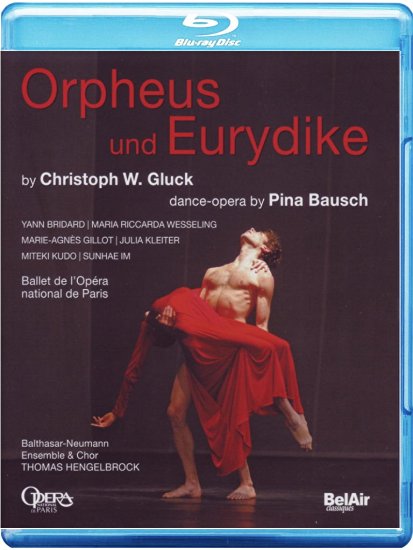

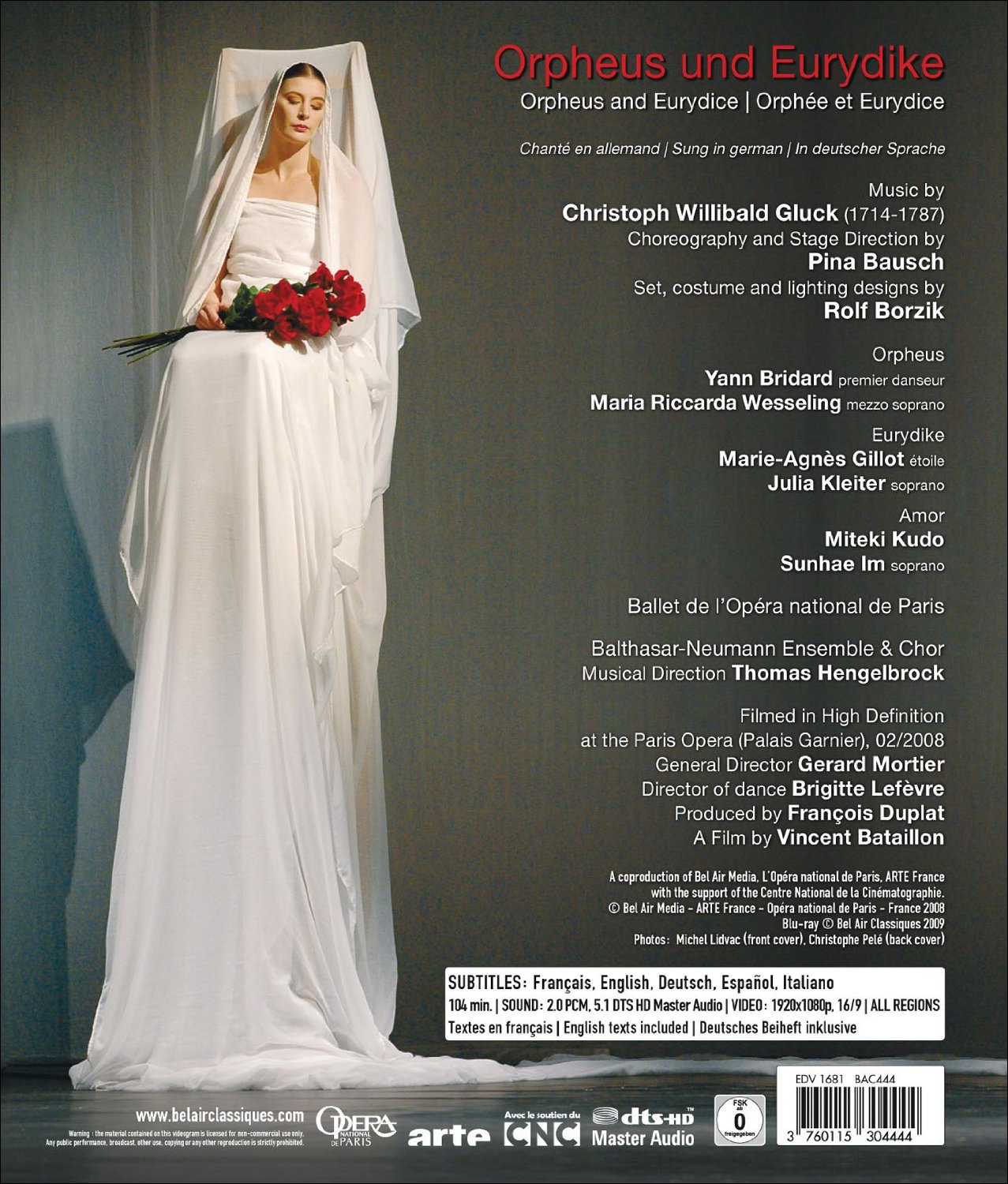

Christoph Gluck 💓 Orpheus und Eurydike dance-opera. Unusual choreography and stage production by Pina Bausch performed at the Palais Garnier Opera in February 2008. Singers and dancers appear simultaneously on stage for each main character. Gluck wrote Italian and French versions of his opera; this dance-opera version is heavily reworked by Bausch and sung in German. Choreographer assistants are Malou Airaudo, Mariko Aoyama, Bénédicte Billiet, Josephine Ann Endicott, and Dominique Mercy. Orpheus is danced by Yann Bridard and sung by mezzo soprano Maria Riccarda Wesseling; Eurydike is danced by Marie-Agès Gillot and sung by soprano Julia Kleiter; Amor is danced by Miteki Kudo and sung by soprano Sunhae Im. Also stars dancers Yong Geol Kim, Nicolas Paul, Vincent Cordier, Emilie Cozette, Eleonora Abbagnato, Eve Grinsztajn, Muriel Zusperreguy, Caroline Bance, Christelle Garnier, Alice Renavand, Amélie Lamoureux, Charlotte Ranson, Séverine Westermann, Natacha Gilles, Marie-Isabelle Peracchi, Bruno Bouché, Vincent Chaillet, Sébastien Bertaud, Alexis Renaud, and Erwan Le Roux. Thomas Hengelbrock directs the Balthasar-Neumann Ensemble and Choir. Set, costume, and lighting designs by Rolf Borzik (Pina's husband who died in 1980). Costumes made by Marion Cito; lighting by Johan Delaere; lighting engineers were Michel Susini and Madjid Hakimi. Directed for TV by Vincent Bataillon; produced by François Duplat. Sung in German. Released 2009, this disc has 5.1 dts-HD Master Audio sound. Grade: A+

The three main characters, Orpheus, Eurydike, and Amor, are sung on stage by opera singers and are also danced by leading members of the Paris Opera Ballet. The rest of the on-stage cast are ballet dancers. The chorus sings off stage. This unusual array of forces works well — it's a ballet show, but ballet and opera make roughly equal contributions to the overall effect. The music is original-instrument quaint. The dance style is "Tanztheater" modern, which, with it's relatively simple forms and use of repetition, meshes well with old music. Although the dancing is incisive, it is also elegant, smooth, tasteful, and profound. I watched the curtain calls. Orpheus (Yann Bridard), dressed only in dancer's briefs for every minute of the ballet, went off stage and returned with a woman in hand. I was touched by the sad tenderness and respect he showed to his companion — this is Bausch I thought. And when the camera then gave a close-up of Bausch, I thought,"Dear God! This poor woman looks ill." This production of Orpheus und Eurydike was filmed in February 2008, and Bausch died about 16 months later (June, 30, 2009) at age 68.

Actually, Bausch choreographed and first produced Orpheus und Eurydike years earlier when she was 35. Her husband, Rolf Borzik, designed the set, costumes, and lighting. Borzik died a few years later. Bausch dropped Orpheus und Eurydike from her repertoire. She went on to do many hard-edged controversial and iconoclastic productions which made her famous in the world of modern dance and an icon of modern culture in Germany. In a sense, the revival of Orpheus und Eurydike is a memorial for Borzik, whose work, but for this recording, might have been forgotten. It could be that Bausch was also writing her epithet with this revival.

Most of Bausch's work was done with her own dance company, Tanztheater Wuppertal, which is still active and is featured in the Wim Wenders movie Pina. Here the performance was given by the Paris Opera Ballet. The dancers had to master Bausch's style to perform this piece. It seems Bausch was personally involved in this along with 5 dance assistants who are credited above! The dancers did a splendid job of learning Pinaforma; the intensity and reverence with which the dancers handle their roles show how highly they regarded Bausch and her deceased husband.

Bausch divided her dance-opera into 4 parts that roughly correspond to the Gluck libretto:

Trauer (Mourning or Deuil), which begins after the death of Eurydike with powerful, rolling expressions of grief.

Gewalt (Violence), which expands tremendously on the role of the Furies in a stupendous surreal battle scene followed by capitulation to Orpheus.

Frieden (Peace or Paix), which consists mostly of sublime movements of the female corps. When younger, Pina was herself an incomparable dramatic dancer; I think each member of the corps was trying to be her worthy successor here. Now that Philippina Bausch is gone, I feel I see her dancing in this movement.

Sterben (Death or Mort), which show the second death of Eurydike and the determination of Orpheus to follow her.

First below is a screenshot from Part 1, Trauer. Mary-Agnès Gillot, the dancer portraying Eurydike, is sitting on the tall chair as the corps mourns her death:

Dancer Yann Bridard portrays the despair of Orpheus:

Miteki Kudo, dancing as Amor, reveals that she can help Orpheus bring Eurydike back:

Next below we are in Part 2, Violence. The gates of the underworld are fiercely guarded by Cerberos, who had three dogs' heads. In the background is a Fury reaching for an apple, but she will never grasp it. (Translation: " then the gate is guarded by Cerberos."). Screenshots can't begin to get across the impact of this long, complex, and frantic movement:

Still, Orpheus wins over his opponents. The woman in black on the left is Maria Riccarda Wesseling, who sings the role of Orpheus. Next to her in white is dancer Alice Renavand, a Fury, who is singing with the chorus as she dances (I doubt this was in the script). Later we will see the singers acting and moving about like dancers. (Translation: [he] awakens our sympathy.):

Now we are in Part 3, Peace. Having passed through the fearful gate, Orpheus discovers the blissful existence of the shades:

Eurydike emerges from the company of the blissful spirits:

Part 4, Death. Eurydike follows Orpheus but complains, "You shun (flee) my glance?":

Worn down, Orpheus looks at Eurydike. The blond on her knees is Julia Kleiter singing the role of Eurydike. She also begs for a glance from her singing Orpheus in black:

Now Eurydike is dead, represented by dancer Gillot and singer Kleiter in a heap on the stage:

Orpheus cries, "Woe, that I am still on earth":

Orpheus surrenders to the Cerberos:

Pina Bausch joins the curtain call and stands with Yann Bridard and Maria Riccarda Wesseling to our right. Note Wilfried Romoli is the Cerberos Dog's Head on our far left. He is not seen in the main show or credited on the package, so Pina's curtain call was added to our show from another recording:

Here's my original summary from several years ago: This is one of the very best HDVD titles we have. It combines the ancient pathos of the Gluck opera with the psychological brilliance of dance rooted in present culture. There are no technical issues to fret about. I never tire of watching this recording, and I know of no other fine-art HDVD title more worthy of an "A+" grade.

[Now follows new material dated September 30, 2016]

In my original summary I said "I never tire" of watching this Orpheus und Eurydike ("O&E"). When I first wrote this, I thought I was just using a cliche to show admiration of the subject matter. I didn't realize then that what I wrote was literally true. Let me explain.

Using old motion-picture terms, we call a video a "film" that normally consists of a string of individual "clips." The retina of the eye sends to the brain a continuous stream of electro-chemical signals about the light coming from the clips. The brain must constantly organize this stream of signals in a way that gives its person useful information about what is happening out there in the real (and very dangerous) world.

Let's say a person is watching a video of a symphony concert. The current clip shows 3 trombones playing. The brain knows the bones are usually in the right-rear of the orchestra. But when a new clip presents itself, the brain must say, "Where the hell am I now? Oh, that looks like a close-up of a flute. I must be on my knees in the middle of the front-center of the band." This task in not extremely hard because the brain already knows a lot about symphony orchestras, and the brain is somewhat relaxed because symphony orchestras rarely kill members of the audience. But making the transition from one clip to another does require the brain to invest energy in paying attention to "Where am I?". And anytime attention is devoted to "Where am I?", less energy is available to actually listen to the music.

Now let's suppose the video the person is watching happens to be the Mahler Symphony No. 1 published in 2011 as part of the "Keeping Score" series by the San Francisco Orchestra. That performance lasted 53 min. and 30 seconds (53:30). And as you can see for yourself from the Wonk Worksheet, there were 890 clips in the video of that performance! That works out to be a new clip on average each 3.6 second. The folks making this video thought they doing something brilliant by atomizing the video into an astonishing number of tiny views. There are even 210 clips showing nothing but close-ups of individual instruments! The video does succeed in forcing you pay attention to 890 different tableaux in less than an hour. But at the end, you may remember little about the music and you might well feel tired rather than uplifted.

Now why am I talking about a symphony video in a review of a ballet? Well, next let's compare a clip analysis of O&E to that of the "Keeping Score" Mahler 1. Now take a look a a new Ballet/Dance Wonk Worksheet filled out with a strict analysis of the number of clips in subject O&E. Even though O&E is 40 minutes longer than the Mahler 1, the O&E has only 46 clips!

It's a bit hard to grasp. 46 clips in the ballet vs. 890 in the symphony. An average clip time of 122 seconds in the ballet vs. 3.6 seconds in the symphony. Which video would you expect to be easier to watch? Do you see now why it's literally true that I "never tire" of watching the O&E?

I admit I'm not being fair. I'm comparing one of the worst symphony videos ever to maybe the best ballet video ever. But I think the conclusion is fair: the longer the average clip is in a video (i.e. the slower the "pace" of the video) the better the video is likely to be.

Let's look a bit closer at my strict analysis that there are only 46 clips in the O&E video. While literally true, this is a bit misleading. The strict view records only 1 full stage shot and 1 torso shot. But included in these 46 clips are quite a few instances where the camera zooms in or out to a different range at least briefly. So there is definitely more variety in the video that the strict analysis would suggest. To provide more nuance, I have to alter the definition of "clip."

The best tool we have for defining clips in a ballet film is the range of the image. This is because ballet fans generally want to see the entire body of the dancer. In a whole stage shot, the viewer always sees the whole body of every dancer. In a part stage/whole body shot, the viewer sees the whole bodies involved in the most important action taking place on part of the stage. But the TV director also may seek dramatic emphasis by reducing the range and using images that cut off feet or legs or even shows only a head, or feet, or perhaps just an eye. Some viewers like this "movie" approach. Others scream in horror because they have lost sight of the whole bodies of the dancers. So keeping track of the range of the images in a ballet film is essential.

In a dance film, the actors are constantly moving and the cameras are constantly following. Most of this motion is horizontal with the action moving back and forth in the same range of distance from the viewer. If I try to move my eye smoothly along a line of text in a book before me, I can't do it. The eye jumps in tiny twitching movements called saccades. But if I see a javelin thrown through the air or a dancer moving past me from side to side, my eye can smoothly and involuntarily track the movement. So I believe that following horizontal movement on a dance stage, whether by moving the eye or panning back and forth by the camera, is easy and natural. As long as the camera keeps the same range, I would not attempt to count as new clips any changes in the tableaux that arise as the images change.

Following the thoughts in the previous two paragraphs, I did a Dance Wonk Worksheet with a nuanced analysis and arrived at a total of 73 clips with 14 full-stage tableaux, etc. This yielded a pace of 77 seconds per clip and 87% of the clips showed the full bodies of the dancers. This analysis fairly and adequately describes the video content of O&E. It also continues to explain why I feel refreshed and uplifted by watching this dance performance instead of feeling tired and bleary-eyed.

So I'm happy to give O&E the first 💓 designation given on this website. This little icon is called a Beating Heart. This is, of course, a knock-off of the "rosette" designation Gramophone used in the past in its (now discontinued) Classical Music Guide. It goes beyond the A+ grade to say the title is of special importance and significance. In addition to an incomparable performance and excellent PQ and SQ, this O&E has exemplary video content provided by Vincent Bataillon. If a committee of wise men made an exhaustive study, they might conclude this O&E is the best fine-arts video ever produced.

OR