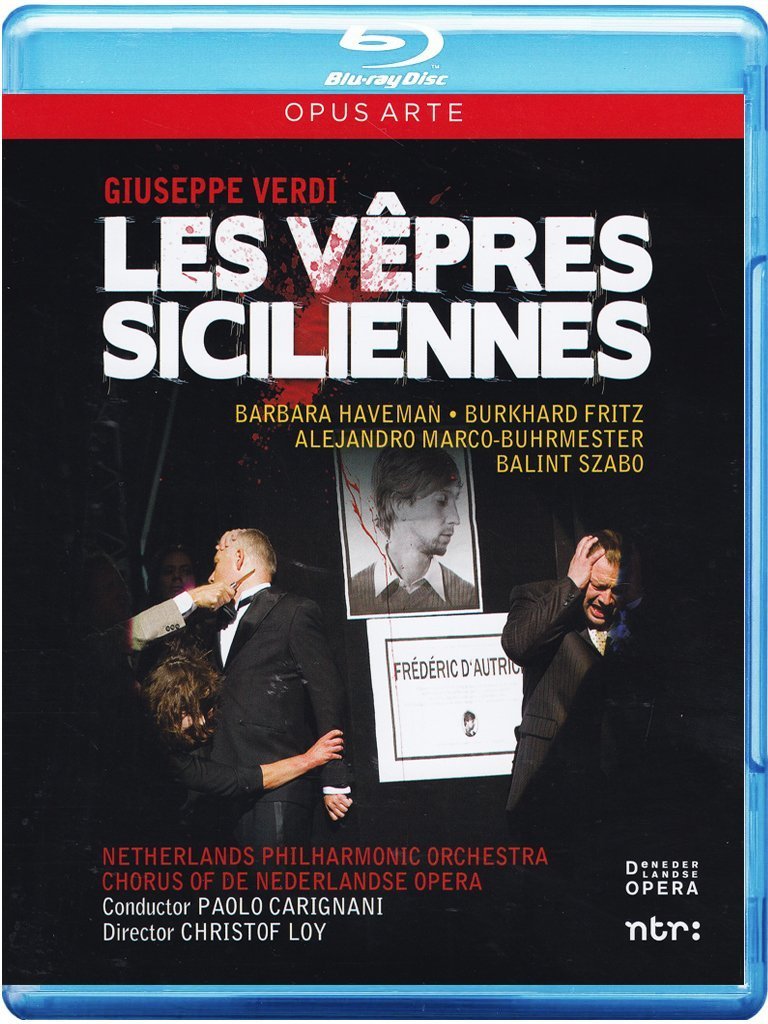

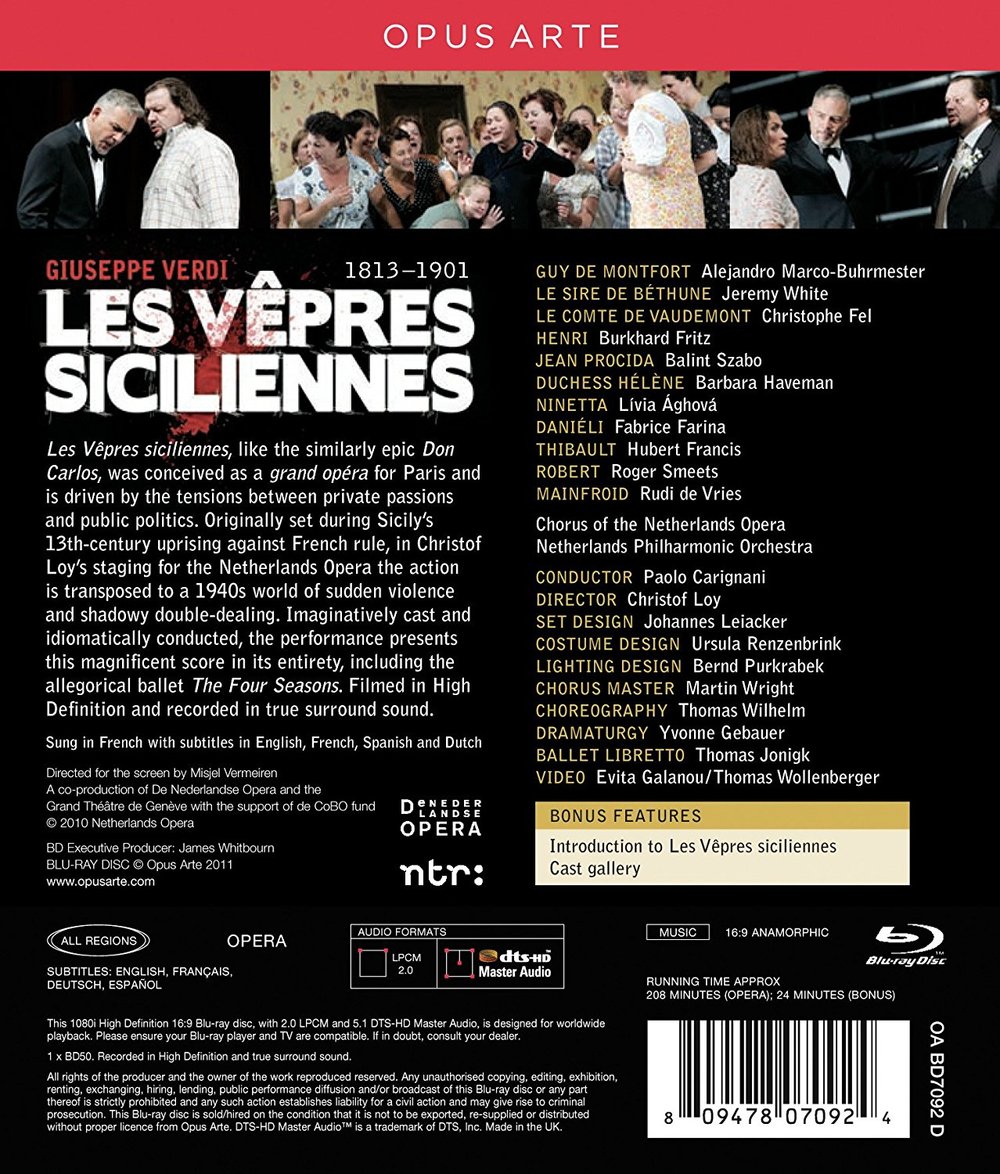

Verdi Les vêpres siciliennes opera to libretto by Charles Duveyrier and Eugène Scribe. Directed 2010 by Christof Loy at the Amsterdam Music Theatre. Stars Alejandro Marco-Buhrmester (Guy de Montfort), Jeremy White (La Sire de Béthune), Christophe Fel (Le Comte de Vaudemont), Burkhard Fritz (Henri), Balint Szabo (Jean Procida), Barbara Haveman (Duchess Hélène), Lívia Ághová (Ninetta), Fabrice Farina (Daniéli), Hubert Francis (Thibault), Roger Smeets (Robert), and Rudi de Vries (Mainfroid). Also features dancers Barbara Spitz (Barbara Nota), Adam Ster (Henri Nota), Richard Gittins (Frédéric d'Autriche), Katharina Wunderlich (Hélène d'Autriche), and Samon Presland (The Young Montfort) for the Four Seasons ballet segment. Paolo Carignani conducts the Netherlands Philharmonic Orchestra and the Koor van De Nederlandse Opera (Chorus Master Martin Wright). Ballet storybook by Thomas Jonigk; set design by Johannes Leiacker; costume design by Ursula Renzenbrink; lighting design by Bernd Purkrabek; choreography by Thomas Wilhelm; dramaturgy by Yvonne Gebauer; video by Evita Galanou and Thomas Wollenberger. Directed for TV by Misjel Vermeiren. Sung in French. Released 2011, disc has 5.1 dts-HD Master Audio sound. Grade: D+

Unless you are already an expert on Vêpres, please see first our review of the 2015 ROH Vêpres production. That story shows how well a properly-financed traditional production of this opera (with modest updating and overlays to cater to contemporary taste) can turn out. But what happens when a French grand opera meets a tight Dutch budget? You get a modern production where just about everything other than the singing and the orchestra is broken.

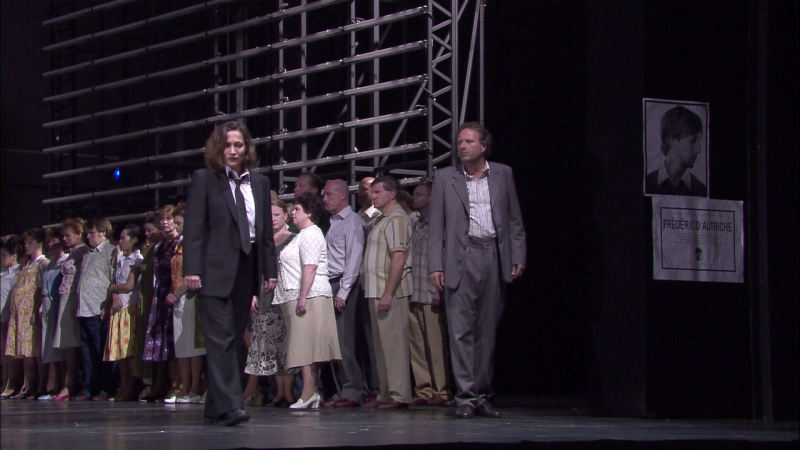

The biggest casting challenge in Vêpres is to find an older baritone and a younger tenor who can together make up a convincing father-and-son team. But, alas, if keeping costs down is major concern, you may wind up with pair like Alejandro Marco-Buhrmester playing the father Guy de Montfort and Burkhard Fritz playing the son Henri. Which man is the older? In fact, Alejandro is 6 calendar years older than Burkhard. But in physical terms, the trim Alejandro appears the same age or younger that the overweight Burkhard. And Burkhard doesn't look anything like a soldier/revolutionary who has just been released from prison—he looks like a computer programmer after 10 years of a diet of pizza and Pepsies:

Duchess Hélène, shown below, is played by the lean and sophisticated Barbara Haveman. She is way too slick to possibly find a love interest in blob Henri. Our tight budget doesn't allow for any costumes other than what's in the warehouse already or hanging in the closets of the chorus members at home. Below we see the peasant garb, which you find on any day in any Dutch grocery store. (I really don't know if management made the singers furnish their own costumes, but it sure looks that way.)

The aristocrats and French soldiers occupying Sicily wear slightly more refined costumes consisting of contemporary black and white. And since there's no money for sets either, it's smart to hire director Christof Loy, who is known for staging elaborate and exotic works (like, for example, Lulu) on empty, vast, dark stages. Since Vêpres has a double chorus, you can't just let all those folks stand around on the stage for 3 hours. Solution: get aggressive by putting 45 or so chairs on the stage so some of the singers can sit in various formations. In the screenshot below, the French occupation forces sit in the front-row chairs while the Sicilian peasants stand behind. As soon as the chorus members start moving around, it's very hard to tell who is who:

With a problematic cast plus sets, costumes, and props of no interest, you have to do something to keep the audience awake. Why not try some unusual videos projections on the back wall? Everyone in the audience knows the famous overture. So Loy came up with the idea of moving the overture into the middle of Act 1 while showing a video. The video consists of mug shots that suggest that this Vêpres is set in the mid-20th century somewhere in a country occupied by the forces of a modern (French) secret-police state. Below is the first set of mug shots. In the middle of the top row we see Henri (full name Henri Nota) and Hélène (full name Hélène d'Autriche). To the left of Henri is his mother, Barbara Nota, who doesn't appear in the opera but will be a character in the ballet that is featured later in the opera. To the right of Hélène we see John Procida, the revolutionary leader, whom we will meet a bit later. On the lower row are three other revolutionary characters with supporting roles. On the far right is Frédéric d'Autriche, Hélène's brother, a revolutionary who was executed by Montfort before the opera begins. It's beyond me how the audience is supposed to absorb all this in real time:

Suddenly the video image of Henri expands:

And now the image blinks!

After a slow transition, we see the mug shots smiling:

And gradually it's revealed to us what the persons in the mugshots may have looked like as children! All this is pretty remarkable. I can't tell if it's done (1) by physical means such as blending in older photos of the actors (or other people) or (2) with digital means using computer software originally invented to help investigators use photographs to solve missing person cases. And it's also a bit difficult to see what all this has to do with our opera other than to suggest how dangerous the modern police state can be:

After the Overture is finished, we get back to the libretto with the return of Procida (Balint Szabo). Here he sings his patriotic aria "Palerma" while we see tacky slide show images of the town and Procida baby photos:

The love duet of Duchess Hélène and poor soldier Henri is not very convincing:

The awkwardness of Hélène and Henri is painfully apparent to us in video close-up. Here's how this looked to the audience on the vast, empty stage:

In order to incense the Sicilian men and to foment revolt, Procida encourages the occupation forces to abuse 12 brides at the marriage festival. It's gets pretty vicious and sadistic as the women are forced to strip and mutilate themselves by crawling across shards of broken glass. This goes, of course, way beyond what Verdi had in mind:

And Montfort slashes the throat of a girl he believes to be an agitator:

Now we have the recognition scene between the monstrous father and the dopey son. Time wise, we have jumped from 1282 to, say, 1950, and this opera has absolutely no connection to King Louis the XIV. But every opera house will have a Sun King costume in the warehouse, so now we see Montfort in 18th century dress. All you can do is laugh:

When this opera was first staged in Paris in 1855, local custom required a self-standing ballet be performed as part of the production. Verdi wrote The Four Seasons ballet music for this, which is normally cut in modern productions. But with so little going for this show otherwise, why not use the Verdi music and let Dutch choreographers put on a modern dance show? Henri has just learned that the vile man he long loathed is really his long-lost father. Why not let the ballet be a day-dream of Henri how all his problems might be resolved in a happy ending? So away we go with an actual, if silly and flimsy, set with Henri looking on:

At this point the audience would be totally lost without help as to who the dancers represent:

And the audience would be bored without some raunchy slapstick humor:

The ballet ends with Montfort, Henri's mother, Hélène, Henri, and Freddy all together in one happy family:

Unfortunately, we must now leave the mug shots and ballet behind and return to the opera. Even thought our heroes live in a modern police state, they have learned nothing about operational security or counter-intelligence. Each conspirator wears a red rose!

There are more conspirators than Frenchmen at the ball:

The execution of Procida begins with an excruciatingly slow injection:

But Henri saves the day by calling Montfort, "Father."

Now everybody is united and happy. Even the corpses of the brides join in the celebration:

But Hélène learns that Procida's rebellion will start when the wedding is performed and the church bells ring:

Hélène fears Henri will die in the rebellion. Solution: cancel the wedding so there will be no ringing of bells. Her excuse for calling off the wedding seems rather strange for a bride in 1950:

I've spent enough time showing how Loy failed to translate Verdi's high-drama opera into a believable contemporary political thriller. Further, Loy's uneven conceptions and personal directing of the cast are clumsy and even sometimes amateurish. But I should also say that there is some fine solo and ensemble singing in this show that your ears can enjoy even while you have trouble believing your eyes. The orchestra plays well under Paolo Carignani, and recorded sound is acceptable. PQ is decent even though I think one SD camera was used for some of the whole-stage shots. Picture content is good with a mix of long-range, near-range, near, and close-up shots.

Now for a grade. The ROH Vêpres (released 2015) completely overshadows subject title and would be the obvious first choice. It would take a strong special reason for one to spend money and time on this Loy concoction. I thereof give this a D grade with a + for pleasant singing by most of the stars and the chorus.

Here's a clip that shows quite well the caliber of this production:

OR