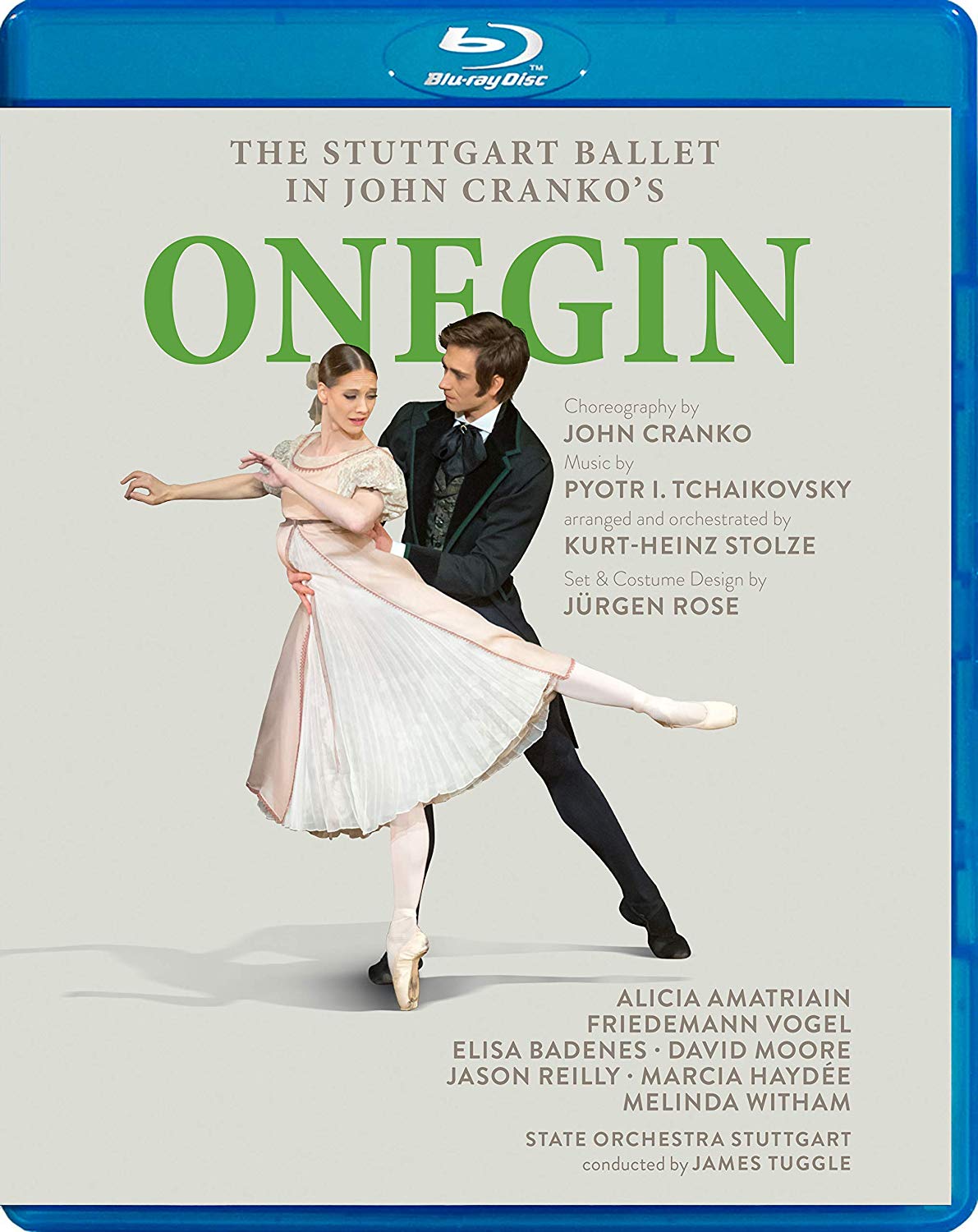

Onegin ballet performed 2017. Music by Tchaikovsky arranged and orchestrated by Kurt-Heinz Stolze (various selections but no music from Tchaikovsky’s opera Eugene Onegin). Choreography by John Cranko. Stars Friedemann Vogel (Onegin), Alicia Amatriain (Tatiana), David Moore (Lensky), Elisa Badenes (Olga), Jason Reilly (Prince Gremin), Melinda Witham (Madame Larina), and Marcia Haydée (Tatiana’s and Olga’s Nurse). James Tuggle conducts the State Orchestra Stuttgart. Set and costume design by Jürgen Rose; artistic supervision by Reid Anderson. Directed for TV by Michael Beyer. Recorded in 4K but published in 2K. Released 2018, disc has 5.1 dts-HD Master Audio sound. Grade: C+

Cranko introduced today’s Onegin in Stuttgart in 1967 (after revising slightly the original 1965 version). It’s an extremely simplified, straight-forward telling of the lost-love story from Puskin’s poem with elaborate but easy-to-understand dancing and acting in a naturalistic style (no pantomime). It was an immediate hit and has been in the Stuttgart repertory ever since. It was quickly taken up by many dance companies around the world. With the exception of the great Tchaikovsky/Petipa works from the 19th century (Sleeping Beauty, etc.), Cranko’s Onegin may well have been seen by more people than any other ballet. (After you watch subject title a few times, you will instantly recognize it in many YouTube clips on the Internet from other ballet companies.)

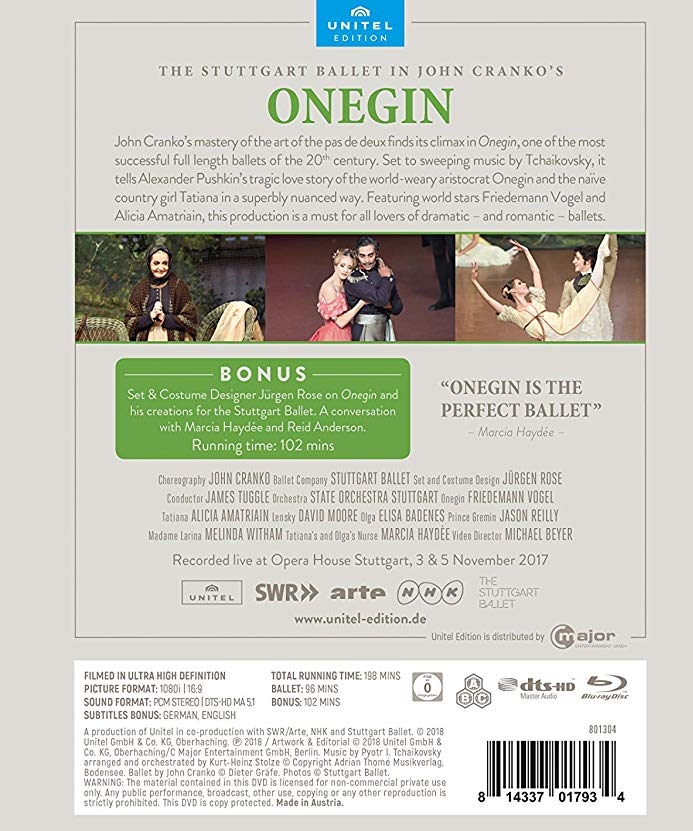

Cranko died in 1973 in an accident. But some of his colleagues from 1965 were still alive and working in ballet 50 years later in 2017! So the idea evolved to do a Cranko series of modern videos to preserve his legacy. Subject Onegin was the first title to be published followed by a Romeo and Juliet, which harks back to 1962. The main focus of these two titles is to show what these story ballets were like when they came out in the 1960’s. Even the package art work is deliberately designed to look old-fashion and “traditional.” (When we first saw PR about these titles, we thought C Major was starting a budget label featuring legacy material from a vault. But no, these are recent recordings in HD video of old works that have been in repertory for a long time.)

The ballet runs 96 minutes. There is also a bonus extra on the disc of a conversation among Cranko contemporaries that lasts 102 minutes.

In our initial screenshot below we see on the left Alicia Amatriain who stars as Tatiana in 2017. On the right is Marcia Haydée, who stars plays Tatiana’s Nurse. The amazing thing is that Haydée was the dancer who, when she was 50 years younger, originally created the role of Tatiana (in 1965)!

Jennifer Holmes, in Apollo’s Angels, her magisterial work on the history of ballet, laments that “the ballet repertory is notoriously thin” (Introduction, Page xx ). Most of the ballets of the past have been lost forever because there was no way to record them for future use. But now there is a way with HD video to document works to be revived long after the original participants have died (assuming you can preserve the means with which to play back the videos). And Haydée is not the only player who assures us that what we see in this video is historically authentic—in the bonus extra the original set and costume designer, Jürgen Rose, talks (a lot!) about how it was back then. One has little doubt that the old chair in which the nurse is sitting above is the exact same chair that was used in 1965 and which has been stored in the props warehouse ever since.

But, alas, there is a downside to this historical focus. Things that looked fine to audiences in 1967 don’t always look good to the HD cameras today. In the next screenshot below, we see, from left to right, Melinda Witham as Madame Larina, the nurse, Elisa Badenes as sister Olga, and Tatiana. On a big TV screen, this image presents difficulties: we believe there are three scrims supporting set paintings at different distances and together the scrims generate a shimmering and distracting moire pattern:

And in the close-up of the garden table below, the nearest scrim becomes painfully obvious:

Next below is a whole-stage shot in which the scrims are no longer discernible. This is a gathering of the local peasant girls for folk dancing. Their costumes look to be in good repair, but the pastel look is too sentimental and dated:

Friedemann Vogel arrives as Onegin. In close-up the set looks crude or, perhaps, like some kind of modern abstraction. All the dancers in this show are excellent—Vogel strikes us as being incomparable in this role:

The letter scene. At this range you need a flame, not an electric bulb. And Tatiana’s love letter is about a paragraph long. In the poem, this letter takes her all night to write. It has in Russian literature roughly the same exalted status that the “To be or not to be” soliloquy has in English. Tatiana is not a flighty airhead (like her sister Olga). Tatiana is a young woman (however unworldly) capable of expressing profound motives and feelings, and this image at close range doesn’t get this across:

In the next 2 shots below we see large-scale views of Tatiana’s name-day (birthday) party. The ancient set is marred by horizontal stripes which are (we think) folding creases or discoloration caused by backing material. The set canvases have deteriorated to the point that you can frequently see through them and see dancers moving behind them on the way to their entrances. Overall the set has a sad, dilapidated aspect that is likely invisible to the people who have been living with it or 50 years:

And in this view the set looks positively shabby. Sorry, this will not do;

Below more shabbiness, and what a vile yellow!

Murderous scrim and moire effects in the next two shots below:

And here, of course, is the death by duel of Lensky, sister Olga’s sweetheart. After this tragic event, Onegin flees into voluntary exile for a number of years:

Cranko’s choreography is delightful throughout and is, of course, the reason for the great popularity of this show. Next below we see the grand ballroom scene, again overloaded with pastels. Jürgen Rose is justly proud of his many contributions to sets and costumes of the Stuttgart ballet. But if you are going to make an HD video, the sets for this Onegin are way past their useful life and need complete replacement. The costumes are in somewhat better condition, but still look dated to us. For a better understanding of the need to update the costumes, check out the pastel-based designs of the Royal Opera House Sleeping Beauty from 2006. Then look at the updated designs for the same production recorded in 2017. The old pastels have been replaced with deeper, more vibrant colors and somewhat simpler lines for clean, fresh-start look. Why has the Stuttgart company not updated its Onegin? Maybe they don’t have the resources to stay competitive. Or maybe the company has become a kind of museum, stuck forever in the past:

There is also much effective acting by the stars in this cast. Next below we see Tatiana after her introduction into high society in Moscow and her marriage to Prince (and General) Gremin. (Cranko has Gremin show up at Titiana’s name day party like an old family friend. We think this is a mistake. In the poem, years pass after Onegin flees the country. Tatiana moves a 1000 kilometers to Moscow and steps up her game tremendously from her days of obscurity on the remote country estate. She meets Prince Gremin in Moscow, and her marriage to him propels her to the top of the Russian aristocracy.) Pushkin explicitly states (Chapter 8, Stanza 15) that Tatiana is not a striking beauty. Her appeal comes less from physical appearance and more from her purity and serenity of feelings, nobility in carriage, and confidence in her ability to empathize with others and respond appropriately—traits which, from the time of Pushkin on, are aspired to by every girl who wishes to be an ideal Russian woman:

Now it is time for Onegin to write a love letter to Tatiana! Tatiana knows that Onegin is coming for her, sooner or later. When her husband leaves for the field, he is astonished by the fervor of her goodby:

Below more fantastic choreography and acting as Onegin and Tatiana meet again:

Tatiana still loves Onegin, but she chooses to honor her marriage vows:

Every great ballet is based on great music, and that music must be well-played. The Tchaikovsky selections arranged by Kurt-Heinz Stolze have been good enough to support this show in some 35 different ballet houses. The music on subject disc is basically quite adequate. At curtain call time, James Tuggle appears on stage in tails and makes the traditional conductor gestures of gratitude to the orchestra. But there is no orchestra in the pit. Throughout the whole ballet, all the video is made from the front edge of the stage to the rear. There is never a shot of any musician. During curtain calls, Michael Beyer does give us a few shots of of the stage over the heads of the audience, but at angles that show nothing of the pit. A woman in a shot of a balcony appears confused by Tuggle and stands up looking in vain (we think) for the missing band.

If you are producing a ballet video and there’s a live orchestra, you will naturally show off the musicians and the entrances of the maestro, etc. If you don’t show this, the HT viewer can only assumed that the music is recorded. There’s nothing wrong with using recordings even for a full-length ballet by a major ballet company. But we question whether it’s proper for the Stuttgart Ballet and C Major to claim “music by the State Theatre Stuttgart Orchestra conducted by James Tuggle” and then send Tuggle out in tails at the curtain calls when in fact there was only recorded music for the event. The Stuttgart Company must be strapped for cash if they can’t get their orchestra out for this grand 50th Anniversary performance before HD TV cameras.

Onegin is a three-act work with three complete changes of sets. Between the dancing, there are a number of “parade scenes” and intermezzos. Because the dancing is so chopped up, it would be hard to do a Wonk Worksheet of the whole show. So as a sample, we did a Wonk Worksheet of 7 disc tracks from Act 2, the birthday party. Alas, the sample suffers from rank DVDitis with a pace of about 6 seconds per clip and only 65% of the clips showing the whole bodies of the dancers. We are pretty confident that this is representative of the video content for the entire show.

Finally, we should comment briefly on the long bonus extra, an interview with Jürgen Rose, Haydée, and Reid Anderson (recently retired Artistic Director). Haydée, and Reid Anderson say next to nothing. The always out-of-control Rose delivers an astonishingly self-indulgent fire-hose account of his career playing the role of the hyperactive genius he always was. The focus is, of course, to glorify the past with no thought at all of the present or the future. No harm. You have been warned.

Now to a grade. We start with an A+. Let’s reduce to A- for the canned music. For the obsolete sets and costumes, we reduce to B. The DVDitis gets us to a C. O! ut of respect for the historical importance of this disc, we will bump the grade up to C+. We feel bad about this low grade. For certain ballet professional and fans enamored with the past this may be an essential recording. But we have the duty to warn ballet fans who are used to the best current work by the important ballet houses around the world.

The Cranko libretto and choreography is still completely satisfactory for modern audiences. So there’s plenty of room in the market for updated productions of this (at Stuttgart and elsewhere) that could earn A+ grades.

Maybe we have been too harsh. Well, here’s a nice official trailer. After reading our review and watching this clip, you should have no trouble deciding if this video will suit your taste:

OR