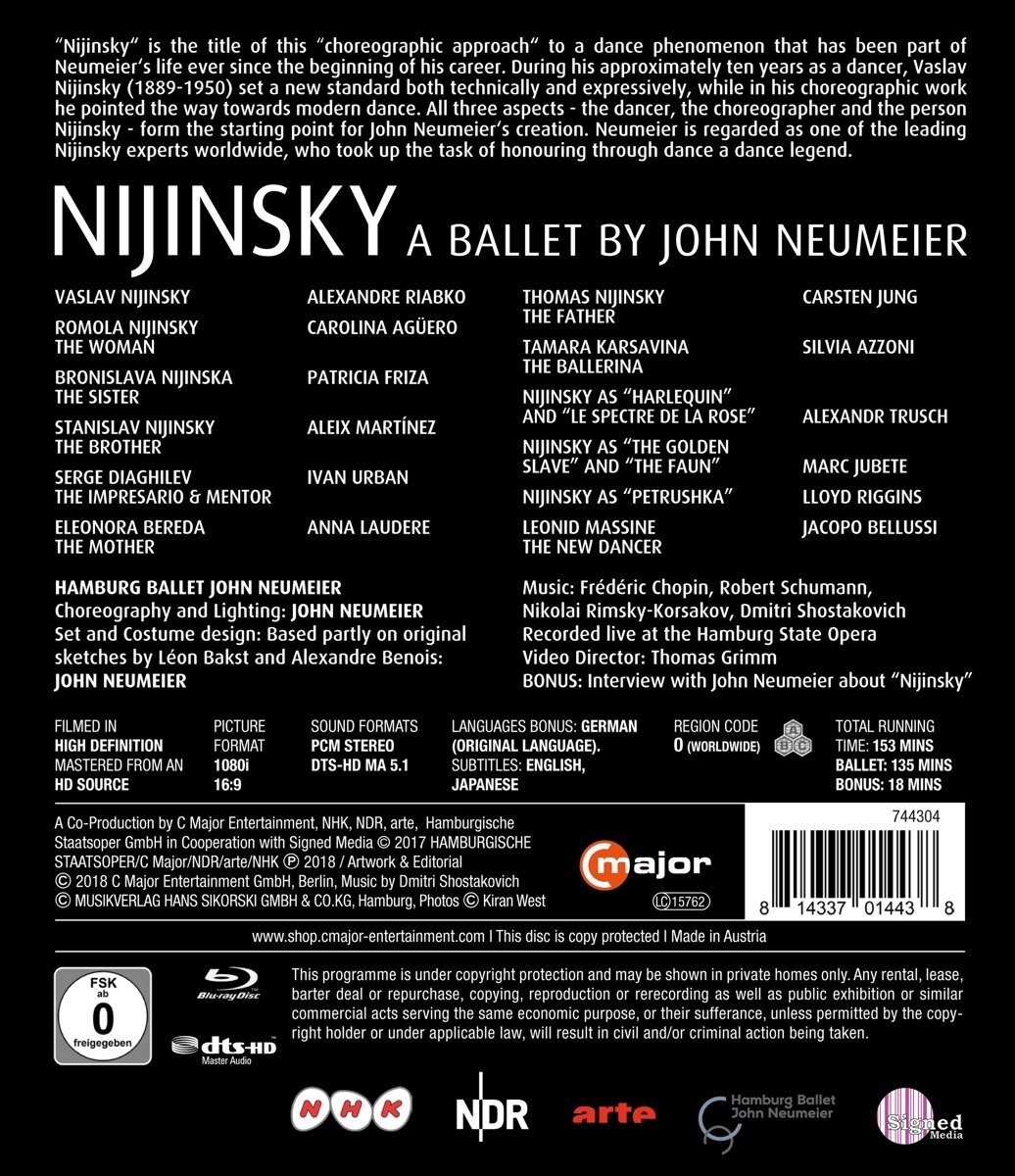

Nijinsky ballet. Choreographed by John Neumeier. Music by Frédéric Chopin, Robert Schumann, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, and Dmitri Shostakovich. Staged 2017 at the Hamburg State Opera. Stars Alexandre Riabko (Vaslav Nijinsky), Carolina Agüero (Romola Nijinsky/The Woman), Patricia Friza (Bronislava Nijinska/The Sister), Aleix Martínez (Stanislav Nijinsky/The Brother), Ivan Urban (Serge Diaghilev/The Impresario & Mentor), Anna Laudere (Eleonora Bereda/The Mother), Carsten Jung (Thomas Nijinsky/The Father), Silvia Azzoni (Tamara Karsavina/The Ballerina), Alexandr Trusch (Nijinsky as "Harlequin" and "Le Spectre de la Rose"), Marc Jubete (Nijinsky as "The Golden Slave" and "The Faun"), Lloyd Riggins (Nijinsky as "Petrushka"), and Jacopo Bellussi (Leonid Massine/The New Dancer). Lighting by John Neumeier; set and costume design by John Neumeier partly based on original sketches by Léon Bakst and Alexandre Benois. Directed for TV by Thomas Grimm. Released 2018, disc has 5.1 dts-HD Master Audio sound. Grade: B

Neumeier is a world-class authority on the person and life of Vaslav Nijinsky. In one of the bonus extras you see part of Neumeier’s exquisite collection of Nijinsky artifacts. Nijinsky is not a new ballet. It premiered in 2000, has been in the Hamburg repertoire ever since, and has also been produced by other ballet companies around the world. So ballet fans have probably been thirsting for a long time for a video of this. But be warned: it’s an extraordinarily complicated, rich, and challenging work to follow and to grasp.

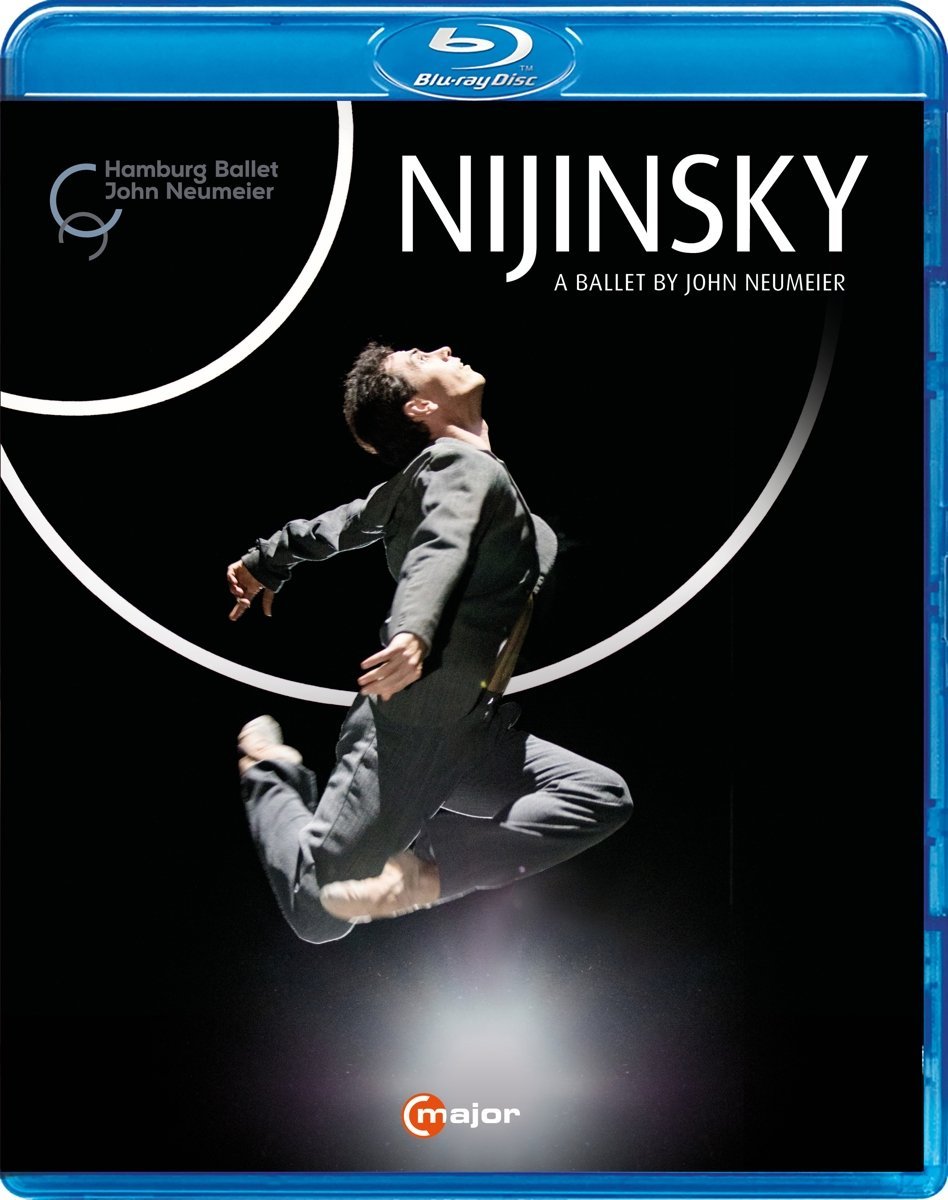

Since as early as 2004, Alexandre Riabko has been playing the role of Nijinsky as seen in the screenshot below. This view shows Riabko in Nijinsky’s last public performance, which he called his “Wedding with God.” The rest of the ballet is a long series of scenes (in 2 acts) that pass through the dancer’s mind as he finishes this performance. Act 1 tells the story Nijinsky’s career; Act 2 goes over the same ground again, but it is quite different as it consists of a study of the dancer’s soul. (After the Wedding with God, Nijinsky spent most of the rest of his life as a mental illness patient.)

Nijinsky was a very singular individual, but he was also a family man. Both his parents were dancers as were his brother and sister—all of them have important roles in the ballet. It seems Nijinsky was fundamentally heterosexual, but he took homosexual lovers who could help him build his career. His most important lover was Serge Diaghilev, the famous impresario shown as the center figure below being played by Ivan Urban. (On the left is Jacopo Bullissi playing the role of Leonid Massine, another prominent dancer):

From here on, we will refer to Nijinsky by his first name of Vaslav. Next below is Aleix Martínez as Stanislav Nijinsky, Vaslav’s brother, who went mad as a young man:

And here is Patricia Friza playing Vaslev’s sister, Bronislava Nijinsky. Bronislava would go on to have the most happy career of the family:

Next below is a real-life photo of sister Bronislava at 80 and still at work! We copied this image from one of our favorite pubs we subscribe to, the wonderful Dance Magazine out of New York. In each issue DM publishes a treasure from their archives—irresistible! Remembering that forgiveness is much easier to get than permission, we now thank DM again for hanging on to precious stuff like this:

Most of the screenshots in this review are near-views or close-ups following the style of videographer Grimm and Neumeier. But next below is a whole-stage view. We think the big illuminated hoops are actually a symbol of The Hamburg Ballet that have little or nothing to do with Vaslav:

Brother Stanislav’s madness:

Next below is the great character dancer Lloyd Riggins as Vaslav’s famous “Petrushka” persona:

And here behind Petrushka we see a “chorus line” with Vaslav, his sister, his father (Carsten Jung), and his mother, Eleonara Bereda (Anna Laudere). We told you this was a family drama:

Another famous Vaslav character was the “Spirit of the Rose”, here played by Alexander Trusch:

And here’s Vaslav’s famous Golden Slave persona danced by Marc Jubete:

And now we meet Romola Nijinsky (Carolina Agüero), Vaslav’s wife. Remember, this was at a time when the career of professional male dancer hardly existed: Vaslav’s work and fame was mostly based on the Ballets Russes and other promotions dreamed by impresario Diaghilev. Romola had money and she tracked Vaslav down because she was enamored of this fame. After a courtship of about 2 weeks, they married, which resulted in the end of Vaslav’s relationship with Diaghilev. Vaslav thought he could (with Romola’s help) start his own company. Well, Vaslav was a preternaturally great artist, but he had poor people skills and no flair for business management. He was not able to make it without Diaghilev. So the great dancer gave up his career for Romola and a family life! The marriage had it’s problems. And Vaslav eventually followed his brother into mental illness. But Romola stayed on to become his widow and thereafter did her best to promote his images and fame into the future:

Neumeier tells the bare bones of the true family story, but most of Neumeier’s choreography deals with the symbolic and psychological aspects of Vaslav’s tortured life. An example of this is the image below of Vaslav, Romola, and Vaslav’s alter ego, the Golden Slave, in a bizarre pas de deux morphed into a ménage à trois:

Vaslav was also a ground-breaking choreographer. People forget he created the dancing seen at the famous riotous premiere of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring. Some astute historians insist that the controversy at the Théâtre de Champs-Elysées was not over the music but about the dancing created by Vaslav. This event is portrayed by Neumeir as seen in two screenshots below with the virgin being consumed by soldiers fighting in World War I:

Romola’s devotion to Vaslav:

And the end of Nijinsky’s final dance we see a vast portrayal of the destruction of Europe in the Great War:

You will have to watch this title several (more likely many) times before you can hope to wrap your mind around all of Neimeier’s statements. The video content is also challenging and controversial. We did separate Wonk Worksheets on Act 1 and on Act 2. Together, we count exactly 1600 clips in 128 minutes of dancing. This cranks out to an average pace of less than 5 seconds per clip, and fewer than 45% of the clips show the whole bodies of dancers. This we believe is by far the most aggressive and atomizing video ever made of a Blu-ray ballet title. Neumeier and Grimm believe this movie-like filming of the ballet will be exiting and enticing to video viewers. But as you may know from reading our comments on video content, we fear the opposite. We believe such a pace and presentation is an assault on the senses that too quickly wears down the viewers’ ability to comfortably track, absorb, and enjoy what is happening.

The flip side of a too fast-paced video is the use of a blizzard of close-ups. This Nijinsky has the most extreme use of close-ups that we can remember seeing. We count 96 close-ups on the disc. We believe this number of close-ups takes us too far away from the idea of watching a ballet on a stage. Next below are 3 examples the kind of close-ups we wonder about:

Now for a grade. Artistic content, PQ, lighting, costumes, and sets are A or A+ quality. The music is engaging and entirely appropriate. The live piano music is fine. But the use of records for the symphonic music distracts and results in uneven SQ. These issues take us from A+ to the (lowest possible) A-. Next we would reduce the grade to C on account of the images coming at us like rounds from a quad-50 machine gun. But we will ratchet this up to a B on account of the originality of Neumeier’s book and the grand job it does in teaching us about the life of the great Nijinsky. Oh! We wish Neumeier/Grimm would watch some videos by Vincent Bataillon and give Bataillon’s approach a try on one of Neumeier’s yet unrecorded works!

Here’s an official clip from the Hamburg Ballet:

OR