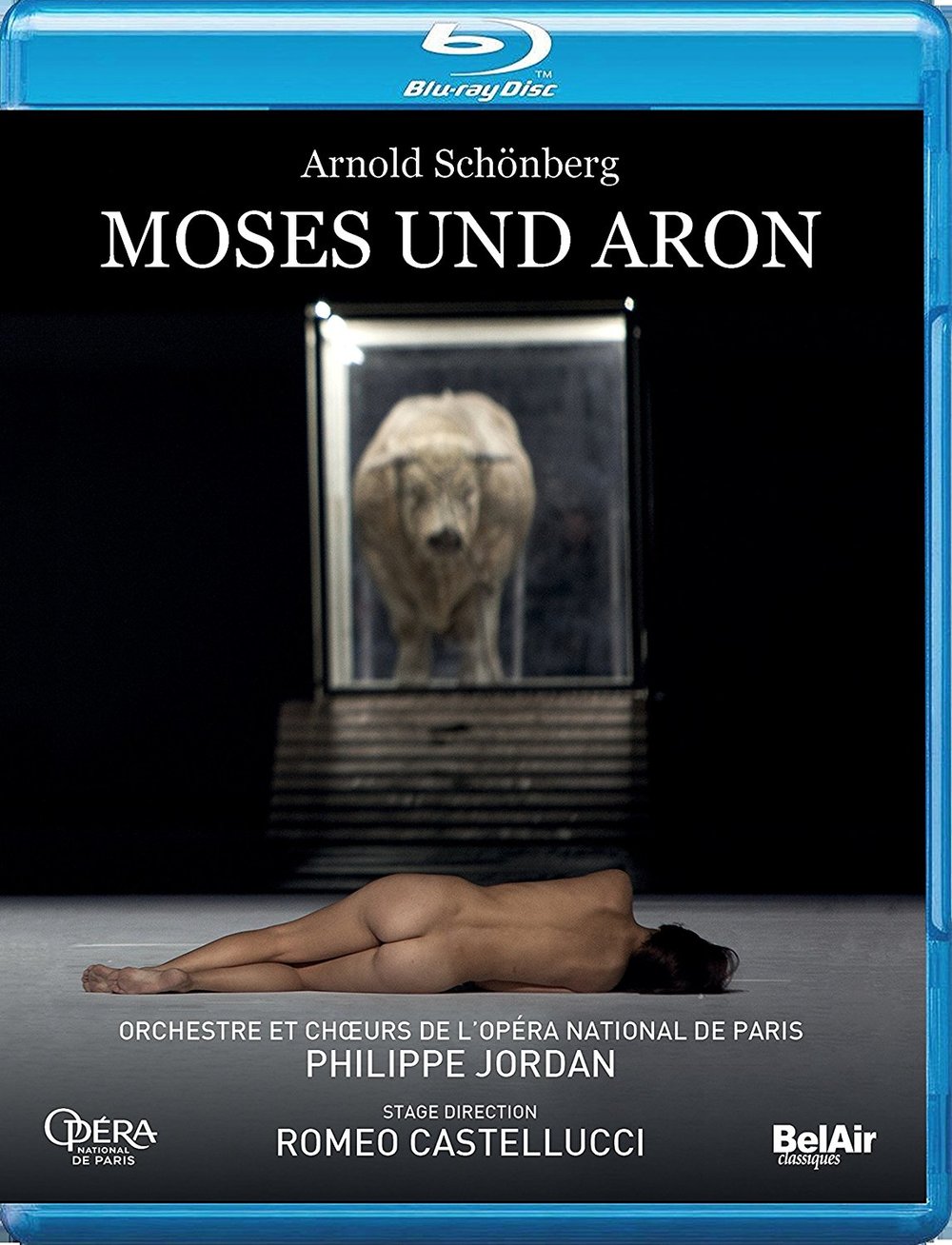

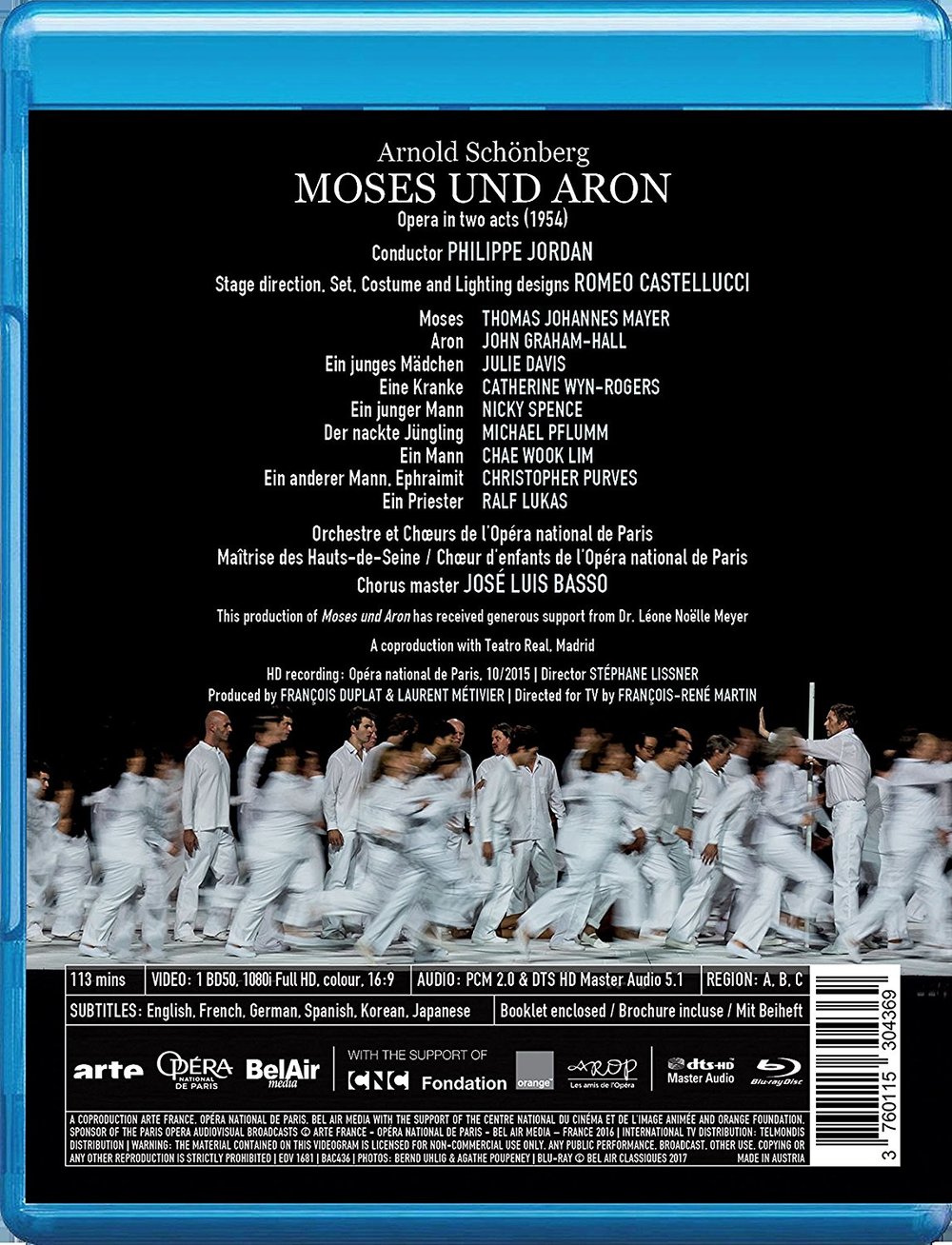

Schönberg Moses und Aron opera to libretto by the composer. Directed 2015 by Romeo Castellucci at the Paris Opera House (Bastille). Stars Thomas Johannes Mayer (Moses), John Graham-Hall (Aron), Julie Davis (Ein junges Mädchen or Young Girl), Catherine Wyn-Rogers (Eine Kranke or An Invalid Woman), Nicky Spence (Ein Junger Mann or A Young Man), Michael Pflumm (der nackte Jüngling or The Naked Youth), Chae Wook Lim (Ein Mann or A Man), Christopher Purves (Ein anderer Mann/Ephraimit or Another Man/Ephraimit), Ralf Lukas (Ein Priester or A Priest), Julie Davies, Maren Favela, Valentina Kutzarova, and Elena Suvorova (Vier Nackte Jungfrauen or Four Naked Virgins), Shin Jae Kim, Olivier Ayault, Jian-Hong Zhao (Drei Älteste or Three Elders), as well as Béatrice Malleret, Isabelle Wnorowska-Pluchart, Marie-Cécile Chevassus, John Bernard, Chae Wook Lim, and Julien Joguet (Sechs Solostimmen or Six Solo Voices). Philippe Jordan conducts (1) the Orchestre et Chœurs de l'Opéra national de Paris and (2) Maîtrise des Hauts-de-Seine or Chœurs d'enfants de l'Opéra national de Paris (Chorus Master José Luis Basso and Deputy Chorus Master Alessandro di Stefano). Sets, costumes, and lighting by Romeo Castellucci; choreography by Cindy Van Acker; artistic collaboration by Silvia Costa; dramaturgy by Piersandra Di Matteo and Christian Longchamp. Directed for TV by François-René Martin; produced by François Duplat and Laurent Métivier. Sung in German. Video recorded in 2.20 format in order to meet the Director’s visual wishes while avoiding problems with sub-title readability. Words projected onto a scrim on the opera stage were in French. Released 2017, disc has 5.1 dts-HD Master Audio sound. Grade: A with ‽ warning

This is (January 2020) the only HDVD of Moses und Aron (there are some CDs and two DVDs). Even though it’s some of Schönberg's most difficult music, the score is now 85 years old and no longer sounds particularly strange to modern ears. Castellucci's stupendously abstract production occupies some of the no-man's land between opera, ballet, and staged oratorio and appears to me to be as aggressively up-to-date as possible. Fred Cohn, writing in the October 2017 Opera News, says this was the "first new production of Stepháne Lissner's tenure as director of the Paris Opera, and it is hard to imagine a more decisive declaration of seriousness of purpose."

Schoenberg was a Jew who converted to Christianity as a young man in 1898. But he still faced relentless discrimination on account of his ethnic origin and return to Judaism in 1933 as part of his personal battle with anti-Semitism and Fascism. Moses und Aron was published in 1932. Here’s my best guess at Schoenberg’s thesis: Moses led the way in showing the world that God is an idea and cannot be adequately represented by an idol. But mankind has still not completed the pilgrimage that Moses began because there are still many religions, each bound to its particular images. All these religions should shed their trappings and unite in worship of the sole idea of God. To make at least one small step in this direction, Schoenberg invented dodecaphony, a form of music that should be, going forward, equally available to all the cultures of the world. H’m doesn’t seem like a fun evening at the opera; but let’s get dressed, as this will doubtless be good for us.

The opera opens with a vast white scrim covering the stage. At first Moses appears in front of the scrim dealing with the voice from the burning bush (presented as a reel to reel tape recorder spewing out piles of magnetic tape which will be seen many times later). The voice commands Moses to free his people (and all the peoples of the earth) from the captivity and idolatry represented by the scrim. Moses, who is not glib of tongue, accepts the order because he can rely on Aron to speak to the people. (Schoenberg deliberately spells Aron with a single “a”.) Our leading screenshot shows Moses (Thomas Johannes Mayer) on the right and Aron (John-Graham-Hall) on the left behind the scrim discussing their mission. The French word for “brother” is projected on the scrim. Throughout Act 1 hundreds of other French words will be presented to the audience in this manner— a great exercise in speed-practicing your French vocabulary. Note the special (maybe unique) tall black field on the bottom of the screenshot. There is a lot of verbiage in this libretto. The black band was created to make it easier to clearly project the text in subtitles while not interfering with the video images and the French vocabulary exercise:

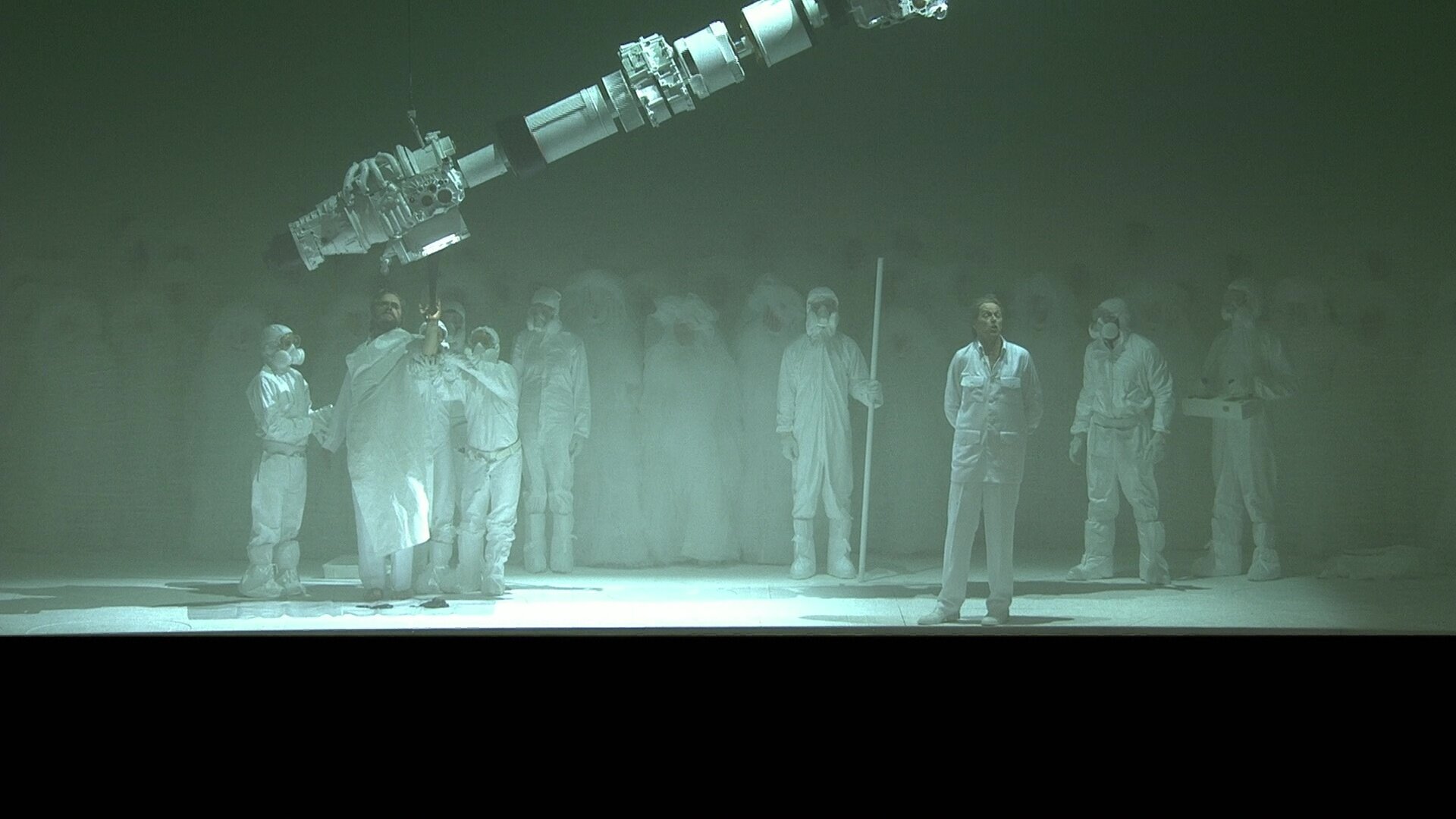

Below we see (sort of) the people of Israel wallowing in ignorance throughout Act 1. Critics called this the “Milk of Magnesia” act. You were warned this would be a difficult show:

Three miracles are explained by Aron to convince the people that Moses is a powerful prophet who can be trusted. In the 1st miracle, the staff of Moses turns into a serpent. Here the serpent is represented by a strange but realistic looking machine. I think Castellucci went to a heavy-industry tool maker to find the parts for this weird prop. It looks like two engines or transmissions set up to rotate a connecting axle in one direction. Could the two machines represent the two brothers working in different directions toward one goal? The word “saltpeter” suggests the serpent is dangerous, but this is just one of many words that get flashed on the scrim in respect to the machine:

In the 2nd miracle, Moses’s leprous hand is healed (by black goo that oozes out of the serpent):

The hazmat-protected attendants of the serpent pull out a long glass vial filled with clear liquid. This is water of the Nile which turns to blood (of the Pharaoh) in the 3rd miracle. At this point Moses is standing in front of the scrim getting ready to go into the wilderness for more instructions from God. The word “verbal” is appropriate in that the glib Aron is the master of ceremonies for the miracles:

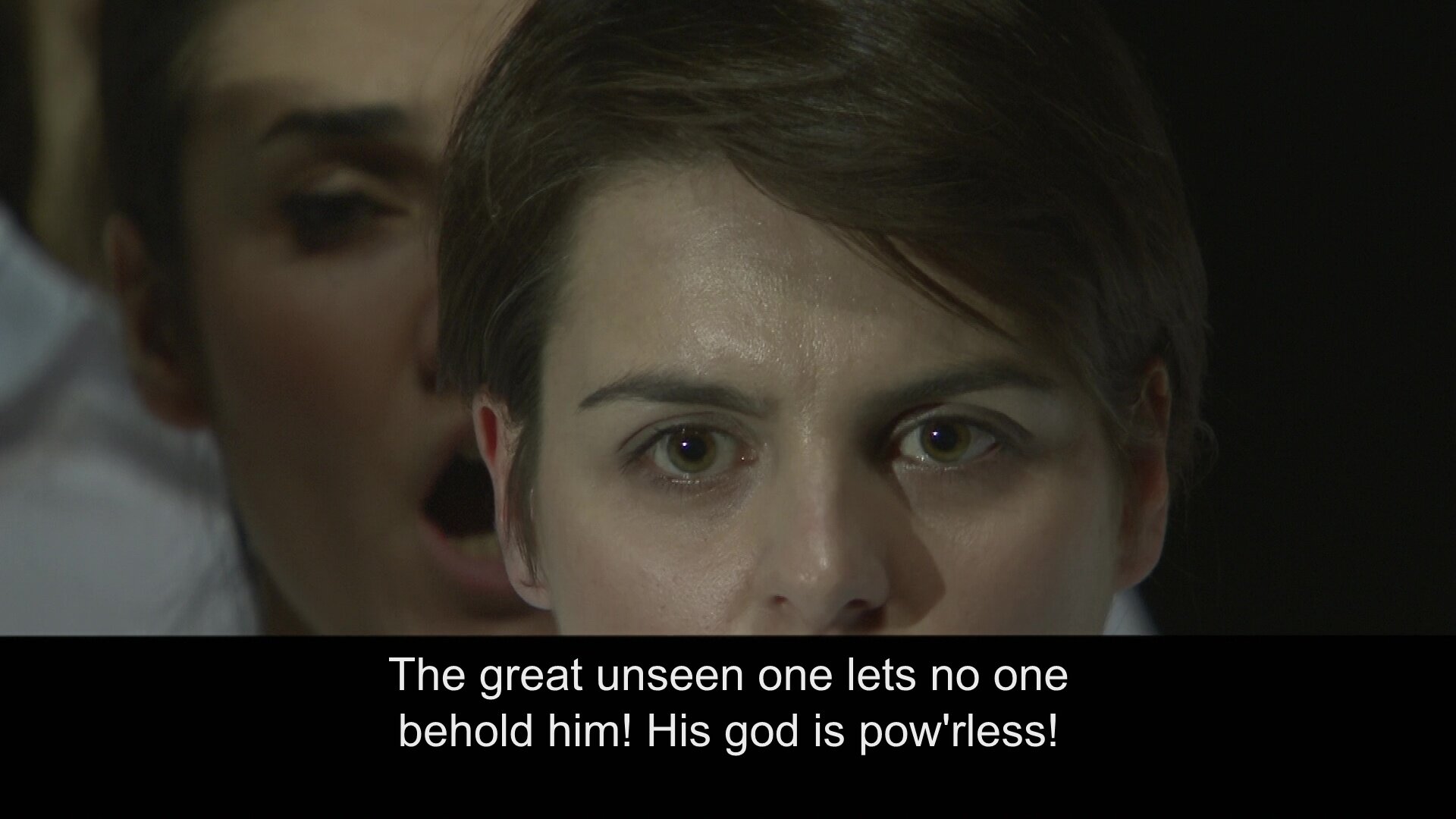

Moses takes his time. In Act 2 the white scrim is lifted. The people start getting nervous about this odd, unseen God that Moses knows:

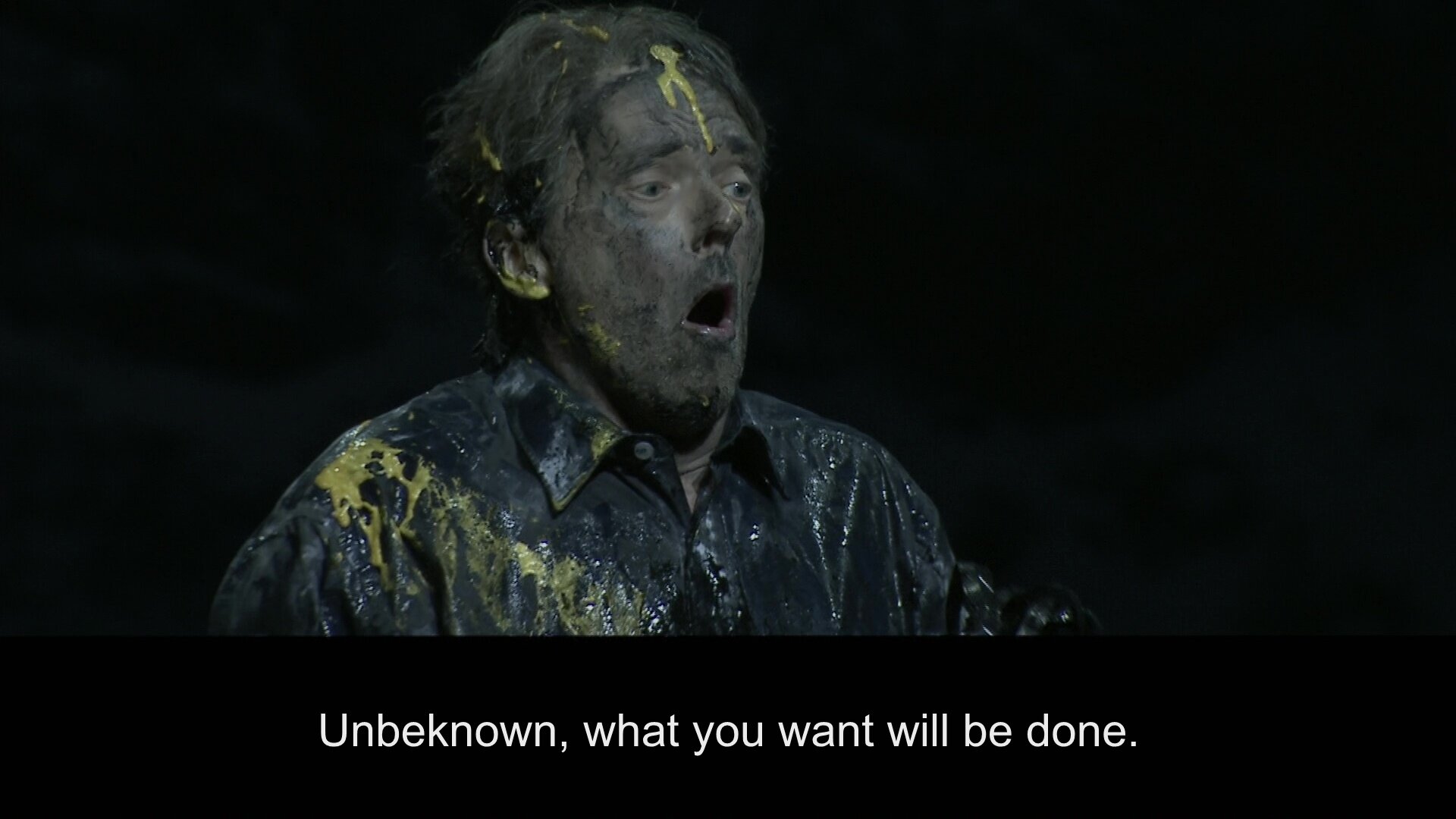

As we say in English, Aron now has “mud on his face” because Moses has been gone almost 40 days:

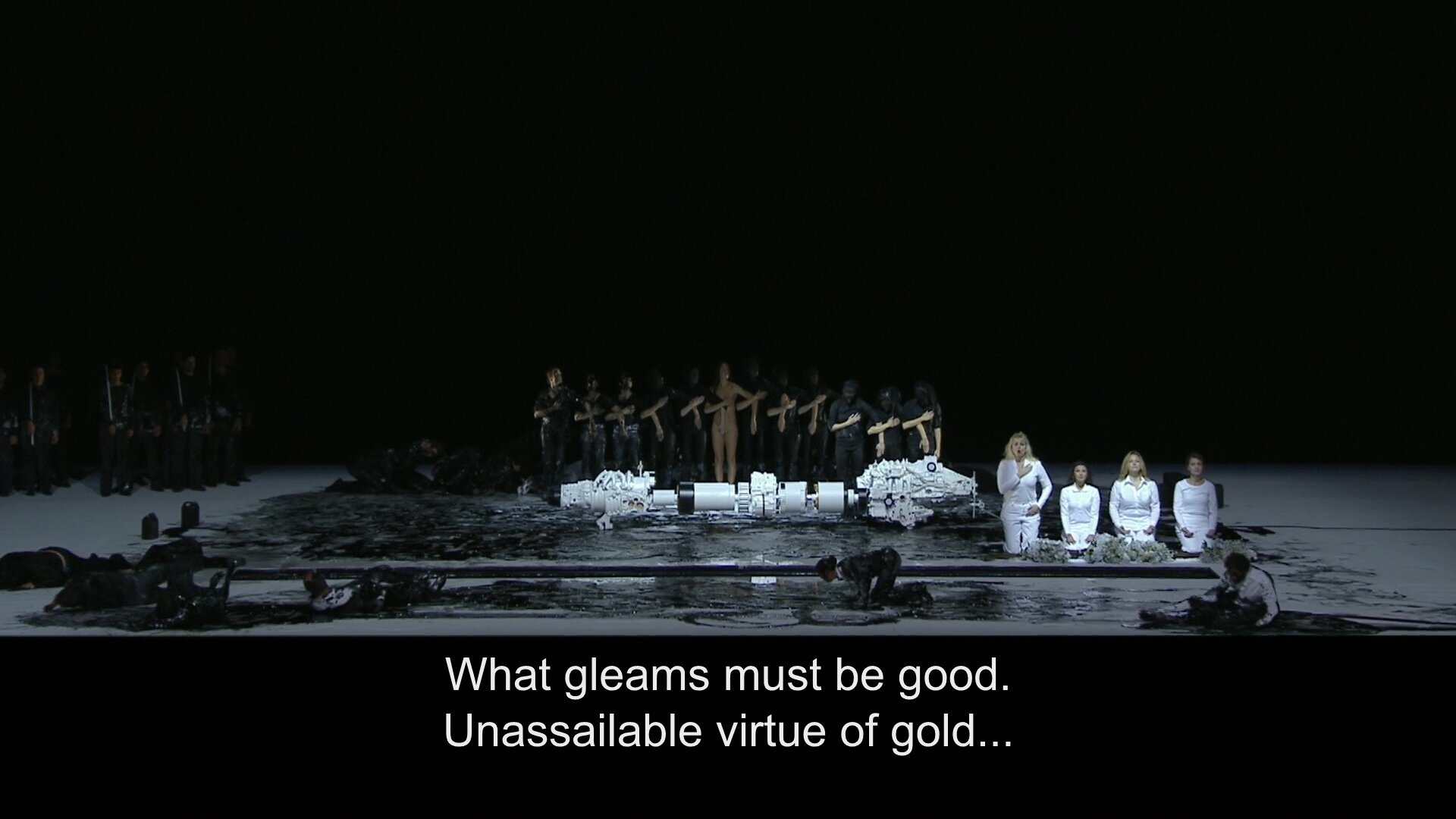

The people become disorderly and licentious. Aaron gives them back their favorite idol, the golden calf:

The enormous Charolais ox has become the most famous golden calf in opera. He’s been trained to enjoy dodecaphonic music and to ignore the woman. He has two handlers, but prudence requires that he not be kept on stage too long:

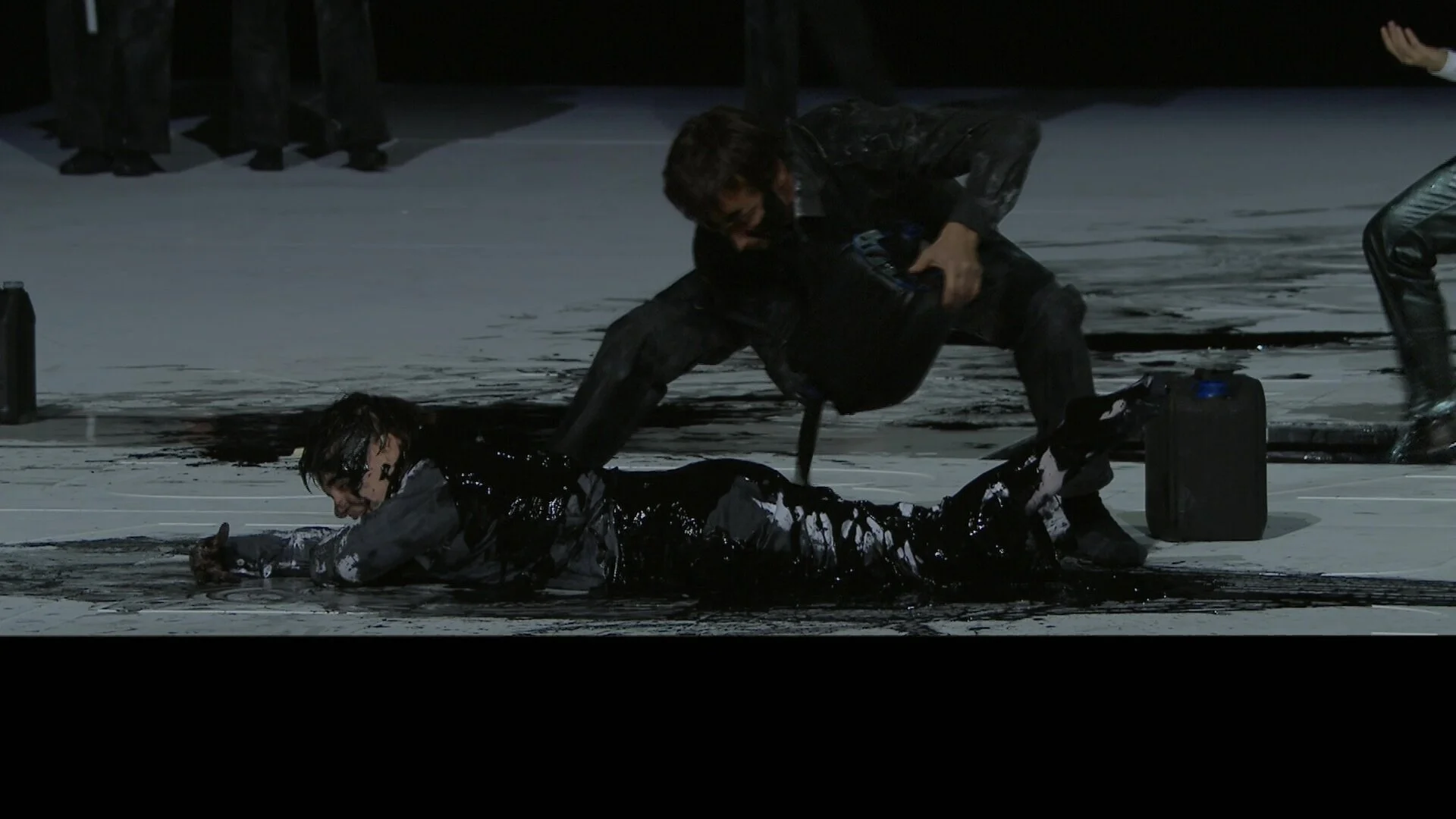

Next follows a long series of complicated orgies. You would need a score with the libretto to figure out the identity of all the characters Castellucci presents and who are given credit in the keepcase artwork. But all are sinners and deserve to get drenched in the black ink of shame:

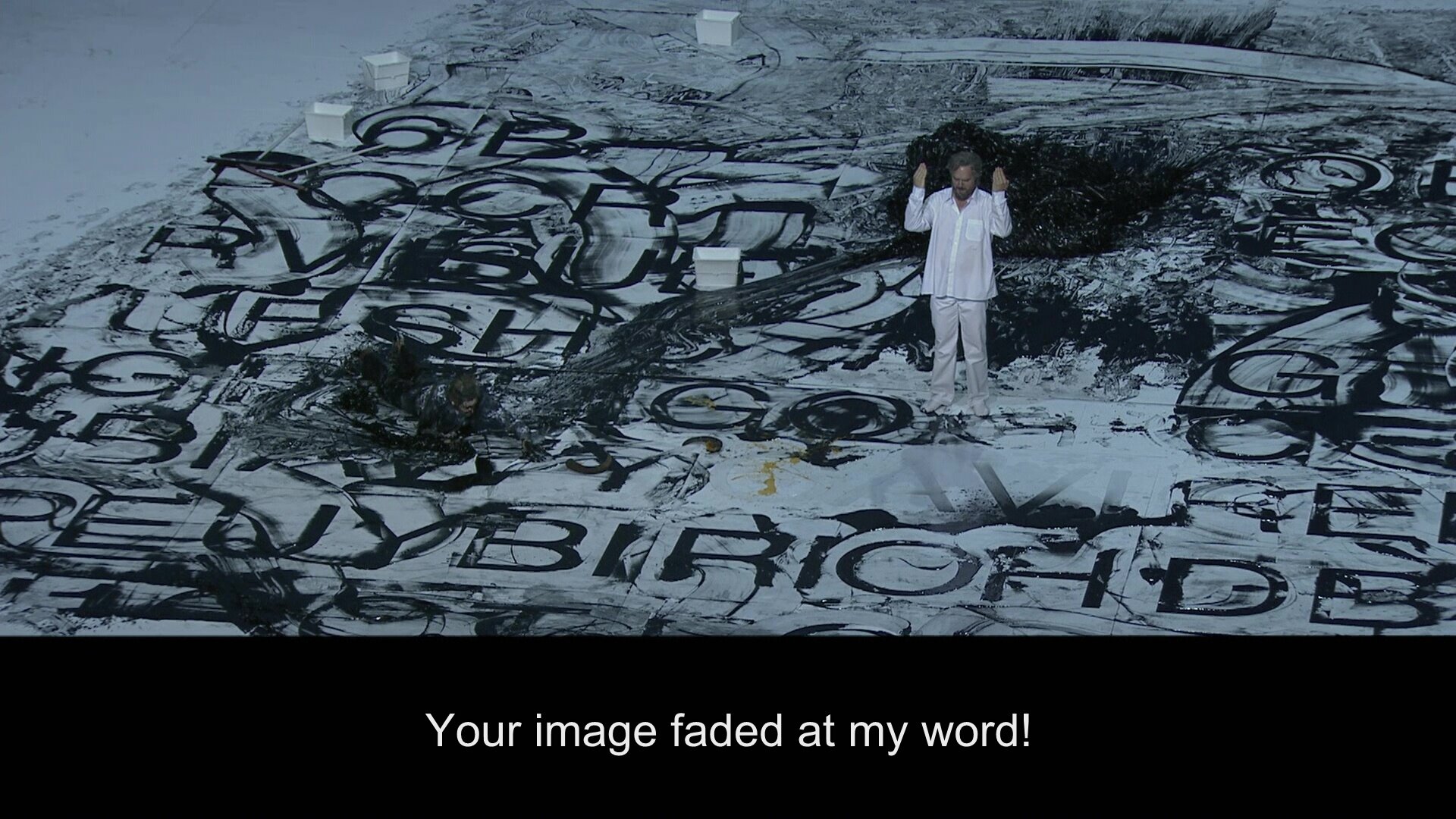

Castellucci is a grand showman and master of striking images. I also think he likes to throw into each production a “magic” stunt that makes the observer wonder, “How the heck did he do that?” Here, after creating a deep trench in the stage in which many chorus members are baptized in black stuff, we now see Nicky Spence pass through the trench as ein Junger Mann and emerge unblemished. How? Why? Well, never mind — he gets drenched in black later:

The climax of the the orgies is the sacrifice of 4 naked virgins shown in the next 3 screenshots below. I doubt that French law is involved, but it seems the Bastille management allows but one identifiable nude on the stage at a time:

The people are suffering from a terrible hangover, and Moses is still somewhere on the mountain. Aron has himself become a totem with a dress of magnetic tape and Oceanic mask:

Finally, after 40 days Moses returns. Ne xt comes an extensive philosophical and theological debate between Moses and Aron:

Moses’s tongue remains tied, but he has managed to bring the written word of God to the people. Moses wins the debate even though he breaks the tablets:

Schoenberg intended to write a third act to this, but he never got up the energy to do it. Perhaps he realized in time that the second act brought the work to a satisfactory end. And for viewers not used to dodecaphony, 2 acts is enough!

Moses here doesn’t sing; rather, he uses sprechstimme, a manner of uttering words promoted by Schoenberg that apparently has never been adequately defined and sounds to me like a singer with a sore throat talking as loud as he can. The chorus singers worked for a year to learn their long dodecaphonic parts. The chorus members are probably still talking about all that work leading to an ink bath! We have to assume that one of the best opera orchestras in the world working under Philippe Jordan himself must be playing the music right. In any event, SQ is fine considering the circumstances. And the producers went to great lengths to deliver good PQ in the home theater. Forming an opinion about the over-all quality of this production is probably above my pay scale, but I hope these humble words and screenshots give you an idea whether this title is a good one for you to puzzle over and enjoy. I give this title a combined grade of A and a ‽ designation as a warning.

Here are two clips that relate to the performance in Paris. There are other clips on YouTube from the later, but similar, performance with different artists at the co-producing Teatro Real in Madrid :

OR