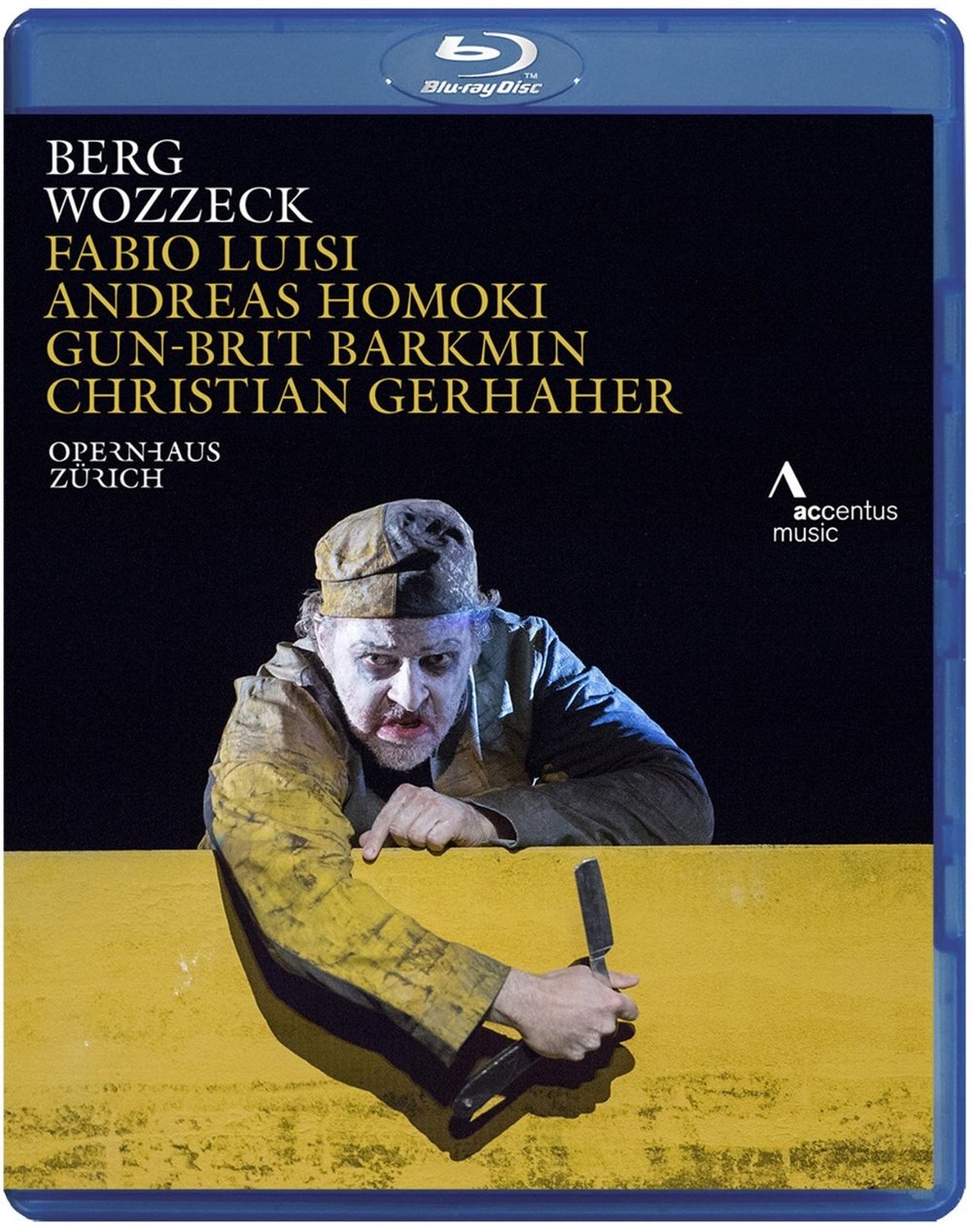

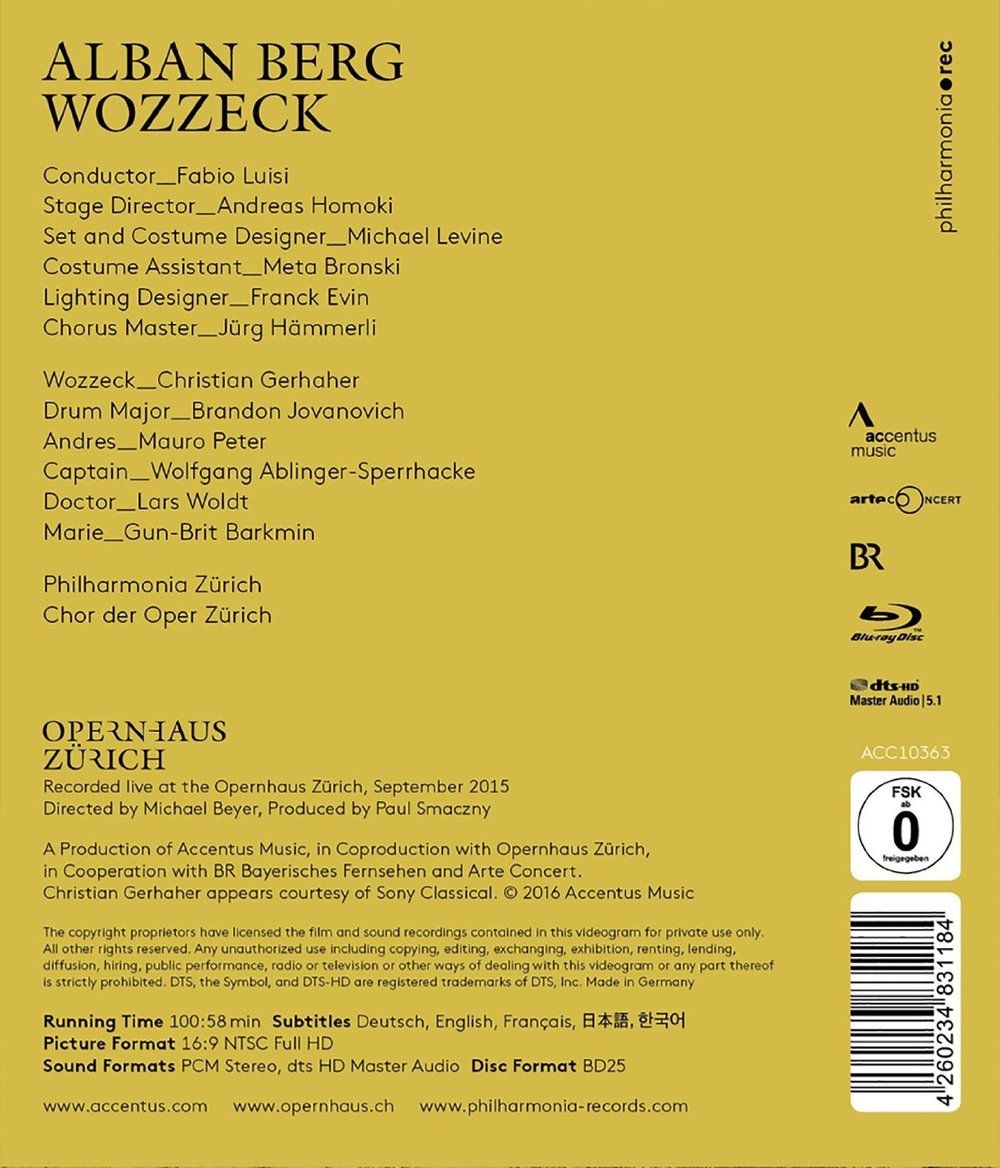

Alban Berg Wozzeck opera to libretto by the composer after Woyzeck by Georg Büchner. Directed 2015 by Andreas Homoki at the Opernhaus Zürich. Stars Christian Gerhaher (Wozzeck), Brandon Jovanovich (Drum Major), Mauro Peter (Andres), Wolfgang Ablinger-Sperrhacke (Captain), Lars Woldt (Doctor), Gun-Brit Barkmin (Marie), Pavel Daniluk (First Apprentice), Cheyne Davidson (Second Apprentice), Martin Zysset (Madman), Irène Friedli (Margret), and Alessandro Reinhart (Marie’s Child). Fabio Luisi conducts the Philharmonia Zürich and the Chor der Oper Zürich (Chorus Master Jürg Hämmerli). Set and costume design by Michael Levine; costume assistance by Meta Bronski; lighting design by Franck Evin; dramaturgy by Kathrin Brunner. Directed for TV by Michael Beyer; produced by Paul Smaczny. Sung in German. Released 2016, disc has 5.1 dts-HD Master Audio sound. Grade: A+

Georg Büchner died in 1837 when he was only 24! He was a member of the Young Germany movement and an active revolutionary who literally risked his neck and had to flee arrest by the secret police. He had published several well-regarded Sturm und Drang plays and a novella. He was a contemporary of Heinrich Heine; Nietszche was born about 7 years later. Büchner left behind 4 batches of barely legible fragments of a play called Woyzeck. It took specialists years of work to figure out that the fragments together formed a complete play. Woyzeck was first performed in 1913, 100 years after Büchner’s year of birth! Today Woyzeck is considered as the first modern play because it depicts the miserable life of a lumpenproletariat slob (rather than problems of an aristocrat). In our first sceenshot below, meet Woyzeck, or Wozzeck rather, as he is called in Berg’s opera (Christian Gerhaher):

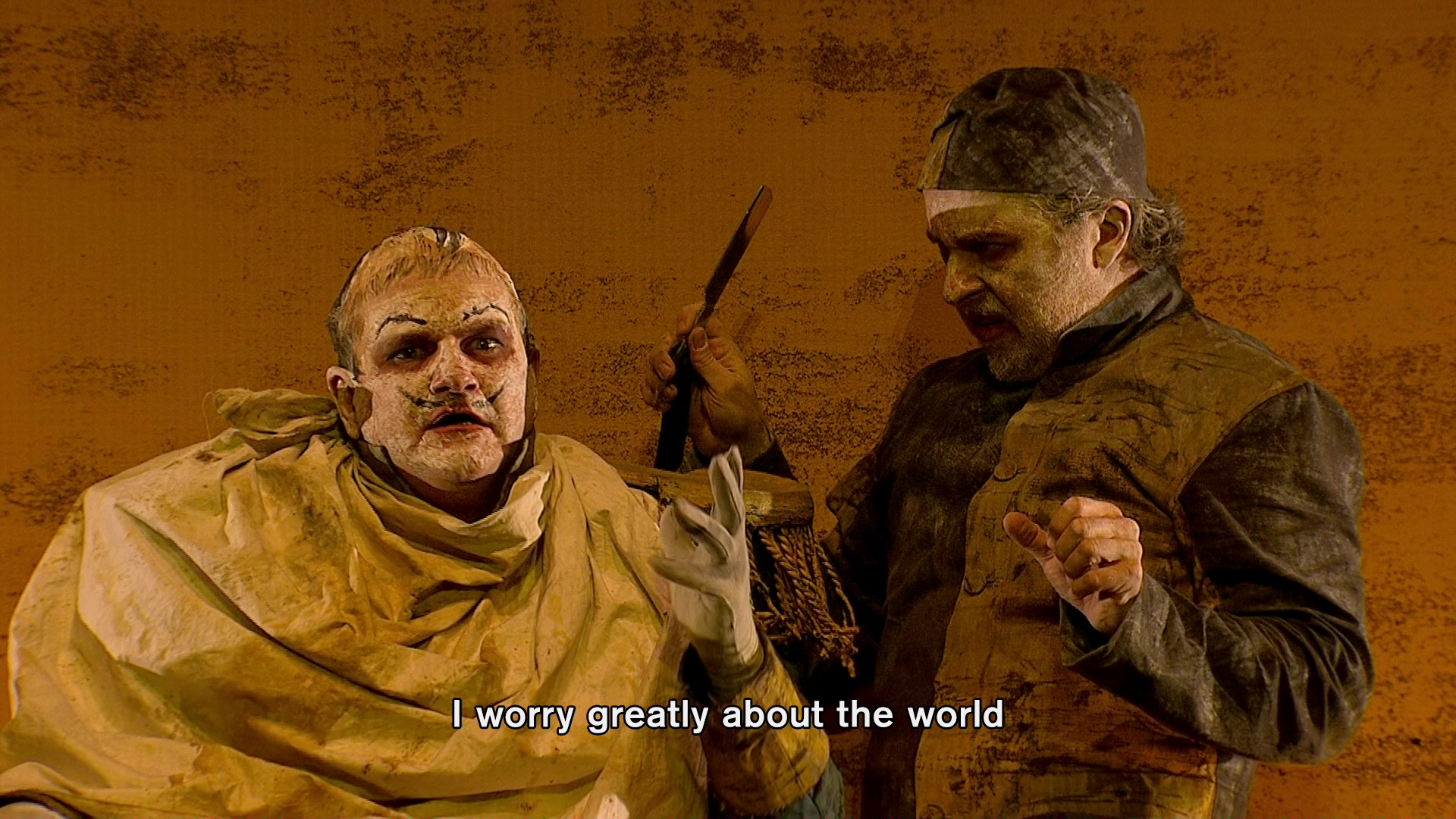

Wozzeck tries with little success to eke out a living shaving soldiers like the Captain, who berates poor Wozzeck for his lack of morals:

The Captain, who represents all authorities, says Wozzeck lacks virtue because he has a bastard son with Marie. Wozzeck replies that the basis for all morality is money:

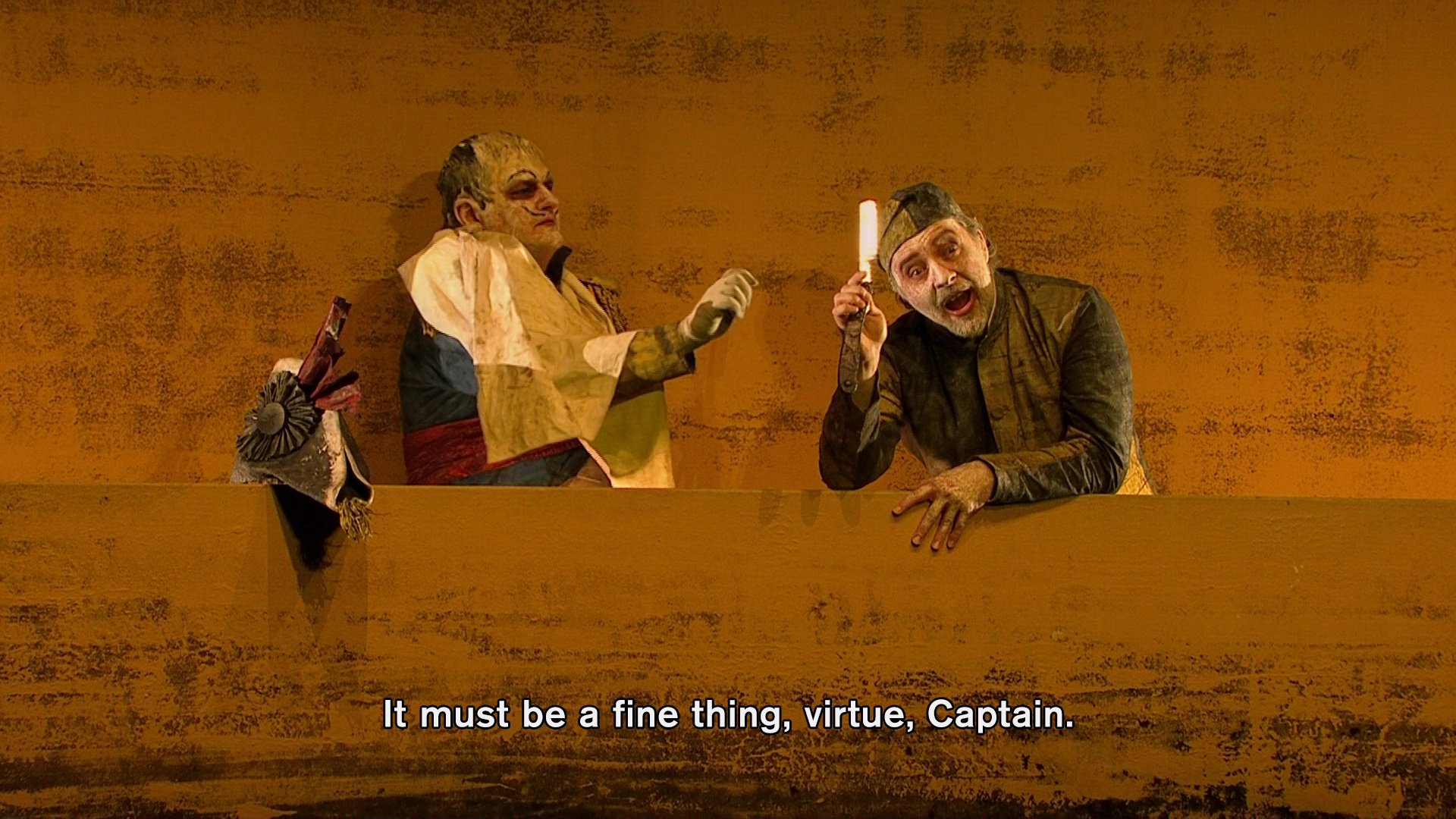

Wozzeck is also a victim of the mad Doctor (Lars Woldt), who stands for science and technology. In scenes of blackest humor mixed with shocking scatology (for literature written 1837 anyway) Wozzeck subjects himself to weird medical experiments to earn a few extra pennies. In the sceenshot below, the mad Doctor berates Wozzeck for relieving himself in a public place:

There is no “authorized text” for the play. We read an English translation by Rob Melrose (Exit Press, 2006) that would appear to be a sensible, “complete” rendition. We found little or no support in the Melrose version for the Doctor’s lecture on free will seen below, but there’s no doubt that Wozzeck is baffled by the mad scientist even more than by the Captain:

Were the people working on this in Zürich trying to make Wozzeck into an existentialist? No. There’s nothing like this in the Melrose test. And poor puppet Wozzeck is the opposite of the existentialist, who in all cases proudly asserts, “No excuses!”

But Büchner does (in Melrose scene 11) have the First Apprentice expounding on the wanderer standing in the stream of time and asking, “Why does man exist? The answer is, of course, more absurdity:

Although Wozzeck is baffled and oppressed by society, he is not without insight — he is a kind of mystic who stands for the psychological and emotional aspects of human experience. But overwhelmed by it all, he might remind one of a spring-driven toy that is being wound up ever tighter by fate:

Next below we meet Marie and Wozzeck’s son. Marie is an excellent mom:

Wozzeck gives Marie every extra penny he gets, but he still can’t support her and the boy. Marie is just as baffled by Wozzeck as Wozzeck is baffled by society:

Marie tries to upgrade with the strapping Drum Major, who claims to be a favorite of the Prince as well as the ladies:

Marie is all that Wozzeck has, and now he senses that she is slipping away also:

Wozzeck keeps hearing about Marie and the Drum Major. He feels the spring being wound ever tighter and tighter:

More philosophy:

Wozzeck and Marie go for a walk on the mysterious banks of the little river outside town. Marie is enchanted by the blood moon. Wozzeck realizes that the spring is as tight as it can be. In just a moment, the ratchet will break, and the spring will instantly release its energy:

As we briefly mentioned earlier, Büchner was about 100 years ahead of his time. His raucous, disjointed mosaic of 25 scenes (reduced to 15 for the opera) was written not in the German romantic style popular in 1820 but in a naturalistic or expressionist style. So it was not until the era of German expressionism in fine-art painting that Wozzeck got its premiere! With this in mind, it’s understandable how Director Homoki, his dramaturg, and the design team, came up with their astonishing mise-en-scène. We think they started off mentally with something impressionistic like the Van Gogh painting below. (The trees look like animals at the zoo or modern ballet dancers; was Vincent an impressionist or expressionist?) Notice the mustard color:

Next roughen things up a bit with something like “Portrait of a Woman” by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner (1880-1939). More mustard:

Turn to portraits for faces like this hallucinatory expressionist self-portrait by Emil Nolde (1867-1956):

Or this creepy self-portrait by Egon Schiele (1890-1918):

Or this lugubrious depiction of psychiatrist Fritz Perls by Otto Dix (1891-1969) — still more mustard:

Add a dollop of Max Beckman:

And finally top off with more ideas from Schiele — there’s still more yellow background, and do the white tones on the skin seem familiar?

Another brilliant stroke was the creation of the 6 independent frames which allow for fast scene changes (like location cuts in a motion picture) while institutionalizing the chaotic madness of the entire work. The frames keep surprising the viewer with their flexibility including their talent for tilting and dumping characters off the stage. It’s shocking the first time you see it, but you soon get absorbed in this grotesque world of bizarre characters slathered with face paint and dressed in crudely degraded costumes.

We haven’t said a word about Berg’s orchestra score or his writing for the singers. When this was first performed in 1925, the music was a tough task for everyone in the building. But that was almost 100 years ago now. As Fabio Luisi explains in the handsome keepcase booklet, orchestras and singers are used to modern music now and so is the audience. And the orchestra music would have to be as challenging as it is to match the evocative power of what’s happening on the stage behind the band. Or maybe we have that backwards — the designs have to be challenging to match the music.

The leading German opera magazine Opernwelt gave Christian Gerhaher its 2016 "Singer of Year" award for his portrayal of Wozzeck. In the December 2016 edition of Opera News, page 22, Adam Wasserman praises Gerhaher as one of the "most moving" singers in the world, and Gerhaher is quoted saying that Wozzeck is "one of the most perfect operas." William Braun writes in the April 2017 Opera News, pages 54-55, that "this is one of the best-sung Wozzeck recordings." Braun also approves of the set and concludes, "Everything demonstrates that Wozzeck is a truly great opera." Finally, Gramophone gave this its 2017 Best Opera Award. This is an obvious must-buy for contemporary opera fans. We can’t find anything to complain about, so we will give this an A+.

Here are two clips from this amazing show:

OR