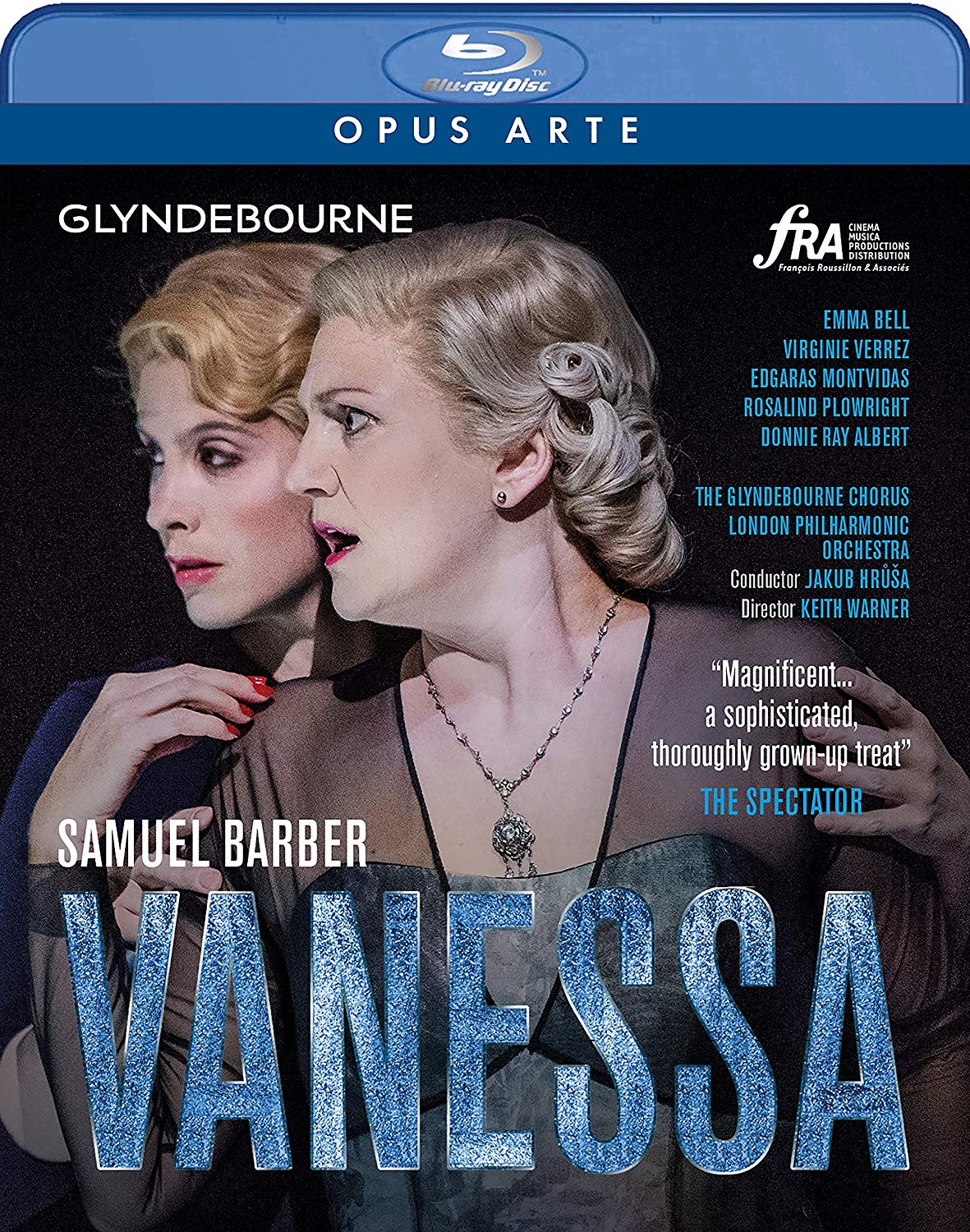

Samuel Barber Vanessa opera to a libretto by Gian Carlo Menotti. Directed 2018 by Keith Warner at Glyndebourne. Stars Emma Bell (Vanessa), Virginie Verrez (Erika), Edgaras Montvidas (Anatol), Rosalind Plowright (The Old Baroness), Donnie Ray Albert (The Old Doctor), William Thomas (Nicholas), and Romanas Kudriašovas (Footman). Jakub Hrůša conducts the London Philharmonic Orchestra (Leader Kevin Lin) and the Glyndebourne Chorus (Chorus Master Nicholas Jenkins). Designs by Ashley Martin-Davis; lighting design by Mark Jonathan; movement direction by Michael Barry; projection design by Alex Uragallo. Directed for TV by François Roussillon; produced by George Bruell. Sung in English. Released 2019, disc has 5.1 dts-HD Master Audio sound. Grade: A+

Written by two gay men, Vanessa is a womans’ opera that needs to be seen by men as well. It’s in part a work of symbolism (reminding one perhaps of Pelléas et Mélisande) and in part a social study of several generations of women (inspired perhaps by Ibsen’s Ghosts). Vanessa was written in 1958 and director Warner here sets it also in that time. The subject of Vanessa is the terrifying tension that existed then between the biological imperative to love and the existential fear of unwanted pregnancy. I grew up in that era and remember well the awful dread we all felt in an environment of social conformity with no sex education, no contraception, and no choice. (In those days, no unmarried girl ever had a baby. Sometimes a girl would get sick, go live with a far-off relative for a year, and then return as if nothing had happened.)

Vanessa is set in a Northern region of Europe where nobility still owned grand houses isolated on vast tracts of forest lands but also had access to fine, conservative fashions they could buy in the big cities. Below in our first screenshot are the women of our story, who live in not-very-cozy isolation with a few servants. Center is the old Baroness (Rosalind Plowright). Her unmarried daughter Vanessa (Emma Bell) is on the right. Erika (Virgine Verrez), a young adult granddaughter of the Baroness and niece of Vanessa, is on the left. Although the house is big, it is also claustrophobic because Vanessa has covered the pictures, mirrors, and window with curtains to slow down the appearance of her aging. Director Warner brought 2 huge mirrors forward. Behind the grayed out reflections from the mirrors we see scenes from the rest of the house, the surroundings, and the memories and thoughts of the protagonists. Glyndebourne spent a lot of money on these mirrors that pass stable images through with no wavering or distortion.

In our first screenshot below we see Vanessa reading a lament from the women’s favorite book, Oedipus:

The psychological temperature inside the house matches the brutal winter weather outside. For one thing, the Baroness has not spoken for years to her daughter, as the Baroness doesn’t talk to anyone whom the Baroness thinks is living a lie:

The warmest sentiment inside comes from Erika’s aria early in the show:

There is no man around other than servants. The only friend of the family is the Old Doctor (Donnie Ray Albert). He is a wise and forgiving person who has seen more than his share of human misery. He is still chagrined that the Baroness also will not talk to him (more on that below). You will probably notice that the Doctor is black. I’m pretty sure the libretto doesn’t call for that; rather, I think Albert won the audition. But once the black man was cast, director Warner got inspired:

In a flashbacks, we learn that the Baroness (a skinny blonde) has an intriguing back-story, we just never learn what it is:

Vanessa had a more conventional, if unfortunate, love affair with a handsome, cocky soldier named Anatol seen below (in Vanessa’s memory) preparing to decorate Vanessa with camellias:

In the very first seconds of the opera, Vanessa (a more voluptuous blonde than her mother) opens with a scream and then relives in memory her delivery of a baby, assisted by the Doctor, when they both were young (the actors playing young Vanessa and the young Doctor were not credited). Who was the daddy? Most likely the cocky Anatol. But the burning question is: What became of the baby? Some suggest that the baby, a girl, was spirited away until documents could be created to identify her as a niece named Erika. Others say that the baby was boy who was raised by his father Anatol. Both of these fates for the baby would turn out to be most unfortunate, as you will soon see:

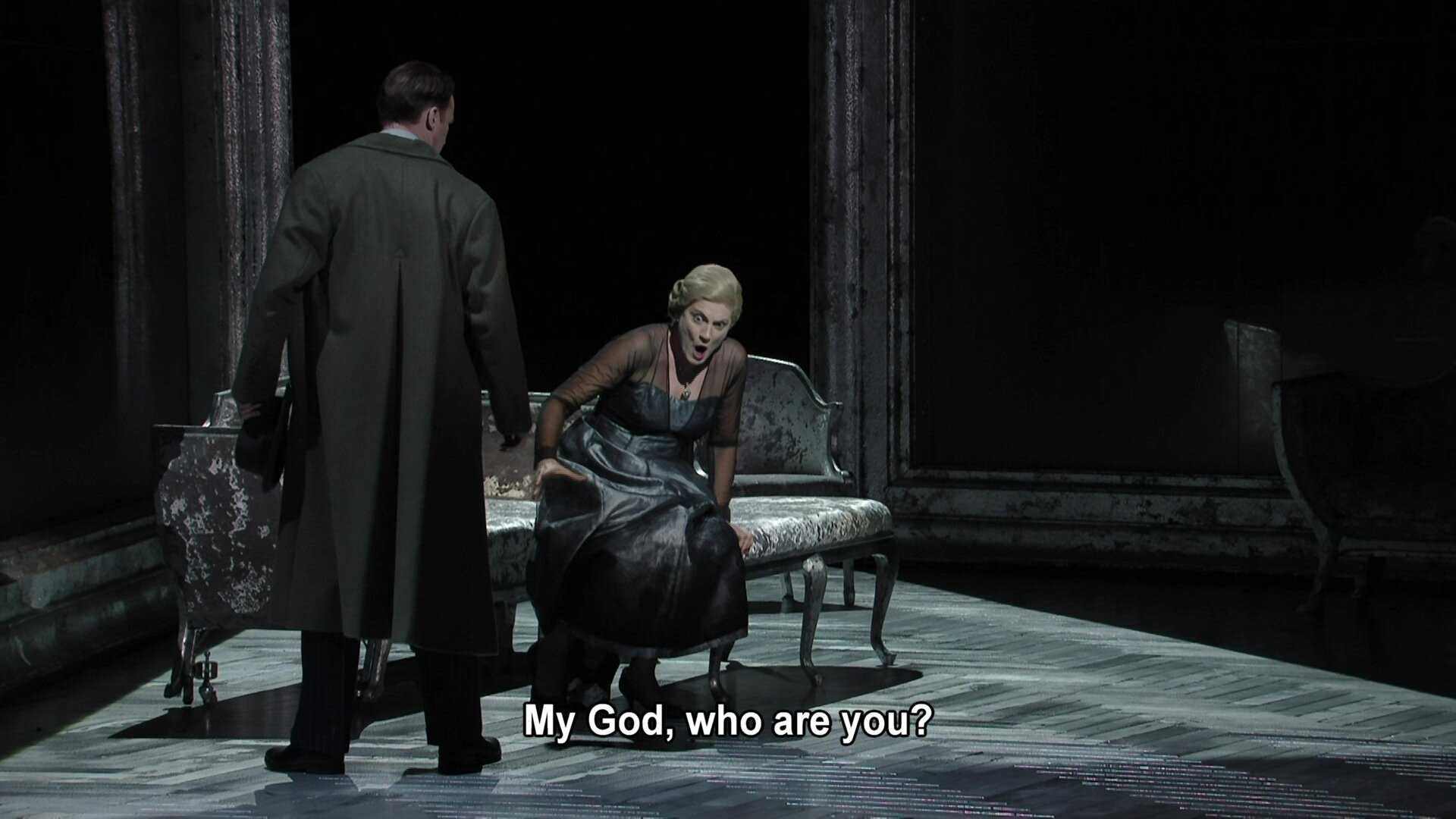

After Anatol decorated Vanessa with flowers, he left her. Twenty years then passed while Vanessa waited for his return. She did her best to preserve her youthful beauty. And then one day she learned that Anatole was coming to visit her again. On his return, she keeps her back to him until he will say that he still loves her:

Vanessa is astonished to hear Anatol say that he will try to love her and to discover that he is not the man who left her 20 years before. The man who got away was Anatol père. The man visiting is Anatol fils!

Anatol père has died. The goal of fils in his visit is to learn more about the wealthy woman his father had often spoken of and see if she perhaps would give him some money. But as Vanessa retreats in horror to her quarters, the false Anatol sees another target of opportunity: the love-starved Erika, who has already fallen for him on first sight:

There follows what might be the shortest seduction scene in all literature, but the seducer is Erika, not Anatol:

Erika reveals her infatuation with Anatol fils to the Baroness. Director Warner’s decision to cast the Doctor as a black man gives extra poignancy to her observation in reply:

Anatol fils offers marriage to Erika, but she is clever enough to recognize him for the bounder that he is:

In the meantime, Vanessa has recovered from the shock of learning that Anatol père is dead. She transfers her love from the father to the son!

H’m. If young Anatol is Vanessa’s son, then marriage to him is really improper, even if Oepidus is your favorite story! Or if Erika is Vanessa’s daughter, then we have mother and daughter both insanely in love with the same guy! If Vanessa’s baby was stillborn or was adopted out, then it would be a case of aunt and niece both in love with the same guy, which is bad enough. Either way, Erika, alone all her life, is dying of love. And her problem is now intensified because she has just realized she is pregnant by the man who will soon be her uncle:

Erika tries to kill herself. She is rescued, but she loses the baby and we can’t tell if she has a miscarriage or an abortion. Either way, the Baroness puts the blame on Erika and stops speaking to her:

Vanessa marries Anatol and they leave the mansion to live in Paris. Erika is left in charge of the estate and the care of the now increasingly decrepit Baroness:

The house is haunted by the ghosts of the earlier generation, and Erika is looking more and more like the old Baroness every day:

This is a show for the adults in your room. Although dressed as film noir, it is not a thriller, suspense, or horror story. It’s an intricate psychological puzzle involving extreme characters and situations, so I decided to focus most of this review on helping you prepare to find you way through the story. Once you get the structure of the work in mind, you will admire the clever libretto. Sorry if I spoiled anything. This was another triumph for Glyndebourne with astute personal directing by Keith Warner of an excellent ensemble of singing actors. The impressive staging by Ashley Martin-Davis with the see-through mirrors is supported by world-class lighting designs by Mark Jonathan and video projections from Alex Uragallo. And the sumptuous costumes and props add to the allure of the production. Finally, the video was made by François Roussillon with high quality jumping toward you from every frame.

Opera critics mostly loved this disc. Claire Seymour wrote a long and glowing review on operatoday.com. It got a Critic’s Choice Award in the January 2020 Opera News (page 50), and Fred Cohn wrote then that music director Jakub Hrůša “clearly believes in Vanessa, and this video will turn the viewer into a believer as well.”

Here’s an official Opus Arte clip:

And here’s a clip from Glyndebourne:

OR