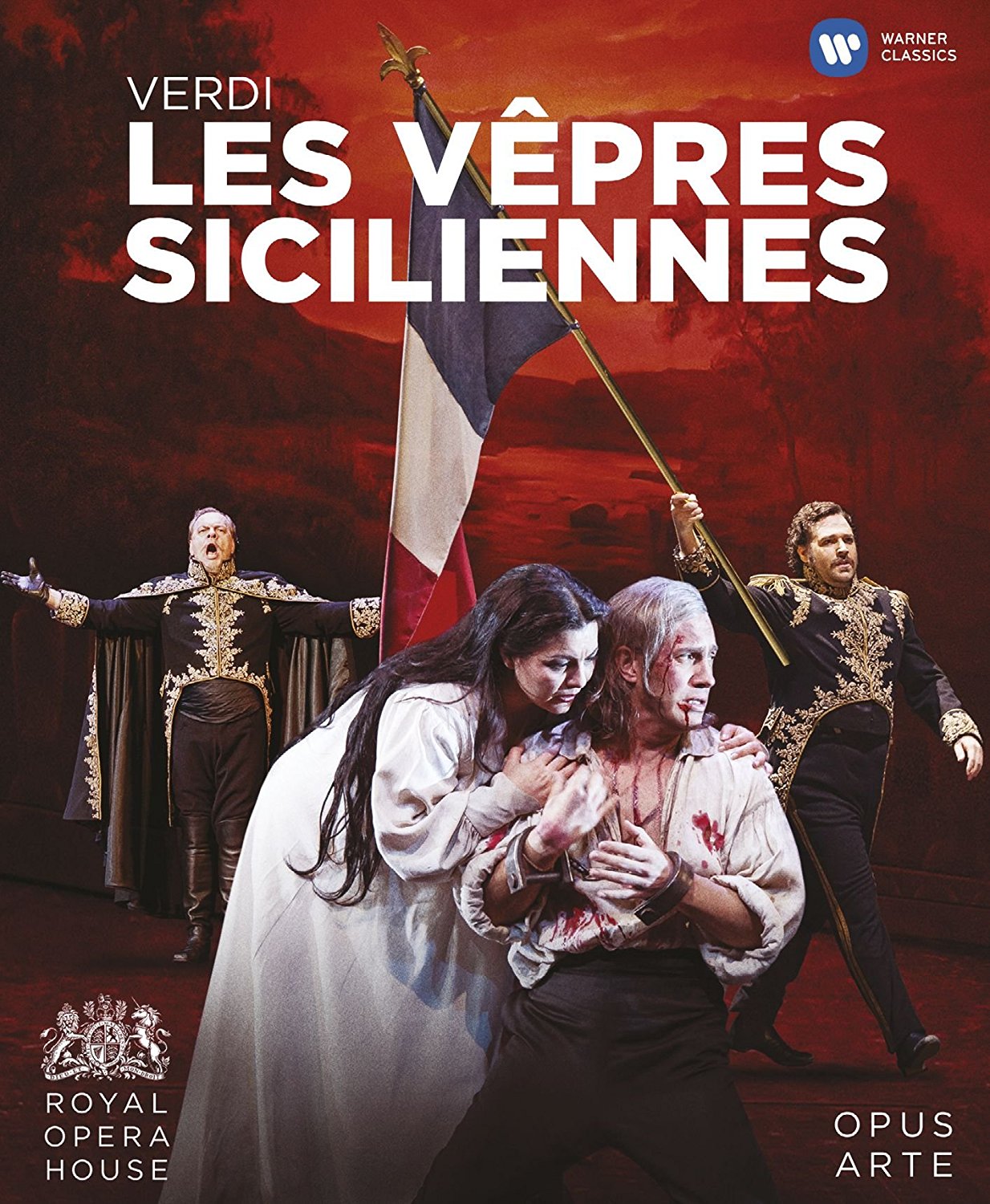

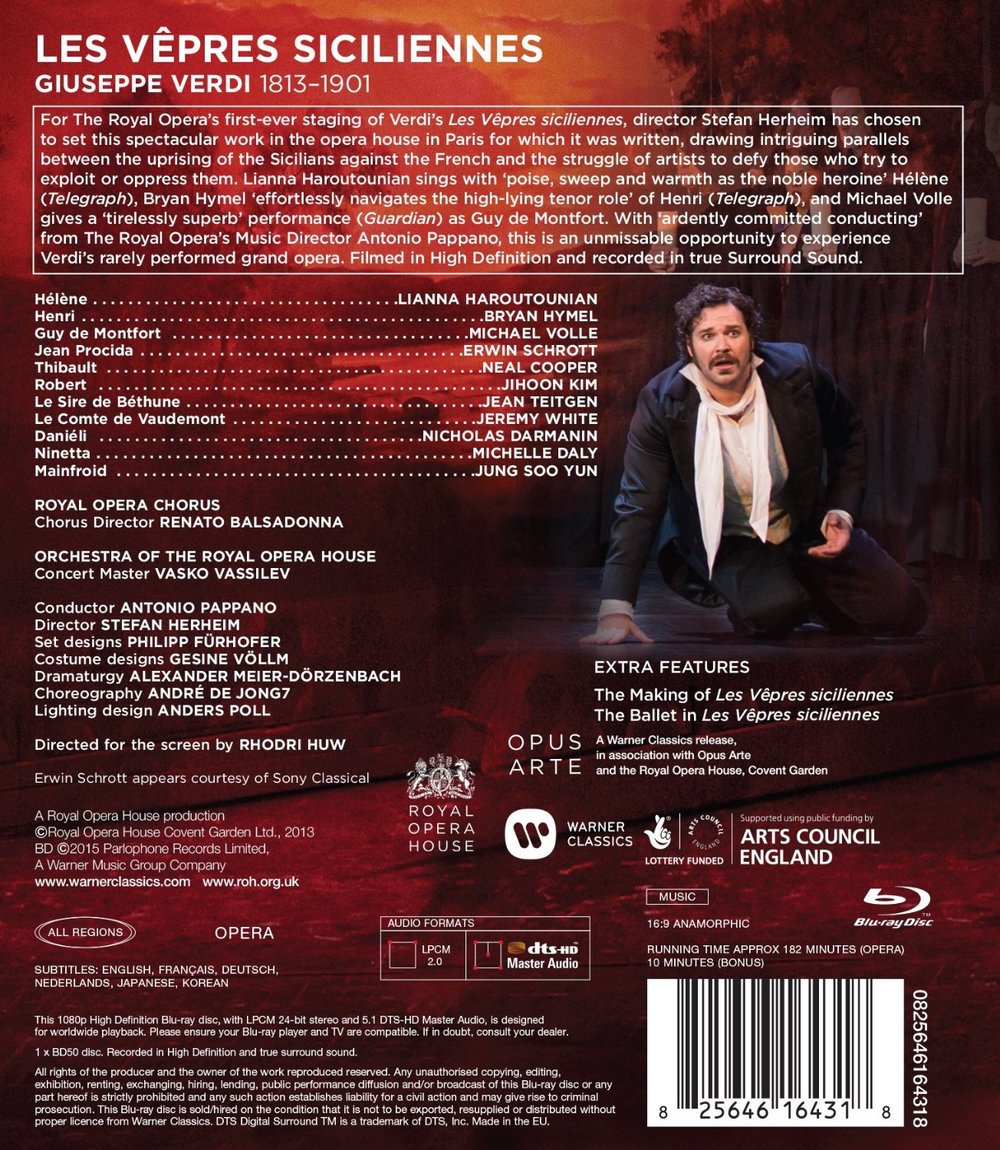

Verdi Les vêpres siciliennes opera to libretto by Charles Duveyrier and Eugène Scribe. Directed 2013 by Stefan Herheim at the Royal Opera House Covent Garden. Stars Lianna Haroutounian (Hélène), Bryan Hymel (Henri), Michael Volle (Guy de Montfort), Erwin Schrott (Jean Procida), Neal Cooper (Thibault), Jihoon Kim (Robert), Jean Teitgen (Le Sire de Béthune), Jeremy White (Le Comte de Vaudemont), Nicholas Darmanin (Daniéli), Michelle Daly (Ninetta), and Jung Soo Yun (Mainfroid). Antonio Pappano conducts the Orchestra of the Royal Opera House (Concert Master Vasko Vassilev) and Royal Opera Chorus (Chorus Director Renato Balsadonna). Set design by Philipp Fürhofer; costume design by Gesine Völlm; lighting design by Anders Poll; dramaturgy by Alexander Meier-Dörzenbach;choreography by André de Jong. Directed for TV by Rhodri Huw. Sung in French. Released 2015, disc has 5.1 dts-HD Master Audio sound. Grade: A

Les vêpres siciliennes is a French grand opera, an opulent, melodramatic genre that flourished and withered shortly before the American Civil War. Vêpres is considered by experts to be B-grade Verdi. This new production of Vêpres directed by Stefan Herheim at The Royal Opera played late 2013 to mixed print reviews. It came out in HDVD about 15 months later and immediately became a best seller! Why?

Herheim gives the HDVD opera fan (the kind with a HT and high-def TV) everything he could ask for. First, there's a real grand opera with lavish sets and costumes, a big orchestra, star singers, and double choruses portraying all the lugubrious, contrived, switch-back, high-drama situations that anyone could possible image or desire. Every twist in the plot is embellished with it's own glorious aria, duet, trio, quartet, or chorus number, all marching along in endless procession as midnight approaches. This is your money's worth. Second, for the younger set, Herheim provides a stylish update: instead of being set in the late-middle ages, the opera happens in 1850 in a Paris opera house. Third, for the intellectuals, there's a modern overlay with imaginary characters appearing throughout (such as a young boy in various costumes) which have meanings that are (usually) relatively easy to grasp from context (few Eurotrash-level mysteries). Finally, Herheim adds dancing whenever he can. Some of the ballet dancers do double duty as silent characters, and the chorus gets to do a lot of peasant dancing as well. (The Royal Ballet pulled out of this production on short notice, probably because its choreographer wanted to mount a discrete 40-minute show right in the middle of the opera, as was customary in Paris in 1850. Herheim then hired completely new free-lance forces to work under André de Jong, and the result is the best use of ballet in an opera that I know of.) So you wind up with more than your money's worth. Now to screenshots.

"The Sicilian Vespers" is the name (here in English) of a successful popular uprising by the people of Sicily against French occupation forces in 1282. Legend says John of Procida, a Sicilian physician and diplomat, led the uprising, which was signaled by the ringing of church bells at vespers on the Monday after Easter. Here we see Erwin Schrott as Procida, who has a ballet school at his palace. He's been reading in the newspaper about the French invasion of his country:

Guy de Montfort, the new French governor, heard about the girls at the ballet school. He and his men break in to rape them. Montfort gets first pick:

From this union a child named Henri Nota will be born. But neither Henri nor Montfort will know about any of this for many years:

The people of Sicily chafe under French rule:

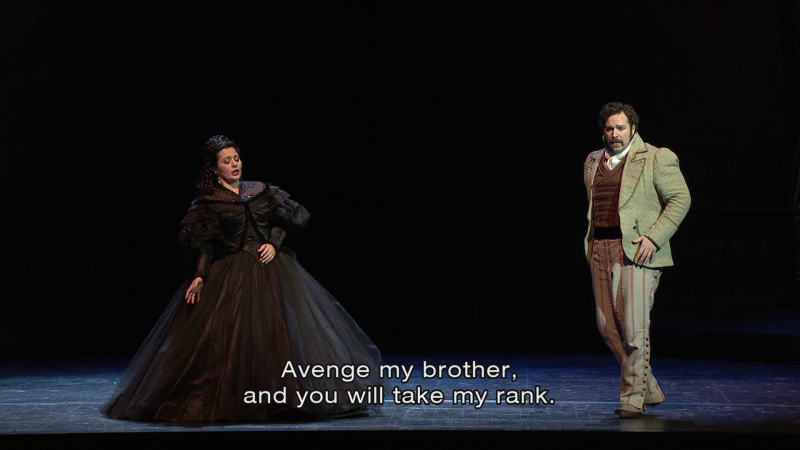

Lianna Haroutounian plays Hélène, a Sicilian aristocrat. (Marina Popslavskaya was scheduled to sing this, but Haroutounian became a real-life heroine when Popslavskaya called in sick.) Hélène's brother was recently executed for sedition, and Hélène is being held hostage by Montfort. But she is fearless in urging her people to resist the occupation (Hélène holds her brother's skull):

TV director Rhodri Huw injects a brief, extremely long-range "architectural shot" into the middle of his Act 1 video. This was a gutsy move that I don't recall seeing in any other opera video, and it works well in my HT. The stars and full Sicilian chorus on stage and the second French chorus in the (staged) opera house stalls create a wall of sight and sound that's impressive even from the rear of the Royal Opera House. This shot also reminds me somehow of all the work required to put on a opera and keep the audience comfortable and safe while it's running:

The fatherless Henri (Bryan Hymel) was raised by his mother as a revolutionary, and he is in love with Hélène. Seeking her out at Monfort's fort, he encounters the Montfort himself. The men seem intrigued with each other as Montfort warns Henri to leave Hélène alone and Henri boldly contends with the dictator:

Procida fled while Montfort sacked his palace. Now Procida has returned. The dancers in the next two shots are imaginary beings who, welcoming Procida back, stand for all the women of Sicily. Let's pause for a moment to consider Schrott's performance, which one print critic condemned as "preening." My friends, this guy can't help but preen. Everywhere he goes, women fall apart and turn into puddles. He preens when he brushes his teeth. If someone wrote an opera about Achilles, who else in opera could you cast for this other than Schrott? So if he will just show up, he's done what you pay him for:

Hélène knows a hungry winner when she sees one:

Meanwhile we see the cynical side of Procida. To stir up resentment in the Sicilian men, he encourages French soldiers to abduct the peasant brides at the annual mass wedding festival. This is a nasty example of ends justifying means!

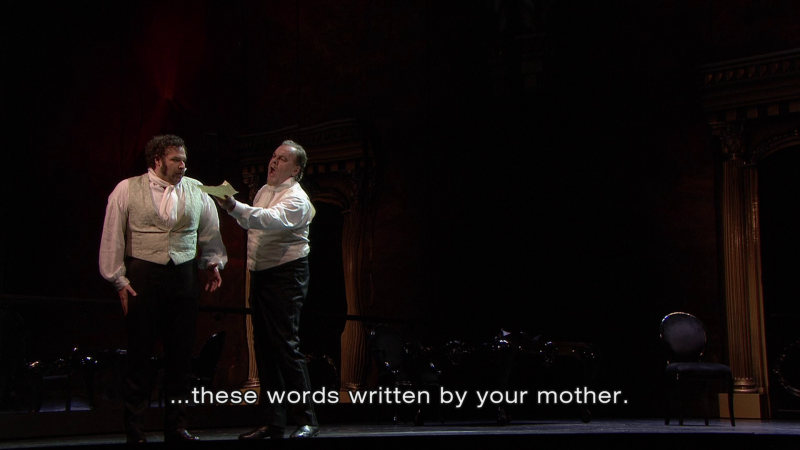

Henri's mother died. Her last act was to send a letter to Montfort naming Henri has his son and asking for clemency for him. Montfort reads the letter over and over as demon dancers and a young boy, all wearing skull masks, hover about:

Montfort, a bachelor, acknowledges guilt, at least to himself:

He sings a great aria about the loneliness of power and the emptiness of this life with no family:

Here are shots from the recognition scene:

The recognition scene ends with my favorite image from the opera—a glowing example of synergy of opera and dance:

Montfort attends a grand ball where a group of 14 revolutionaries, all wearing yellow ribbons, plan to assassinate him:

The conflicted Henri tries to warn his father to leave. Montfort soon catches on and the plot unravels:

Act 3 ends as Montfort quickly executes all the yellow ribbons (except Prosida and Hélène) in a scene that rings true for anyone who has been watching TV news lately:

Now Henri's friends hate him as a turncoat. This leads to a series of dramatic grand opera revelations and reconciliations:

Everybody wants to die:

Procida delivers an aria honoring all those patriots who have gone down in defeat for their country and have been forgotten even by their own descendants. Verdi was a politician himself and the greatest man in world history who happened to also be a musical genius. He's the only composer I know of who is honored as a father of his country. Verdi knew from person experience about the risks of tangling with censors and playing a real role in a fast-changing world. Every nation has a tomb of an unknown soldier; this aria is Verdi's tombstone for all the patriots lost to history:

Henri saves his sweetheart and Procida by calling Montfort, "Father." Montfort further directs the marriage of Henri and Hélène in a last-ditch effort to reconcile the Sicilians and the French:

This is a perfect solution for Henri:

Hélène hopes for the best:

There's delirious joy in the palace:

But in the countryside the people are ready to explode in rage. Procida isn't going to miss the opportunity fate has given him:

Hélène sees that Henri is doomed. She tries to stop the revolution by calling off the wedding in this scene with Procida dressed in black as Hélène's alter ego:

Montfort steps in and declares that Henri and Hélène are married. He next unwittingly commits suicide (and dooms his son) by directing that the church bells be rung—which starts The Sicilian Vespers.

In addition to his creative concepts, Herheim also delivers fine personal directing. The stars are all good actors and deliver good to great singing throughout. Pappano and Balsadonna are exciting Verdi conductors, and the Royal Opera House orchestra is excellent. The music was recorded well and is reproduced in fine surround sound.

So now you can see why this recording is a hit. Expert opera critic Mike Ashman, writing in the June 2015 Gramophone (page 95) declares this "hugely recommended." But Patrick Dillon in the July 2015 Opera News excoriates Herheim for abandoning the traditional big ballet scene in Act 3 and scattering ballet dancing throughout the whole opera. This is, Dillon argues, "yet another example of the triumph of directorial ego over musical, dramatic, and historical sense." If you don't like Herheim's overlays on the sumptuous traditional production, spend your time elsewhere. I will not give this an A+ grade because I don't see this as a recording that every opera lover ought to have. But I enjoyed it enough to cheerfully give it an A.